Monday, July 30th, 2012

Book Review: “Stealing Rembrandts” by Anthony M. Amore and Tom Mashberg

"Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists" by Anthony M. Amore and Tom Mashberg (2011)

This past weekend I finished reading the fairly new book, Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists. I thought that this book was an interesting and engaging way to discuss art crime, since it specifically revolved around heists of Rembrandt paintings and etchings. I thought that the approach to the book was well-balanced, too. Amore and Mashberg included tidbits of information about Rembrandt’s biography within their discussion of different crimes, which helped to vary the writing and information presented in the book. Without occasional tangents into Rembrandt’s life and works, I think that the presentation of crime scenes would have become too monotonous for the reader.

I thought that I would present just a few of the fun things that I learned from this book.

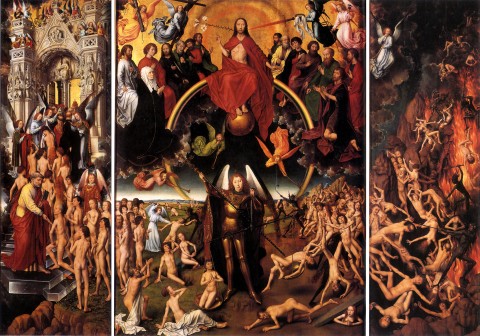

Rembrandt, Portrait of Jacob de Gheyn III (commonly called the "Takeaway Rembrandt"), 1632. Image courtesy Wikipedia

According to the Guinness Book of World Records, Rembrandt’s portrait of Jacob de Gehyn III is the most frequently stolen painting in history.1 (I think that this definition of “stolen” might need some more precise definition, especially when you consider works of art that were displaced or looted during times of war.2) Nonetheless, it is impressive to consider that this painting was stolen four times from the Dulwich Picture Gallery: in 1966, 1973, 1981 and 1983. Eight paintings were stolen in the 1966 heist, including Rembrandt’s A Girl at a Window (1645, see detail HERE). (Side note: Dulwich has had a difficult time with art thieves! In December 2011, a Barbara Hepworth sculpture was stolen from Dulwich Park, which is just a stone’s throw from the Dulwich Picture Gallery.)

One of the most amusing stories in Stealing Rembrandt revolves around the 1972 heist of the Worcester Art Museum. During this heist, several works of art were stolen, including Gauguin’s Brooding Woman. I was amused (and horrified) to read that Gauguin’s painting was placed on the car roof rack of the thieves’ getaway car; a man in the passenger seat stuck his right arm out of the window to hold the painting down during the escape!3 Gauguin’s subject doesn’t look too happy about her rough ride through the Worcester streets, does she?

I also learned something interesting about the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist of March 18, 1990. During the heist, for reasons known only to the thieves, a Rembrandt painting was removed from the walls and then abandoned. When officials came to the museum after the robbery, they noticed that Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait (1629) was sitting on the floor and leaning against a chest, with the back panel facing outward. Perhaps the oak panel was too heavy to carry, or perhaps the thieves forgot to carry it out. Either way, this painting was spared (although another Rembrandt painting, Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, was stolen during the heist). Given that none of the stolen Gardner paintings have been recovered yet, I feel like Rembrandt’s portrait deserves some special Harry Potter-esque nickname, like “The Painting That Lived” or “The Painting That Was Spared.”

Stealing Rembrandts also discussed some very interesting recovery stories for works of art. Titian’s “Rest on the Flight to Egypt” was stolen in an art heist in 1995 (from the Marquess of Bath’s estate in Longlead, England). The painting was recovered – of all things – in a plastic shopping bag at a bus stop.

I also was personally interested to know that a Rembrandt etching was stolen from a home in Sammamish, Washington in 2007. (I chuckled when I noticed that Sammamish was described as a “tiny Northwest village” in the book. That’s not quite true!) Stealing Rembrandts discusses the crime and the arrest of the individuals who were trying to sell the etching. However, I learned this evening that the book fails to mention one thing: although the owner identified the recovered frame, the owner believes that the recovered etching may be a fake.

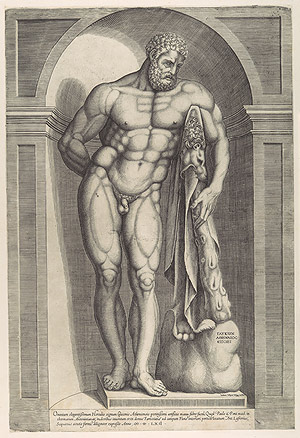

And finally, although this isn’t a recent crime, I wanted to include one last tidbit that I learned in Stealing Rembrandts. I didn’t know beforehand that Hans Memling’s “Last Judgment” triptych was stolen by pirates in the late 15th century (shortly after the triptych was completed). The painting was being shipped from Bruges, Belgium to Florence’s Medici Chapel. However, ever since the theft, the triptych has been located in Gdansk, Poland.4

Has anyone else read Stealing Rembrandts yet? Any other art crime books that you would recommend for my summer reading?

1Anthony M. Amore and Tom Mashberg, Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 67.

2 According to Noah Charney, the Ghent altarpiece claims the title of the most “coveted” work of art, having been involved in the highest number of thefts and crimes than any other work of art. To learn more about the Ghent altarpiece and crime, see Noah Charney’s book, “Stealing the Mystic Lamb.” Review and information are found HERE.

3 Amore and Mashberg, p. 43.

4 Ibid., 11.