Thursday, March 26th, 2009

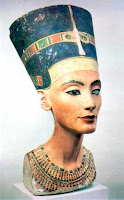

I never thought I would be interested in reading an article in my father-in-law’s Radiology magazine. However, I was intrigued that the cover of their recent issue has a picture of the famous Nefertiti statue bust (made by the artist Thutmose, Dynasty XVIII (ca. 1353-1335 BC)). Recently, some computed tomography (CT) performed on the core and surface of the statue bust has revealed new information.

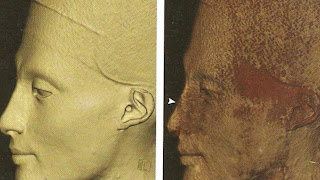

According to this article, there are slightly different physical characteristics which appear on the inner core of the statue (consequently revealing a “second hidden face”).1 On the inner core, the CT revealed that there “creases around the corners of the mouth and cheeks, a less harmonious nose ridge, and less prominent cheekbones. The nose [also] showed a slight bump.”2

The visible outer layer (left) and the inner layer (right) show a difference in the nose (the bump is indicated by an arrow)

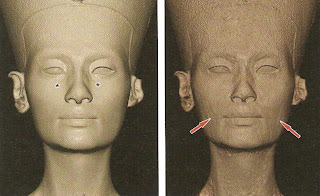

Although the outer surface of stucco refined and softened these wrinkles and bumps, it is also interesting that there is a more pronounced shaping of the eyelid corners on the outer layer (see image below). This emphasis on the outer eyes supports interpretations that this bust was supposed to be recognized as a depiction of a mature woman, not of a woman of flawless beauty.”4

The shaping of the eyelid corners on the outer (visible) surface can be seen on the right (indicated by *). On the inner core (left) creases in the corners of the mouth (arrows) were found.

The shaping of the eyelid corners on the outer (visible) surface can be seen on the right (indicated by *). On the inner core (left) creases in the corners of the mouth (arrows) were found.I think it’s fascinating to look at different facial characteristics on the inner core – perhaps the inner core is a more correct representation of how Nefertiti appeared in life. It’s great that technology can help historians and archaeologists learn more about art. In this study, CT also showed more information regarding the types of tools and materials that were used to sculpt the bust. In addition, further details were revealed about the thickness of the stucco, which will serve as useful information for conservators.

Although I didn’t understand all of the scientific terminology or system of measurement used in this article, it was still interesting to read. Perhaps I should pick up Radiology more often?

1 Alexander Huppertz et al, “Nondestructive Insights into Composition of the Sculpture of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti with CT,” Radiology 251, no. 1 (April 2009): 236.

2 Ibid. On a side note, I think that this slight bump makes Barbra Streisand’s tribute to Nefertiti seem especially appropriate! This photograph of Streisand was taken in conjunction with a 1966 episode of “Color Me Barbra,” in which Streisand performs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art next to the bust of Nefertiti.

3 Ibid., 239.

4 Ibid.

Monday, March 23rd, 2009

A recent article in the New York Times caught my attention: Catholic indulgences are back.

Indulgences are an interesting topic in the history of art, particularly because the initial selling of indulgences brought about the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther was discontented with the Catholic church for many reasons, including the selling of indulgences. In 1517, he wrote 95 theses which outlined his discontent with the Catholic church. He nailed a copy of these theses onto the door of the Wittenburg church.

To retaliate against the Reformation, the Catholic church began the Counter-Reformation movement. It was hoped that the Catholics could reconvert any souls who had fallen astray to Protestant paths. The Counter-Reformation also allowed the church to defend itself against Luther’s criticisms. The Council of Trent was organized to help the church define the doctrines of the church and also rebuttal Protestant heresies. Also, the Council of Trent stipulated the purpose of art within the Church; these stipulations served as an outline for much of the art produced during the Baroque period.

I love Counter-Reformation (Southern Baroque) art because it is so propagandistic. The art and architecture is dramatic and emotional to help facilitate the process of reconversion. Here are a three of my favorite propagandistic pieces:

Bernini designed this piazza (plaza; 1656-1667) in front of St. Peter’s Cathedral (the seat of the Vatican). This photograph is taken from the top of the cathedral, looking outwards at the plaza. Many art historians discuss how the colonnade of Bernini’s piazza extends itself like two arms, reaching out and embracing those who walk up to the church. This can be interpreted propagandistically: it is as if the church is reaching out to welcome back anyone who was temporarily disillusioned by Protestantism.

To promote reconversion during the Counter-Reformation, there are many Baroque paintings which touch on this theme. I especially like Caravaggio’s painting of The Conversion of St. Paul (1600-1601). This painting is on the wall of the Cerasi Chapel (Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome), and the viewer of the painting is practically standing underneath Paul’s head. The painting is composed dramatically, with Paul’s foreshortened body pushed to the edge of the foreground; it is as if Paul’s body is about to spill out of the picture and land on top of the viewer beneath! Other dramatic elements, such as the tenebristic lighting (violent contrasts between light and dark) grab the viewer’s attention. Dramatic paintings intended to catch the viewer’s attention and evoke an emotional response that would help facilitate piety and reconversion.

To promote reconversion during the Counter-Reformation, there are many Baroque paintings which touch on this theme. I especially like Caravaggio’s painting of The Conversion of St. Paul (1600-1601). This painting is on the wall of the Cerasi Chapel (Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome), and the viewer of the painting is practically standing underneath Paul’s head. The painting is composed dramatically, with Paul’s foreshortened body pushed to the edge of the foreground; it is as if Paul’s body is about to spill out of the picture and land on top of the viewer beneath! Other dramatic elements, such as the tenebristic lighting (violent contrasts between light and dark) grab the viewer’s attention. Dramatic paintings intended to catch the viewer’s attention and evoke an emotional response that would help facilitate piety and reconversion.

Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Theresa (1645-52) is also located in a chapel (Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome). Oh man, there is so much to say in regards to this sculpture and propaganda. Once again, this sculpture propagandistically depicts a moment of conversion. After Theresa’s father died, she fell into a series of visions and trances. At this time, a fire-tipped arrow of Divine love was repeatedly pierced into Theresa’s heart by an angel. St. Theresa described this “experience as making her swoon in delightful anguish.”1 The dramatic quality of this sculpture is captured in the movement of Theresa’s heavy drapery. The drapery folds and falls around her body in a very energetic way, as if it has a life of its own. I also love the dark shadows that are created by the drapery folds. The contrast of the dark shadows and light marble reminds me of the tenebristic lighting that Caravaggio used in his paintings. The dramatic nature of this sculpture is enhanced because of its location; the niche of the chapel is crowned with a stage-like pediment and marble columns.

Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Theresa (1645-52) is also located in a chapel (Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome). Oh man, there is so much to say in regards to this sculpture and propaganda. Once again, this sculpture propagandistically depicts a moment of conversion. After Theresa’s father died, she fell into a series of visions and trances. At this time, a fire-tipped arrow of Divine love was repeatedly pierced into Theresa’s heart by an angel. St. Theresa described this “experience as making her swoon in delightful anguish.”1 The dramatic quality of this sculpture is captured in the movement of Theresa’s heavy drapery. The drapery folds and falls around her body in a very energetic way, as if it has a life of its own. I also love the dark shadows that are created by the drapery folds. The contrast of the dark shadows and light marble reminds me of the tenebristic lighting that Caravaggio used in his paintings. The dramatic nature of this sculpture is enhanced because of its location; the niche of the chapel is crowned with a stage-like pediment and marble columns.

The

Ecstasy of St. Theresa and

Conversion of St. Paul also are propagandistic because they depict Catholic saints. The veneration of saints was a practice that was denounced by the Protestants. Therefore, by depicting the moment of conversion for a saint, the Catholic church visually asserted its stance on saints and sainthood. (I have written a little more about the veneration of saints in Baroque art

here.)

What do people think about art and propaganda? Any thoughts on the return of indulgences? What Counter-Reformation works of art do you like?

1 Fred S. Kleiner and Christin J. Mamiya, Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, 12th ed., vol. 2 (Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2005), 696.

Thursday, March 19th, 2009

All of the sudden, today’s results from a Google search made me feel like I had a huge group of new friends.

Wednesday, March 18th, 2009

In recent editions of art history texts, the Mesolithic period (“Middle Stone Age”) is only briefly mentioned as a “transitory” era between the Paleolithic and Neolithic (“New Stone Age”) periods. I think that the word “transitory” is used because the early Mesolithic period was an age of hunting and gathering, whereas the end of the period saw the development of farming. In regards to art, though, I think this period is difficult to discuss because it is hard to interpret Mesolithic art. Soren H. Anderson points out that while some Mesolithic artifacts are decorated, we do not know the intent of the decoration. These objects could have been marked to indicate ownership, gender differentiation, or social rank.1 Any deeper symbolic meaning of these decorations is impossible without a knowledge of the mythology of the Mesolithic people.

In recent editions of art history texts, the Mesolithic period (“Middle Stone Age”) is only briefly mentioned as a “transitory” era between the Paleolithic and Neolithic (“New Stone Age”) periods. I think that the word “transitory” is used because the early Mesolithic period was an age of hunting and gathering, whereas the end of the period saw the development of farming. In regards to art, though, I think this period is difficult to discuss because it is hard to interpret Mesolithic art. Soren H. Anderson points out that while some Mesolithic artifacts are decorated, we do not know the intent of the decoration. These objects could have been marked to indicate ownership, gender differentiation, or social rank.1 Any deeper symbolic meaning of these decorations is impossible without a knowledge of the mythology of the Mesolithic people.

Some Mesolithic rock paintings that I like are located on the east coast of Spain. It is very likely that these paintings in shallow rock shelters originated from cave art. Above is a reproduction of a cave painting at Cingle de la Mola, Remigia (Castellon, Spain), c. 7000-4000 BC. The legs are spread wide apart, which suggests that the men in the group are either leaping or marching, perhaps in conjunction with a ritual dance. I think these paintings are interesting because they show individualized, descriptive features like the headdress of the leader. Art historically, these images are important because they show the human figure in a composite view – the torso is shown from a frontal perspective, whereas the legs and head are shown in profile. Obviously, it would be impossible for the human body to contort into this position, but the composite view allows for a more descriptive, detailed depiction of the human body.

There are other interesting artifacts from the Mesolithic period as well,  such as amber statues of wild boar from Scandinavia. In Norway, rock engravings of elk, furred creatures (such as foxes) and small whales have been found along the coast and freshwater concourses 1. I especially like the Azilian painted pebbles (shown left, c. 9,050 BC (c. 11,000 BP)) that come from the Mesolithic period. The function of these rocks is unknown; some scholars think that they might be for a cult ritual, but I am drawn to a different interpretation that the painted forms represent letters or numbers (some type of writing system).

such as amber statues of wild boar from Scandinavia. In Norway, rock engravings of elk, furred creatures (such as foxes) and small whales have been found along the coast and freshwater concourses 1. I especially like the Azilian painted pebbles (shown left, c. 9,050 BC (c. 11,000 BP)) that come from the Mesolithic period. The function of these rocks is unknown; some scholars think that they might be for a cult ritual, but I am drawn to a different interpretation that the painted forms represent letters or numbers (some type of writing system).

If you are interested in learning more about Mesolithic art, you might like to read this book.

1 David M. Jones, et al. “Prehistoric Europe.” In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.erl.lib.byu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T069317pg3 (accessed March 18, 2009).

2 Ibid.

Tuesday, March 17th, 2009

Mieke Bal’s book Looking In: The Art Of Viewing has forever changed the way that I look at exhibitions in art museums and galleries. In her chapter “On Grouping,” Bal discusses how the juxtaposition of different images on a museum wall can create meanings and connotations which never would have existed otherwise. She discusses a grouping of three paintings in a Berlin museum: Amor Vincit Omnia (Caravaggio), Doubting Thomas (Caravaggio, shown above) and also Heavenly Amor Defeats Earthly Love (Baglione). Specifically, she argues that the placement of Doubting Thomas between these two images of nudes creates a new dynamic within the first painting. For Bal, she feels like “Jesus’ barely visible leg at the lower left becomes slightly coquettish” when placed alongside Caravaggio’s nude Amor (whose sprawled legs cover a good portion of its canvas).1 If you’re interested, you can read parts of Bal’s argument and see a grouping of the three images online.

Mieke Bal’s book Looking In: The Art Of Viewing has forever changed the way that I look at exhibitions in art museums and galleries. In her chapter “On Grouping,” Bal discusses how the juxtaposition of different images on a museum wall can create meanings and connotations which never would have existed otherwise. She discusses a grouping of three paintings in a Berlin museum: Amor Vincit Omnia (Caravaggio), Doubting Thomas (Caravaggio, shown above) and also Heavenly Amor Defeats Earthly Love (Baglione). Specifically, she argues that the placement of Doubting Thomas between these two images of nudes creates a new dynamic within the first painting. For Bal, she feels like “Jesus’ barely visible leg at the lower left becomes slightly coquettish” when placed alongside Caravaggio’s nude Amor (whose sprawled legs cover a good portion of its canvas).1 If you’re interested, you can read parts of Bal’s argument and see a grouping of the three images online.

Since reading this article a few years ago, I am constantly looking for new meanings and connotations which come about because of the juxtaposition of images in a museum. A few years ago I helped hang an exhibition which featured work by the artist Sean Diediker. Due to the size of the paintings and the space of the museum, it ended up that a large painting of a female nude was placed to the left of a painting of Joseph Smith (the Mormon prophet) receiving a vision. Joseph Smith was kneeling down in semi-profile, looking at a vision that was placed to the left of the picture frame. If the picture frames between the nude and Smith were invisible, then the boy prophet would have been looking right at the nude woman. All of the sudden, the look of surprise and awe on Joseph Smith’s face began to look a little more embarrassed, as if he wasn’t supposed to be staring at a nude female!

As Bal points out in her book, every viewer brings their own personal experiences (“cultural baggage”) and past to a work of art. Therefore, we all have our own personal reaction to what kind of dialogue and connotations are created by a work of art. The writer of this article reacted to a past installation at the Whitney Museum (shown below), saying that “the juxtaposition of Urs Fischer’s Intelligence of Flowers (holes in the wall) and Untitled (hanging shapes) with Rudolf Stingel’s black & white photorealistic self-portrait creates an impression of crushing despondency in the face of a wrecked world.”

I agree that such a reaction to this exhibition of art is possible. Personally though, having just seen a recent episodes of LOST that involve swinging pendulums and abandoned Dharma Initiative stations, I can’t help but think of anything else when I look at these hanging shapes, circles, and gaping holes.

I agree that such a reaction to this exhibition of art is possible. Personally though, having just seen a recent episodes of LOST that involve swinging pendulums and abandoned Dharma Initiative stations, I can’t help but think of anything else when I look at these hanging shapes, circles, and gaping holes.

Have you ever found interesting connotations or dialogue that was created by the juxtaposition of artwork? What kind of personal “cultural baggage” has affected your reaction to a work of art?

1 Mieke Bal, Looking In: The Art Of Viewing (New York: Routledge, 2000), 184.

The shaping of the eyelid corners on the outer (visible) surface can be seen on the right (indicated by *). On the inner core (left) creases in the corners of the mouth (arrows) were found.

The shaping of the eyelid corners on the outer (visible) surface can be seen on the right (indicated by *). On the inner core (left) creases in the corners of the mouth (arrows) were found.