Monday, December 7th, 2009

Vasari and Female Artists

I’m in a state of shock. Vasari is best known as the biographer for the great (male) artists of the Italian Renaissance – Michelangelo, Donatello, Raphael, Leonardo, etc. But did you know that Vasari mentioned four females in his Lives of the Artists? I had no idea, until I discovered Vasari’s chapter on Properzia de’Rossi the other night. I seriously was dumbfounded – I stared at the word “sculptress” for at least ten seconds.

But don’t get too excited, my feminist art historian friends. Vasari only mentions Rossi in a few paragraphs, and then taps on a few short sentences about three other female artists: Sister Plautilla, Madonna Lucrezia, and Sofonisba Anguissola. You’ve never heard of these artists, you say? Let me show you a sampling of their work:

On the right is Properzia de’Rossi’s Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife (1520s). Vasari mentions that the subject matter of this panel can parallel the unrequited love that Rossi experienced in her own life. I think this comparison is telling about Vasari’s views on women and feminine nature. The editor of my Lives edition also echoed my thoughts, saying that “while male artists execute works without regard to their personal feelings throughout the Lives, Vasari seems unable to imagine a woman creating a work of art without sentimental or romantic inspiration.”1

On the right is Properzia de’Rossi’s Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife (1520s). Vasari mentions that the subject matter of this panel can parallel the unrequited love that Rossi experienced in her own life. I think this comparison is telling about Vasari’s views on women and feminine nature. The editor of my Lives edition also echoed my thoughts, saying that “while male artists execute works without regard to their personal feelings throughout the Lives, Vasari seems unable to imagine a woman creating a work of art without sentimental or romantic inspiration.”1

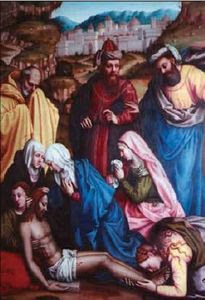

On the left is Lamentation with Saints (16th century) by Sister Plautilla (Plautilla Nelli). Vasari mentions that Plautilla was an extremely prolific painter, but surprisingly (or perhaps not-so-surprisingly), only three works are definitively attributed to her today. In an effort to bring public awareness to this artist, the Florence Committee of National Museum Women in the Arts paid to have Lamentation restored in 2006 (see news article here).

On the left is Lamentation with Saints (16th century) by Sister Plautilla (Plautilla Nelli). Vasari mentions that Plautilla was an extremely prolific painter, but surprisingly (or perhaps not-so-surprisingly), only three works are definitively attributed to her today. In an effort to bring public awareness to this artist, the Florence Committee of National Museum Women in the Arts paid to have Lamentation restored in 2006 (see news article here).

I think it’s especially interesting that Vasari doesn’t make any statements about Plautilla’s divine role as an artist or God-given talent (which he makes about the male artists in his book). Instead, he stresses that Plautilla and the other ]female artists learned and acquired artistic skill. Futhermore, Vasari wrote this about Plautilla: “But best among her works are those she imitated from others, which demonstrates that she would have created marvellous works if, like men, she had been able to study and work on design and draw natural objects from life.”2 Plautilla was alive when Vasari wrote her biography, and I wonder if she cringed to know that Vasari thought her best works were those that she copied from the divinely inspired, male artists.

Sofonisba Anguissola is the only female artist with whom I was familiar before reading Vasari. I read about Anguissola when I was doing research on Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard. Several scholars think that Caravaggio’s two versions of this subject were influenced by Anguissola’s Boy Bitten by a Crayfish (also called Boy Bitten by a Crab, c. 1554, on right). Mary Garrard has discussed Anguissola’s drawing in depth. She mentioned how Anguissola painted a picture of a laughing girls, which Michelangelo saw and commented that “the image of a crying boy would have been better.”3 Garrard finds that Michelangelo’s statement implied that boys are better artistic subjects than girls, and tragedy is better than comedy.4 Upon hearing this, Anguissola sent Michelangelo the drawing of Boy Bitten by a Crayfish. However, instead of showing the crying male in a tragic, noble position (and follow Michelangelo’s inferred suggestion), Anguissola shows the boy in an ignoble state with an amused female standing nearby. Wasn’t Anguissola a little sassy? I wonder what Michelangelo thought of the drawing.

Sofonisba Anguissola is the only female artist with whom I was familiar before reading Vasari. I read about Anguissola when I was doing research on Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard. Several scholars think that Caravaggio’s two versions of this subject were influenced by Anguissola’s Boy Bitten by a Crayfish (also called Boy Bitten by a Crab, c. 1554, on right). Mary Garrard has discussed Anguissola’s drawing in depth. She mentioned how Anguissola painted a picture of a laughing girls, which Michelangelo saw and commented that “the image of a crying boy would have been better.”3 Garrard finds that Michelangelo’s statement implied that boys are better artistic subjects than girls, and tragedy is better than comedy.4 Upon hearing this, Anguissola sent Michelangelo the drawing of Boy Bitten by a Crayfish. However, instead of showing the crying male in a tragic, noble position (and follow Michelangelo’s inferred suggestion), Anguissola shows the boy in an ignoble state with an amused female standing nearby. Wasn’t Anguissola a little sassy? I wonder what Michelangelo thought of the drawing.

Madonna Lucrezia is the other female artist mentioned by Vasari. Unfortunately, there isn’t any (known) surviving art by her. In fact, we know little about Lucrezia beyond that she was active around 1560 and her teacher was Alessandro Allori. It’s sad to think that her work and life is lost to history, most likely because she was a female. I’m glad that Vasari made the effort to mention her and these other females in his Lives, but also disappointed that most females didn’t receive artistic opportunity or art historical attention at the time. It makes me wonder what other female artists have been unappreciated and obscured by historical biases.

Is anyone else shocked that Vasari mentioned female artists in his text?

1 Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, translation by Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (London: Oxford University Press, 1991), 565.

2 Ibid., 342.

3 Mary D. Garrard, “Here’s Looking at Me: Sofonisba Anguissola and the Problem of the Woman Artist,” Renaissance Quarterly 47, no. 3 (Autumn, 1994): 611.

4 Ibid., 612.

To tell you the truth I was not shocked… but only because I have taught "women and art" and read a lot on the topic.

1) I have some bibliography listed on my website, below the student videos that were my seminar's final project.

(Start your reading here: http://www.arttrav.com/art-history-tools/female-artist-film/)

2) Not listed much here are the writers after Vasari who comment on female artists. The general attitude towards them is that they are "exceptions" for their sex, some kind of mutant!

3) Have you read this book (not just for female artists but for women IN art too)?: Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, eds. Geraldine A. Johnson and Sara F. Matthews Grieco (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Wow, the bibliography and student videos are a great resource, ak! Thanks for that link. I'm also very interested in that book by Johnson and Greico. Thanks for that recommendation. There is a similar book that I also want to read: "Italian Women Artists from Renaissance to Baroque" by Claudio Strinati. Has anyone read this book? Is it any good?

I have read a little about how women artists were considered to be exceptions for their sex. Isn't it ironic? Male artists were considered to be "geniuses," while female artists were considered to be freaks of nature.

Great post, M! I also heard about Sofonisba in my handy-dandy Stokstadt, but none of the others were even remotely familiar.

Vasari's quote about Sister Plautilla's art is interesting. Basically he's saying that if she's had the same opportunities to study and practice that men did, she would have been a great artist. Which makes me wonder if it ever occurred to him that maybe women like Plautilla should be given said opportunities. Probably not.

You're back! Hooray, hooray!

So, of course, I do not know who Vasari is, however, I LOVED reading about female artists! More, please!

And, of course, the screaming feminist in me rears her ugly head (or maybe its beautiful head!) especially when you mentioned that Vasari said that the skills were "learned and acquired"!

I, obviously, know very little about art, but my thoughts on it are that any artist in any medium — like any profession in the world — is born with an eye for what he/she is doing, but usually becomes truly wonderful at it through good training, education, experience, and mentoring. How interesting to think that some believe men just have the talent naturally while women only have it through education and imitation.

(And by interesting I mean how absurd!)

And finally, I think de'Rossi's panel is especially beautiful.

At the risk of sounding like a complete idiot I'll keep my comment to one sentence.

I think the word "sculptress" sounds rather racy, don't you?

Thanks for the comments, everyone!

Yeah, heidekind, I doubt it occurred to Vasari that women should have more opportunities in the art world. Sigh. At least he was comprehensive enough to include women, though. I am glad about that.

e, I also think it's totally absurd about acquired skill vs. natural talent. There is another thing that I think is ironic: it's quite obvious that Vasari felt like he was paying these women a great compliment by stressing their acquired skill. He ends this chapter on female artists with the hyperbolic-ish snippet from a piece of poetry:

"And truly women have excelled indeed

In every art to which they set their hand."

A compliment? Sure. But when one reads how much Vasari stresses how females acquire talent (instead of being born with divine talent), that little poem seems like a trite insult.

And YAY for your comment, Emperor of EUtopia! It made me chuckle. And yes, "sculptress" does sound quite racy. I'm glad it's not a very common word today. 🙂

At least Vasari mentioned another woman artist: Suor Antonia Doni, Paolo Uccello's daughter. This painting has been attributed to her (as well as to her father): http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Paolo_uccello,_tebaide.jpg

Thanks for your comment, sapphron (and welcome to my blog! I don't believe you have commented before). You are right: Antonia Uccello is mentioned by Vasari, although she isn't grouped with the other female artists (which is why I didn't think to post on her).

For those who are interested, Antonia is mentioned in Vasari's biography of Paolo Uccello. Antonia is briefly mentioned as a daughter "who knew how to draw." We also know that Antonia was a Carmelite nun.

I've tried to find out more information on Antonia, but it looks like there isn't much information about her. A footnote in Psychology and the Humanities mentions that Antonia "disappeared," but I'm not quite sure what is meant in that context. I suppose it might mean that she disappeared from history, since she is such an enigmatic figure.

I didn't realize that some have attributed "La Tebaide" to Antonia. How interesting!