Wednesday, January 4th, 2017

Bing Crosby’s “Old West” and Countryside Art

I wrote in my previous post about how I was trying to learn more about Bing Crosby’s taste in art. I finally have figured out a few things about Bing and his personal art collection, namely that he liked works of art with Old West scenes and also scenes of the English countryside.

Bing Crosby also liked works of art by Alfred Munnings. A few years after his death in 1977, his wife auctioned off items from the Crosby estate, and even tried to sell the painting “On the Moor” by Munnings. However, the painting was withdrawn from the sale because it didn’t meet the minimum bid. Bing Crosby even showcased one of his paintings by Alfred Munnings in a 1954 interview with Edward R. Murrow on Person to Person. As the interview was about to conclude, Bing interrupts of the interviewer by asking saying that he wants to show something that “is really my pride and joy.” Bing continues:

Everyone has something in their home that they really like to go into rhapsodies about. This is a canvas by Sir Alfred Munnings, who was the head of the British Royal Academy for years. He’s considered the finest painter of the English country life and country scene. It represents the hunting scene and it recalls a very amusing story to me. Barney Dean, the late Barney Dean, the beloved gag writer who worked for us for so many years. We were having a party here. It was getting late-ish, four-ish or so. Just a few stragglers in the hall, two or three people, you know how they like to dawdle at a party, hate to say good night. Well, Barney was looking up at the picture for of ruminatively and I said, ‘Barney, what’s on your mind?’ Barney was from New York, Brooklyn, never left the pavement, never been off the bricks in his life, and he looked at the picture and said, ‘How come we never do this no more?’ (See 15:14-16:03 in clip below)

I can’t determine whether this painting is the “On the Moor” scene that went up for auction in 1982. The composition, however, is unusual for Munnings; he typically depicted his horses in profile view. This “head on” version is only seen in a few other paintings by Munnings, such as A Huntsman and Hounds (1906, shown below). This isn’t a work of art that was owned by Crosby, but the composition is a little similar (although Bing’s painting has more figures and is larger in scale):

Bing’s televised interview with Murrow was filmed from Bing Crosby’s home in Holmby Hills (Los Angeles). Although it is hard to see, at 15:16 Bing walks past another painting of a man riding a horse. I think that this might be a painting by Munnings, but it could also be a painting by Charles Russell (especially since library in Bing’s San Fransisco home was decorated with Charles Russell’s art). Either way, the subject matter isn’t surprising, due to Bing’s famous interest in horses and horse races.

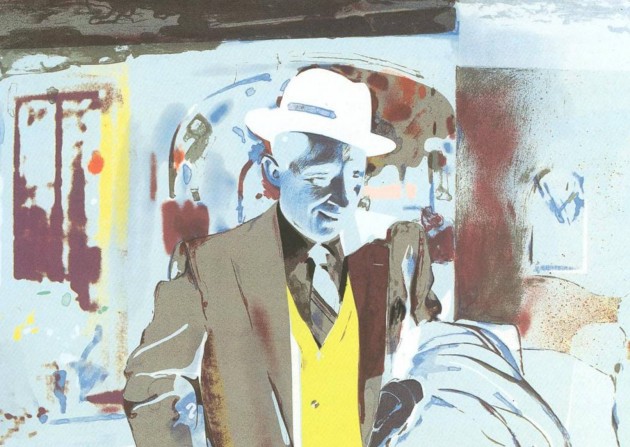

In a rather roundabout and ironic way, Bing Crosby and Alfred Munnings are also connected together through another artist: Richard Hamilton! In the mid-twentieth century, Hamilton was expelled from the Royal Academy by Alfred Munnings, who was an anti-modernist. Hamilton went on to become a successful pop artist, and even made a reverse-image screen print of Bing Crosby. The 1967 print capitalizes on Bing’s status as a pop culture icon through its title: I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas. It’s ironic that the artist who was expelled by Alfred Munnings ends up creating a modern work of art depicting a pop icon, and this pop icon is one who collects conservative paintings by Alfred Munnings! Whatever modernity Crosby may have represented as a pop culture icon, his personal taste in art appears to be much more traditional and conservative.