Tuesday, August 25th, 2015

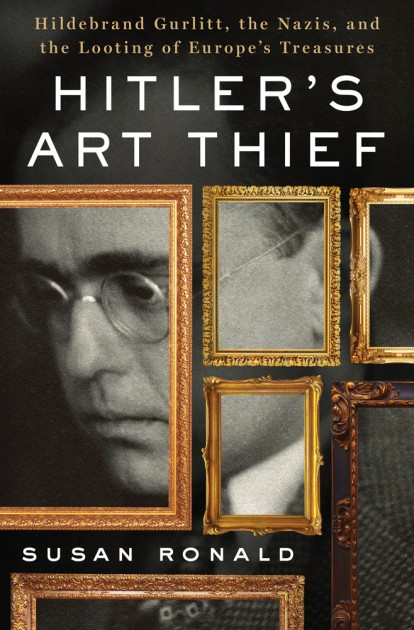

Book Review and Giveaway: “Hitler’s Art Thief”

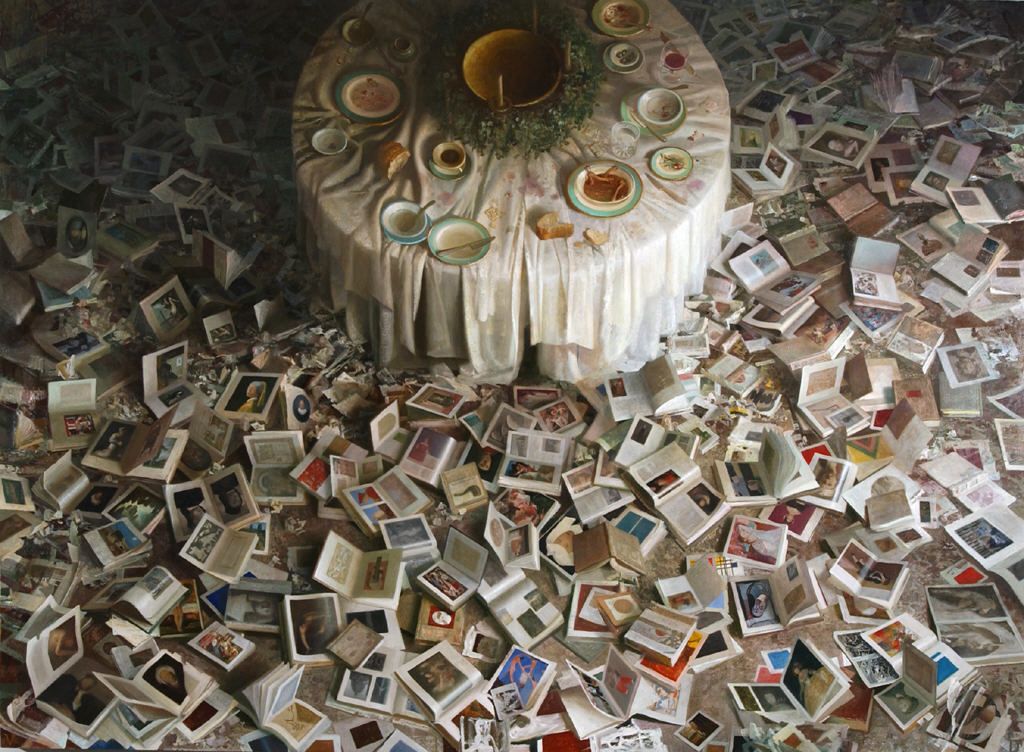

I feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to read an advance proof copy of Susan Ronald’s forthcoming book, Hitler’s Art Thief: Hildebrand Gurlitt, the Nazis and the Looting of Europe’s Treasures. This book is slated to be published next month, on September 22, 2015. Ronald recounts and pieces together the story of Cornelius Gurlitt, a recluse who received a lot of media attention when over a thousand works of art were discovered in his Munich apartment in November 2013.1 Much of Cornelius’ collection was inherited from his father Hildebrand; the latter was an art dealer during the Nazi era who built his personal collection from the spoliation of museums and Jewish family estates. Susan Ronald’s book primarily is dedicated to telling the biography of Hildebrand, while simultaneously building up a broader context to explain the political and socio-cultural situation in Germany during WWI and WWII.

As an art historian, I felt like the latter third of the book (about the last one hundred pages or so) was especially interesting to me. This part of the book discusses underhanded ways in which Hildebrand Gurlitt amassed his collection, which included one twisted state of events that enabled Gurlitt to not even pay for any of the paintings he claimed at an auction of the Georges Viau collection in 1942!2 More than anything, though, I wanted to learn more about the stories behind some of the paintings which were stolen. Although Ronald focuses mostly on historical events regarding Hildebrand Gurlitt and his son Cornelius, there were snippets of information on paintings that I particularly enjoyed in this book.

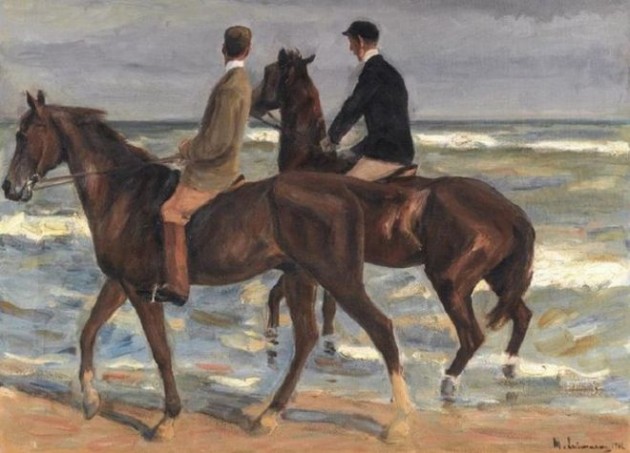

Ronald mentions Max Liebermann’s Two Riders on a Beach a few times in her book. This painting had been taken from the David Friedmann collection by Hildebrand Gurlitt. When authorities stormed Cornelius Gurlitt’s flat in 2013, they took this painting off of the wall, where it had hung for over four decades!3 Clearly, the Gurlitt family was proud of this purloined piece. Before that point, Cornelius’ father Hildebrand had hung this painting on his living-room wall in Dresden.4 The painting was returned to David Friedmann’s family. Two Riders on a Beach, was the first of the Gurlitt hoard to go to auction, was sold by Sotheby’s earlier this year in June.

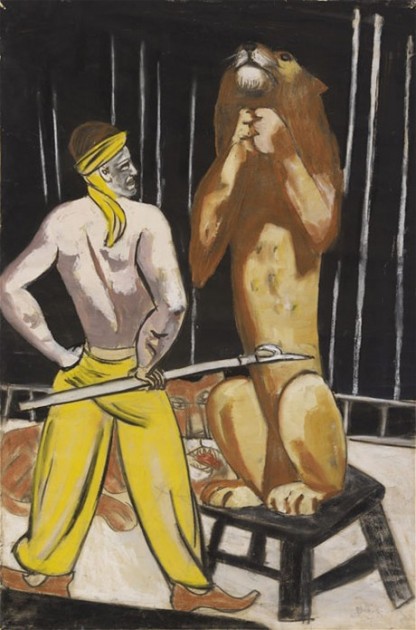

Beckmann’s The Lion Tamer is actually the piece which helped lead authorities closer to Cornelius and his collection. Cornelius put this piece up for auction at the Lempertz auction house in 2011. Ronald speculates that Cornelius may have opted to use this major auction house in order to get money quickly, perhaps to help pay his sister’s medical bills for her cancer treatments.4 When this painting went on the market, this major German auction house was contacted by layers who represented the family of Alfred Flechtheim, who had originally owned the painting during the Nazi era. Under pressure from these lawyers, Cornelius (who was the unnamed client selling the painting) agreed to split the proceeds with the heirs of the Flechtheim family. The Fletchtheim heirs felt that this action helped to at least acknowledge the wrongdoing which took place during the Nazi era, although I wish that they could have received all of the proceeds!5

Susan Ronald also writes a few times about Matisse’s Seated Woman. I liked learning about this painting, which originally belonged to the Jewish art dealer David Rosenberg, since I recently wrote about another Matisse painting that was once owned by David Rosenberg. Unforunately, Seated Woman is still under controversy: despite the apparent fact that Hildebrand Gurlitt took this painting, there isn’t a concrete trail of evidence to pinpoint how Gurlitt came into possession of the painting. However, luckily, it is agreed that the painting did belong to the Rosenbergs. Although it has been announced that the Matisse painting will be returned, it is uncertain when the transfer will actually take place, due to this legal limbo.6

I think that Hitler’s Art Thief is a good book for history buffs and also for those who want a basic introduction to the art looting which took place during the Nazi era. Even as a seasoned art historian (who has read dozens of books and articles on Nazi looting), I learned new things too! And I’m pleased to announce that, through the generosity of St. Martin’s Press, one lucky winner will be able to receive a free copy of this book!

Be among the first to read this new publication by entering this giveaway! I will be randomly selecting one winner (using this site) on September 21, 2015. You can enter your name up to three times. Here are the ways you can enter:

1) Leave a comment on this post!

2) Tweet about the giveaway (be sure to include my Twitter name: @albertis_window in your tweet, so I can find it).

3) Write about this giveaway on your own blog or website, and then include the URL in a comment on this post.

Thanks to St. Martin’s Press for generously providing an advance review copy and giveaway copy of Hitler’s Art Thief.

1 Cornelius Gurlitt, who died in May 2014, bequeathed his collection to the Bern Art Museum in Switzerland. This action prompted outcry from Jewish groups, and the Bern museum is working to ensure that no looted art appears on Swiss soil.

2 Susan Ronald, Hitler’s Art Thief: Hildebrand Gurlitt, the Nazis and the Looting of Europe’s Treasures (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015), 226-229.

3 Ibid., 315.

4 Ibid., 313.

5 Ibid., 312.

6 Ibid., 319.