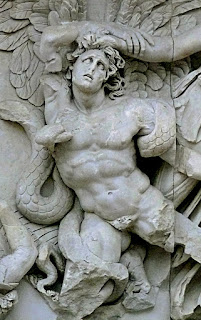

This week my students and I have been talking about whether the Parthenon Marbles (sculptures from the Parthenon which are currently in the British Museum, also called the Elgin Marbles) should be returned to Athens. The Greeks perceive the removal of these sculptures in the early 19th century as an ethical injustice to their people, partially since they were removed by the British ambassador Lord Elgin during a period of Ottoman occupation in Greece. The Greeks have already prepared a space to house these sculptures, in the relatively new National Archaeological Museum building in Athens. In fact, activists are noting that next month marks the “black anniversary” of when the Parthenon sculptures arrived in the British Museum 200 years ago (on June 7, 1816). A recent news article explained that the Greeks are noting this historical marker by putting extra pressure on the British to return the sculptures.

I personally can see validity in reasons for why the sculptures should remain in London, as well as reasons for why they should be returned to Athens. These sculptures are part of both British and Greek history, not to mention the constructed Western canon that still exists today.1 My goal in exploring this debate with students is to help them understand how this controversy about ancient art helps to reveal historical and current values regarding art and culture.

As my students and I have been talking about the mounting pressure to return these sculptures to Greece, I have been thinking about how the act of restitution and repatriation is becoming a common practice. In fact, there has been more discussion of restitution and repatriation in the past few decades, especially for the Parthenon Marbles, than there have been since the 19th or early 20th centuries.

I think that there are several reasons for why art restitution is so popular and upheld today, but I personally think that there is one historical reason which has served as an major impetus in the past several decades. I asked my students what they thought might be this impetus for restitution, and I also asked why they think that today we are culturally uncomfortable with the idea of imperialism or a country/group/individual asserting power over another. Our discussion went something like this:

Student 1: We care about restitution and righting wrongs today because of the feminist movement of the 1960s.

Me: I think that helped to open up the door for it, especially in recognizing minorities and women. But I think we can go even further back in time. What else happened in the 20th century which contributed to our current interest about restitution?

Student 2: Well, as students, our generation cares about social justice today. We are trying to be sensitive to the needs of minorities and underrepresented groups of all kinds, including those of different sexual orientations and religious minorities.

Me: Social justice is valued today. But why is that the case? Why do we care about social justice now instead of a century ago?

Student 3: Maybe the Civil Rights Act led us to care about social justice?

Me: I think the Civil Rights Act is part of it. But what else happened in the 20th century to draw awareness to social injustice? What previous events were perceived as unjust?

Student 4: World War Two and the Holocaust! In another one of my classes we have been talking about the long-lasting and devastating effects of this war.

Me: Yes! This is what I think too! I think that today we are uncomfortable with imperialism and nationalistic conquest because of what Hitler and the Nazi party did, especially because the Nazis are responsible for the horrific mass killings of the Jewish people during the Holocaust. World War Two haunts the collective memory of our culture today, and for good reason. I think that World War Two will continue to shape and inform the way that we approach social justice, art and restitution for the rest of our lifetimes. All of these events that you have mentioned, like the Civil Rights Act and the feminist movement, have happened in the aftermath of World War II. And consider, for example, the stories that have appeared in the news of paintings and objects that have been returned to Jewish families after they initially were stolen by the Nazis during the World War Two era. Perhaps some of you have seen the Woman in Gold movie that was released last year, which followed the restitution of a Klimt painting to a Jewish family. This is just one example of restitution art; there are many more examples of restitution have occurred and many lost objects which still need to be found and returned.

Being influenced by such cultural memory of the Holocaust and Nazi party isn’t a bad thing at all – but it is good to realize that what we are experiencing is a cultural mindset (even a perhaps a trend, if you will). If the Parthenon Marbles do go back to Athens, we should realize that we will be making a statement about our own current values and cultural memory through the sheer act of restitution. And I hope, for that reason, that if the Parthenon Marbles ever do go back to Athens, that copies will be placed in the British Museum so that we can continue to have a dialog about changing cultural values and why these statues have traveled across Europe over the centuries.