Tuesday, March 31st, 2015

Presence and Absence at the Gardner Museum

My family and I recently returned from a trip to Boston. One of the main reasons I wanted to go to Boston was to better understand and analyze the gallery space in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Long-time readers of this blog may recall my fascination with this American art collector; several years ago I wrote a post on how Mrs. Gardner (called “Mrs. Jack” by her friends) is a “female subject” that visitors encounter when they visit the space.

As I analyzed the museum space last week, I do feel like my observations about a “female subject” were justified. In fact, in a broader sense, I think that Isabella’s subjecthood and presence were very much part of the museum, despite her obvious absence (Isabella died in 1924). On one hand, the whole curation of the museum is an indication of Isabella’s presence, since she stipulated in her will that the objects in the museum should be kept just as she had arranged them. But objects throughout the museum, specifically the “palace” (the original museum), also hinted at the collector’s presence and absence.

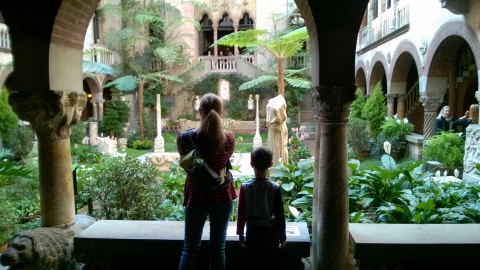

Upon entering the Garden Court of the museum, I first became aware of Isabella’s simultaneous presence and absence through a printed guidebook that is placed in the garden to orient visitors. The guidebook specifically explains that Mrs. Gardner liked to sit in the Roman marble throne (shown above), among other representations of classical figures and goddesses. The guidebook then presents the question, “Could it be that [Mrs. Gardner] was setting a place for herself in the company of these powerful women?”1

For me, this brief inclusion in the guide helped to build up the idea of Isabella’s presence within the space, by drawing attention to the fact that she physically sat among her works of art. However, the guide simultaneously draws attention to the fact that the marble throne is now vacant, without a sitter, which is also made apparent by the guide’s discussion of Mrs. Gardner in the past tense. So, this marble throne gave off a presence and a void.

Mrs. Gardner’s presence and absence was also included in the museum in other ways as well. One of the most interesting inclusions for me was not through a painting or sculpture, but a piece of fabric. In the Titian Room, on the wall just underneath Titian’s Rape of Europa, Mrs. Gardner placed a piece of silk that was taken from a gown which was designed for her by Worth of Paris. A catalog for the museum explains that the color and tassel pattern complement the nearby end tables, but I think that this silk fabric suggests much more.2 In an indirect way, this silk fabric hints at an embodiment of Mrs. Gardner and her physical presence, since she herself wore this fabric as a ball gown. However, the idea of absence is implied in two ways: 1) the fabric is not part of a dress, and therefore not part of Mrs. Gardner’s body or presence and 2) the current fabric displayed is a reproduction, not the original that was once physically associated with Mrs. Gardner.

Probably the most obvious indication of Mrs. Gardner’s presence and absence throughout the museum are the portraits of her which are scattered throughout various rooms. Some examples are Mrs. Gardner in White in the Macknight Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner in Venice in the Short Gallery, as well as Study for Isabella Stewart Gardner in Venice in the Blue Room. These portraits suggest the presence of the sitter through their visual reproduction of Mrs. Gardner’s likeness, but the portraits’ mere presence in the gallery space also suggests that they are substitutes for an actual person who is absent. Probably the most striking and poignant example of Mrs. Gardner’s presence is in the Gothic Room on the third floor of the museum, just as as the visitor is completing their survey of the museum as a whole. In this space is placed Sargent’s imposing Portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner (1887-1888, shown above), which was painted when she was forty-seven years old.3 The painting is placed in the corner of the gallery (so it is the focal point of the room, regardless of which entrance is taken). After having subtle hints at both the presence and absence of the museum collector throughout the whole space, I felt like with this imposing, life-size portrait I was getting as close to the physical presence of Isabella as possible. I think a visitor could make no mistake as to who is the powerful benefactor who created and controlled their gallery experience, after being faced with this frontal, full-length portrait!

South Wall of the Dutch Room in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Room. The frame on the left held Rembrandt’s “A Lady and Gentleman in Black” (1633) and the frame on the right held Rembrandt’s “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee” (1633)

On a side note, I’ll also just add that today the Gardner Museum embodies the idea of presence and absence in another way too: the empty frames for the stolen paintings in the Dutch Room are still on display, suggesting both a presence and unsettling void for these works.

Have you ever been to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum? Can you think of other instances in which her presence and absence are simultaneously emphasized to the visitor?

1 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Garden Court guidebook, unpublished. March 2015.

2 The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: A Companion Guide and History, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), p. 118. Frederick Worth designed this fabric around 1890.

3 Sargent also painted Isabella’s portrait in 1922 (titled “Mrs. Gardner in White”) it was painted three years after a stroke which paralyzed Isabella’s right side.