Monday, June 4th, 2012

Three Favorite Quotes: Gombrich, Kandinsky, Ruskin

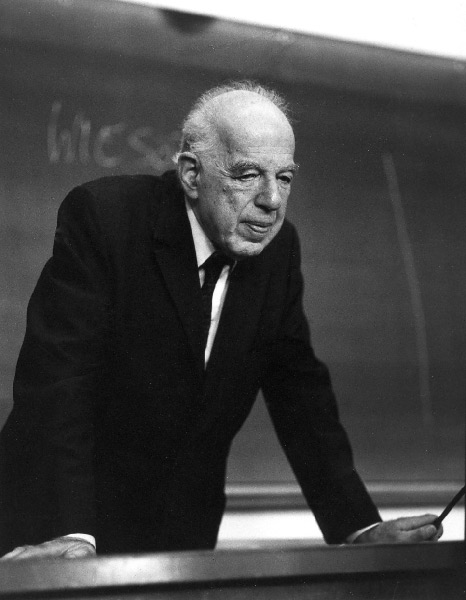

The end of the quarter is here. I taught my last lecture this morning. Per custom, I shared with my students my favorite quote about art. This quote is from Gombrich’s well-known art history text, The Story of Art. Gombrich discusses how one never stops learning about art and how works of art are inexhaustible. I have found these things to be true in my own experience and career. And personally, I find it exciting that there are always more things to learn about art. In fact, one of the reasons I love being a professor is that I am continually introduced to new perspectives and ideas about art by my students.

Anyhow, this evening I realized with dismay that I have never shared this quote by Gombrich on my blog! I’ve included it below, along with two other quotes that I love.

“One never finishes learning about art. There are always new things to discover. Great works of art seem to look different every time one stands before them. They seem to be as inexhaustible and unpredictable as real human beings.” – E. H. Gombrich, The Story of Art

“Color directly influences the soul. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another purposively, to cause vibrations in the soul.” – Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art1

A colored engraving of John Ruskin, from "The Poetry of Architecture" publication, 1838. Image courtesy Wikipedia

“The purest and most thoughtful minds are those which love color the most.” – John Ruskin

What about you? What are your favorite quotes about art? Why?

1 Wassily Kandinsky, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art.” 1911. Another variation of above translation is available online (accessed 3 June 2012): http://books.google.com/books?id=0AV8LSrexjYC&pg=PA32&lpg=PA32&dq=Color+directly+influences+the+soul.+Color+is+the+keyboard&source=bl&ots=Rb-XcPx8ls&sig=VEyjcyqvopygZwAuZKcf0pNLlPA&hl=en&sa=X&ei=14XNT7zMHMGU2AXtp7XiAg&ved=0CFoQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q&f=false