Thursday, January 21st, 2016

Some Bernini Myths

Photograph of the Pantheon in the 19th century, with two towers created by Maderno and Borromini in the 17th century.

I have been thinking about a few myths surrounding the Baroque artist Bernini this evening. One prevalent myth is that Bernini created the two towers (nicknamed “ass’s ears”) that once decorated the top of the Pantheon. The towers were created in the seventeenth-century and were removed in 1892. Contrary to popular myth, a new publication on the Pantheon points out that Bernini wasn’t involved in the creation of these towers. Instead, the papal architect Maderno and his assistant Borromini were responsible for the towers. In some ways, it is ironic that these “ass’s ears” towers are attributed to Bernini instead of his rival Borromini! My guess is that Bernini may have been incorrectly identified with these Pantheon towers because of the two towers that he attempted to build at St. Peter’s Basilica, although that project was soon abandoned: not long after the first tower was built, it was demolished because it was unstable.

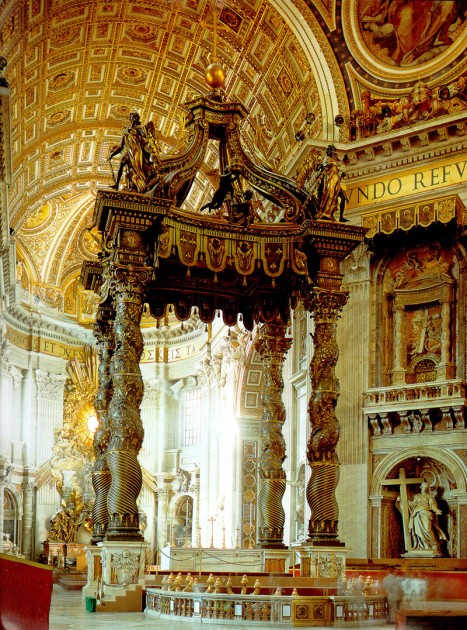

Another myth associated with Bernini and also the Pantheon has to do with the bronze that Bernini used for his Baldacchino at Saint Peter’s Basilica. We know that Urban VIII (a member of the Barberini family) removed bronze trusses from underneath the portico of the Pantheon in 1625. It has often been said that the bronze went to help create the Bernini’s baldacchino, which was created from 1624-1633. I remember learning about this in school, particularly in tandem with the saying, “quod non fecerunt Barbari fecerunt Barberini” (What the barbarians did not do, the Barberini did”). However, recent studies argue that the bronze from the Pantheon either did not go to St. Peter’s at all or was an extremely minuscule amount.1 Instead, the bronze from the Pantheon was used to create some of the cannons at Castel Sant’Angelo.

Bernini, detail of personification of Rio de la Plata from “Four Rivers Fountain,” 1651, Piazza Navona, Rome. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Another popular myth surrounding Bernini revolves around his Four Rivers Fountain (Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi) and Bernini’s rivalry with the architect Borromini. It has often been reported and joked that the figure of Rio de la Plata in the fountain has its arm raised, as if snubbing or shielding its gaze from Borromini’s church of Sant’Agnese, which is stands opposite the fountain. However, the building of this church was not until 1652, the year after this fountain was completed, so such a statement was not intended (but perhaps such meaning could have been perceived by either artist after-the-fact!).

Just this afternoon I came across information about the book Bernini and the Bell Towers: Architecture and Politics at the Vatican. The premise for this book is that Bernini’s failed attempt to build the towers at Saint Peters was not merely his own failure. I look forward to reading this book and deciding whether or not Bernini’s infamous failure with these towers has been misrepresented over the centuries.

Do you know of any other myths surrounding Bernini?

1 A few sources report that the bronze for the baldacchino came from Venice. For one citation, see here: https://books.google.com/books?id=CScdAQAAIAAJ&dq=bernini%20baldacchino%20venice%20bronze&pg=PA156#v=onepage&q&f=false