Wednesday, February 24th, 2016

Kehinde Wiley and William Morris

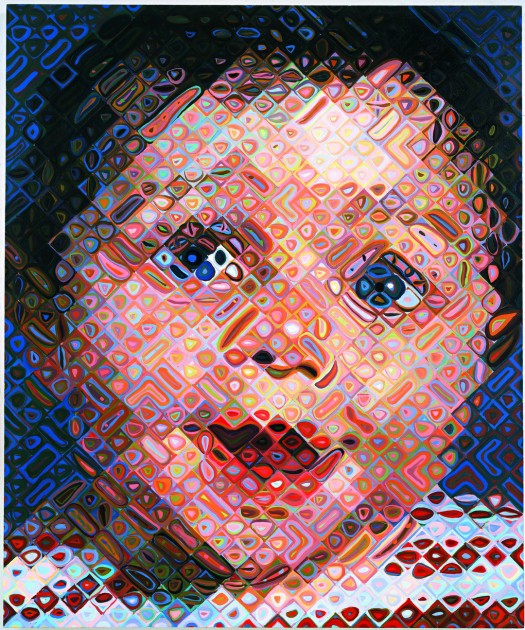

My different art experiences are colliding this week in an unusual way. This past weekend I went and saw the exhibition Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic at the Seattle Art Museum. And then, just today I taught my students about some of the designs that appear in William Morris’s wallpaper. When I got home this afternoon, I began to think about how some of William Morris’s work is referenced in a few of Kehinde Wiley’s paintings that I saw on display.

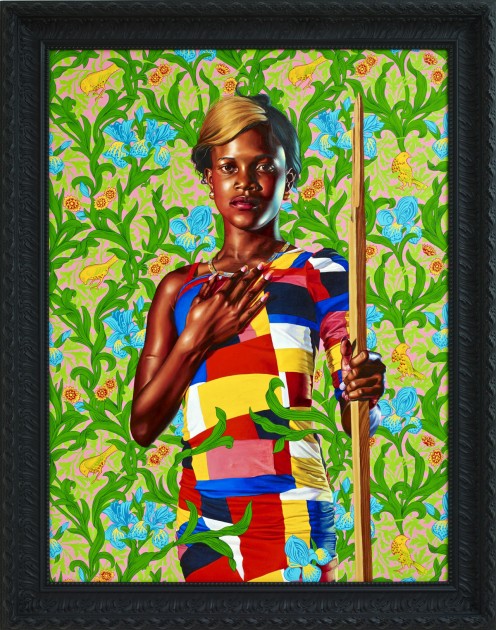

For example, the background design in Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness is clearly referencing a William Morris print of birds and irises. As someone who loves William Morris’s designs, I would have liked to have seen this references explored a little more clearly. A review of this same exhibition from last year (when it was at the Brooklyn Museum of Art) also suggested that mentioning the origins of the backgrounds in Wiley’s paintings would strengthen the show.

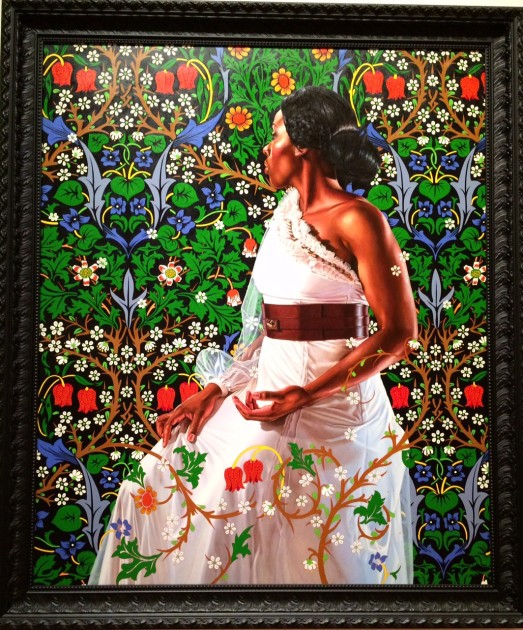

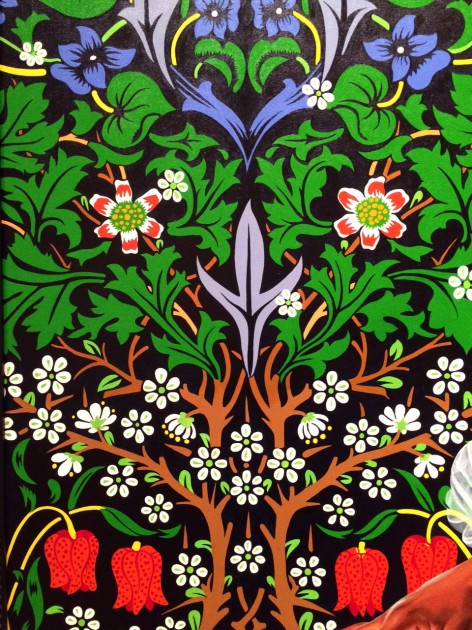

The reference to William Morris was most clearly pointed out to me in the portrait of Mrs. Siddons; the pattern is clearly inspired by the Blackthorn block-printed wallpaper that Morris designed in 1882.

It seems like there are several reasons for why Kehinde Wiley chooses to reference William Morris’s designs in some of his paintings. On one hand, Wiley’s compositions and designs are trying to draw awareness to the realm of history and art history, not only with the decorative motifs but the way the figure is represented (the female figure’s position which looks away from the viewer reminds me of depictions of the penitent Magdalene by George de la Tour).

In past centuries, fine art was typically associated with white Europeans and refinement. Wiley wants to challenge the idea that fine art and statements of cultural refinement are limited to a specific race; he does this by referencing European artistic traditions in his portraits of black people. To help emphasize his point, Wiley draws inspiration from Morris’s wallpaper designs, since they are associated with taste and the high-quality production surrounding the Arts & Crafts movement. In the exhibition catalog for this show, Annie Paul explains that Wiley creates “decorative backgrounds [which are] inspired by the English designer William Morris, who wove images from botany and zoology into intricate patterns signifying taste and discrimination.”1 It seems like Wiley occasionally uses Morris’s designs to reference English history and colonialism, too. For example, the inclusion of a Morris print in St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness (shown above) references the past colonial presence of the English in Jamaica.

So, Kehinde Wiley’s portraits of black figures, which contain visual references to European history and European art, call for attention and help to create a new vision of contemporary black identity and presence. Holland Cotter, in reviewing a 2005 exhibition of Wiley’s work, asserted as much by saying that Wiley “is a history painter. . . . By this I mean that he creates history as much as tells it.”2

And what would William Morris think about his imagery being utilized in this way? I think that he would be quite pleased: Morris was a socialist who wanted to bring about a change in the art world and society. William Morris felt like the arts, particularly the decorative arts, “were ‘sick’ as a consequence of the split between intellectual and mechanical work that occurred during the Renaissance.”3 Perhaps in a similar vein, Kehinde Wiley seeks to bind together racial divides and “heal” stereotypical assumptions about what constitutes art and portraiture.

So when Wiley’s paintings are considered in terms of social unity, Morris’s designs are very appropriate. Art historian Caroline Arscott has analyzed Morris’s designs in relation to the social climate of his day, finding that the designs “imagine an overcoming of social contradictions in an allegory performed ‘through the twists and turns of plants.’ In this way his aesthetic stands as a powerful equivalent for the recovered wholeness of men and women, of their relations to their fellows and to nature.”4 In many ways, Wiley is also suggesting similar themes of “wholeness” by binding different cultures together within his paintings. It isn’t surprising, then, that Wiley is inspired by designs of plants which repeatedly interconnect, wind, and bind themselves to each other.

1 Holland Cotter, “Art in Review: Kehinde Wiley,” New York Times, December 9, 2005.

2 Eugenie Tsai, ed., Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic (New York: Brooklyn Museum, 2015), 146.

3 Steve Edwards, “Victorian Britain: From Images of Modernity to the Modernity of Images,” in Art and Visual Culture 1850-2010 by Steve Edwards and Paul Wood, eds. (London: Tate Publishing 2012), p. 81.

4 Ibid., 81.