Sunday, September 8th, 2019

A Recent Addition to “The World Stage: Brazil”

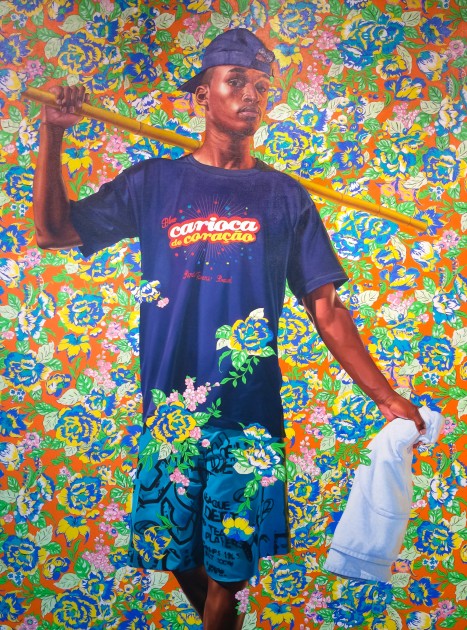

Kehinde Wiley, “Indio Cuauhtemoc: The World Stage, Brazil,” 2017. Oil on canvas. Photo taken by the author

Last month I visited the Portland Art Museum and saw a painting by Kehinde Wiley that I hadn’t seen before. This painting is currently on display as a loan from the collection of Arlene and Harold Schnitzer, major philanthropists in the area (Harold passed away in 2011). I already was familiar with Wiley’s series called The World Stage that feature people from countries around the world, but I wasn’t familiar with this one that comes from the Brazil installment of The World Stage. And as I’ve studied this work, I realized that this painting was made fairly recently, in 2017, almost ten years after the initial series was begun and exhibited. The painting isn’t listed as part of Wiley’s Brazil series, and I wonder why Wiley decided to create this painting so much later. Did he have all of the source material and photos of the model from before, but simply ran out of time to start this painting until almost a decade later?

Wiley began this project through a residency in Rio de Janeiro in March 2008 and exhibited the installation in 2009. At the time, a short book was published with two essays and images of the exhibition painting, and similar books were produced for other installments of The World Stage. The exhibition aimed to draw attention to issues of Afro-Brazilian identity and the complex and problematic social issues created due to the history of slavery and colonialism in Brazil. As a result, Wiley’s Afro-Brazilian figures are positioned in compositions that are reminiscent of famous paintings and monuments in Brazilian culture. Here are a few examples:

- Wiley’s painting “Omen Negro (Black Man)” refers to a watercolor by the German artist Zacharias Wagener (who was in Brazil when the Dutch were there). Ironically, Wagener’s watercolor is actually a copy of another painting titled “African Man” by Albert Eckhout, so there are multiply layers of copying and appropriation that are taking place. Furthermore, the title of this work seems have layers of appropriation and inadvertent spelling corruption: Wiley’s phrase “Omen Negro” is a corruption of Wagener’s title “Omem Negro,” which itself is a corruption of the accurate Portuguese phrase “homem negro” (“black man”).

- Wiley’s painting “Marechal Floriano Peixoto” copies the composition of a monument in Cindelândia’s public square in Rio de Janiero. The monument honors the second president of the Republic, Floriano Peixoto, but these two particular figures represent the indigenous people of Brazil. The inclusion of these active, strong figures and their composition alludes to the colonial presence in Brazil and the subjugation of the native presence by the Portuguese. Other allegorical figures in the monument recognize the African, Portuguese, and Catholic aspects of Brazilian history.

- Wiley’s “Alegoria a Lei do Ventre Livre” is inspired by a gesso sculpture by A. D. Bressae of the same title. Kimberly Cleveland explains that this allegorical figure is an reference to the 1871 law which declared that the children who were born to slave parents would be free. She writes, “The irony of this law is suggested in the less-than-enthusiastic expression of Wiley’s model,” but absent from the original, nineteenth-century sculpture” of a smiling boy.1

- Wiley has multiple paintings (see one, two and three) dedicated to Alberto Santos Dumont, an innovator in aviation. The compositions for these paintings come from a monument honoring Dumont, located outside of the Dumont airport in Rio.

The influence of Brazilian monuments on the composition brings me back to the new Kehinde Wiley addition to this series: this 2017 painting is inspired by a monument of Cuauhtemoc that is located in the Parque do Flamengo in Rio de Janeiro.

Left: Kehinde Wiley, “Indio Cuauhtemoc: The World Stage, Brazil,” 2017 (photo taken by the author). Right: Monument to the Indio Cuauhtemoc in Rio de Janeiro. Image courtesy Wikipedia

The monument itself is a bizarre connection to Brazil, because is quite oblique. The statue is in Brazil because it was a gift from Mexico in 1922, to recognize the 100th anniversary of the Brazilians’ independence from Portugal in 1822. The statue depicts Cuauhtemoc, the last Aztec emperor, who ruled between 1520-1521 and then was executed by the Spanish. Perhaps there is a loose parallel between the end of an indigenous empire and the end of a colonial period, but it is a little bit of a stretch. Nonetheless, the sculpture is seen as a symbol of friendship between Mexico and Brazil.

By assuming the same composition as the Cuauhtemoc sculpture in Brazil, which is itself a copy of an original 1887 sculpture by Miguel Noreña in Mexico City, Wiley’s painting continues to add layers of appropriation and meaning. One theme is of connections and friendships between countries, since Wiley, as an American painter, took temporary residence in Brazil and painted Brazilian subjects. By depicting an Afro-Brazilian model, Wiley also touches on colonial history and those who were conquered and subjugated by Europeans, Africans and Aztecs alike.

Kehinde Wiley, detail of “Indio Cuauhtemoc: The World Stage, Brazil,” 2017. Oil on canvas. Photo taken by the author

Kehinde Wiley, detail of “Indio Cuauhtemoc: The World Stage, Brazil,” 2017. Oil on canvas. Photo taken by the author

The casual clothing of Wiley’s subject allude to commodifications by referencing popular (American) fashion and culture. In addition, the bright colors and thriving flowers also connect to Western commodification, suggesting how “the exotic” is a Western construct that has been fetishized and desired. The inspiration for at least one backgrounds in the series came from textiles found at the Sahara market in Rio, and perhaps this design may have been found in a similar place.2 I noticed that Wiley used this same floral background in a study for a painting called “Sidney da Rodra, Jr.” (2008), but it doesn’t appear in the final version, and a detailed image of this same floral background appears as an unlabeled plate at the beginning of the World Series: Brazil book.3 So Wiley was thinking about this background during this project and studying it, even though this painting wasn’t made (or perhaps finished?) until 2017.

The layered appearance of human figures and decorative patterns in Wiley’s paintings are an appropriate visual reminder of the layers of meaning and appropriation. Typically, Wiley’s paintings have a few elements from the background which extend out of their pattern to partially cover the clothing of the subject. This can be seen best on the t-shirt and the shorts of the “Indio Cuauhtemoc” figure by Wiley, which are partially covered with flowers. Such layers remind us that, despite the real life issues that Wiley addresses, he has presented them to us in a fictive environment to remind us that all the world is a stage and his “streetcast” models are actors.

1 Kimberly Cleveland, “Kehinde Wiley’s Brazil: The Past Against the Future” in Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Brazil by Kehinde Wiley (Roberts & Tilton, 2009), 26.

2 Kehinde Wiley, Kehinde Wiley: The World Stage: Brazil (Roberts & Tilton, 2009), 12.

3 Ibid., 4, 45.