Wednesday, October 9th, 2019

Etruscan Forgeries: Inscriptions and the Penelli Sarcophagus

A few weeks ago I attended the Ridgway Lecture in archaeology at the University of Puget Sound. Dr. Richard Daniel De Puma spoke on Etruscan forgeries, which included a discussion of two authentic Etruscan sarcophagi and one fake sarcophagus.1 I really appreciated learning about this art from an archaeologist’s perspective, and also how archaeological finds and fakes prompted the interest in forgeries.

To start off, De Puma discussed one of the earliest documented Etruscan forgeries, which was made by Annio da Viterbo in the Renaissance. Annio da Viterbo was a Dominican friar and in 1493 he invited Pope Alexander VI to watch him excavate a site. Beforehand, da Viterbo planted an “Etruscan” tomb with five broken inscriptions, and he conveniently was able to “find” these inscriptions in front of the pope and deceptively suggest they were authentic. Da Viterbo began to “translate” such inscriptions, claiming that the text spoke of his hometown of Viterbo. If anyone had looked closely, though, they would have seen that the inscriptions were a jumble of Etruscan, Greek, Latin and hieroglyphs all mixed together.

According to Annio da Viterbo, the text included information about how the city of Viterbo was the center of the universe, how Noah’s ark actually had landed in Viterbo and not Mount Ararat, and how Noah was the first pope (not Peter!). Regardless of how ridiculous these claims seem today, da Viterbo’s findings were celebrated and he found himself promoted within the papal court. He also started to give public lectures and had immense influence on the thinking of educated Europeans in the 16th and 17th centuries.2 It took over one hundred years before his forgeries were proven as fakes.

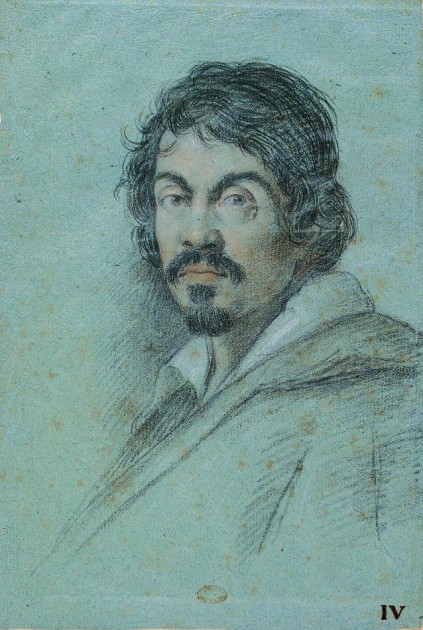

Edgar Degas, “Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery,” 1879-80. Soft-ground etching, drypoint, aquatint, and etching (Metropolitan Museum of Art). Image in public domain.

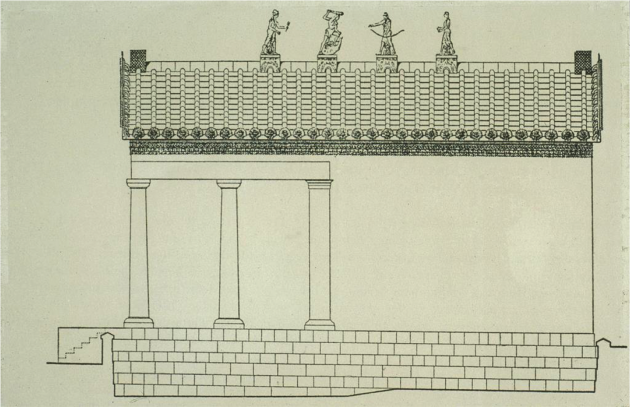

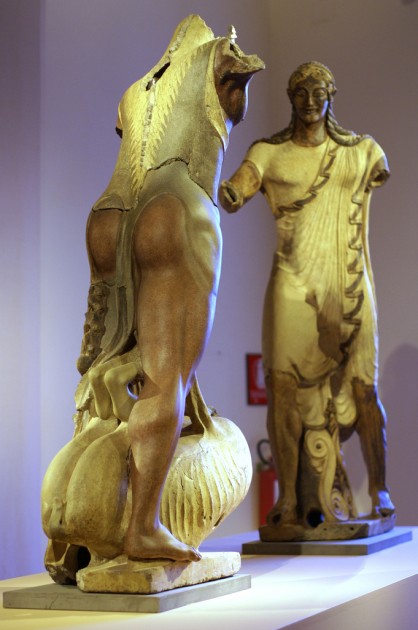

Another forgery in the Etruscan style is a sculpture, not just an inscription, and it was made in the 19th century. But the story begins with an authentic work of art: the Sarcophagus of the Spouses at Ceveteri, was excavated in the winter of 1845-46 and immediately drew attention. The sarcophagus, which was found in fragments, entered the Louvre collection in 1861 and was restored by Enrico Penelli. This sarcophagus was a prized addition to the Louvre collection, and Degas even included a depiction of Mary Cassatt looking at the sculpture in one of his prints (see above).

If this Louvre restorer, Enrico Penelli, had been an honest man, the story might have ended there. But Enrico, along with his brother Piero Penelli, decided to make a forged “Etruscan” sarcophagus that they claimed was excavated in Caere. This sarcophagus entered the collection of the British Museum in 1873.

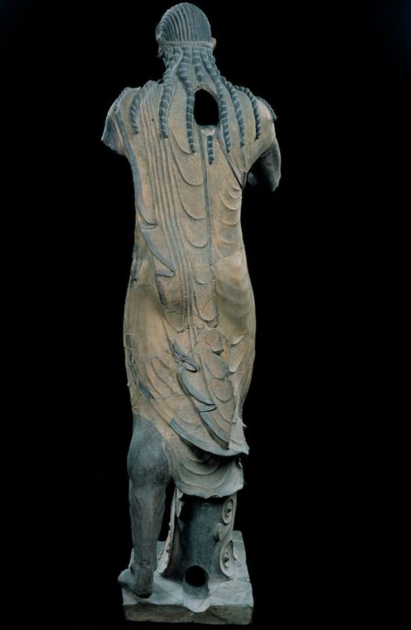

Penelli Sarcophagus, c. 1873 (forgery made to appear in the style of 550-525 BCE). British Museum. Image courtesy of British Museum via Creative Commons license

In their desire to have a sarcophagus that was somewhat similar in size and decoration to the one in the Louvre, the British seemed all too eager to accept this sarcophagus as authentic. However, a few decades later another authentic Etruscan sarcophagus (also called “Sarcophagus of the Spouses,”) was discovered at Ceveteri in 1898. This second find, which is now in the Etruscan National Museum in Rome, is very similar in composition and style to the Louvre sarcophagus. These striking similarities made it seemed more certain that the British Museum sarcophagus was a fake. However, it took more than sixty years for the British Museum to take it off of display, despite that the Enrico Penelli had confessed his misdeed to the archaeologist Solomon Reinach.

There are several things that suggest the Penelli Sarcophagus is not authentic: the man’s hair is cropped very short, which is different from the braided hair typically shown; the woman is wearing clothing that looks like nineteenth-century undergarments; the man is nude; the poses (including the propped up knee) are unlike Etruscan examples. There even is an inscription included that was directly copied off of a gold pin from the Louvre, so the dedicatory inscription about a fibula doesn’t make sense in the context of a sarcophagus.3 Even the sphinx-like sirens at the feet are unusual for an Etruscan sarcophagus, and the frieze underneath reminds me more of Greek imagery on vases and relief carvings.

The British Museum has now accepted the “fake” status of this sarcophagus, and even brought it back out on display. Dr. De Puma said that he remembered that the British Museum put the sarcophagus on display in a show dedicated to fakes from all kinds of periods, and I believe he was referring to the 1961 exhibition “Forgeries and Deceptive Copies.” Do you wish that this sculpture was back on display? It is pretty terrible aesthetically, I think, but its history is interesting!

1 Dr. Richard Daniel De Puma, “Etruscan Forgeries.” Lecture, The Ridgeway Lecture 2019-2020 from University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, WA, September 28, 2019.

2 Walter Stevens, “When Pope Noah Ruled the Etruscans: Annius of Viterbo and His Forged “Antiquities,” MLN 119, no. 1 (2004): S201-223. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.seattleu.edu/stable/3251832.

3 The inscription says “I am the fibula of Arathia Velasvna and Tursikina gave me [to Arathia].”