Sunday, September 22nd, 2013

War and “Place de la Concorde” by Degas

Last night, I watched The Rape of Europa PBS documentary about Nazi looting during the World War II era. Near the end of the film, I was surprised to see Edgar Degas’s painting Place de la Concorde (1875, shown above) appear on the screen. This painting apparently resurfaced in 1995 after having been missing for four decades. Place de la Concorde was brought to Russia by Soviet “trophy bridgades” after World War II. These Russians had been sent to Germany to reclaim the stolen art which the Nazis had taken from Russian collections. In addition to reclaiming art which had been taken in the first place, some of these “trophy brigades” retaliated and decided to help themselves to works of art held in German collections. Such is the case with Place de la Concorde, which was taken from the collection of the German collector Otto Gerstenberg. It is likely this shady history contributed to the reason why this painting was held from public view for four decades. Today, the painting is a celebrated work in the Hermitage Collection and was featured in a six-month exhibition which ended at the beginning of this year.

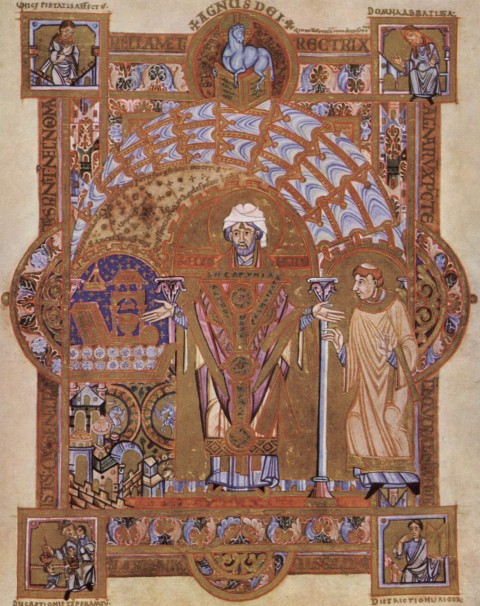

The current context and location of this painting in the Hermitage Museum is interesting to me on several levels. On one hand, the subject matter and of this painting (especially what intentionally is not depicted in this scene) raises some interesting contrasts in relation to the current Russian ownership. Back when Degas painted this scene, only a few years had passed since the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) and the bloody civil war in Paris, the Commune (1871). During that time, the French lost the territory of Alsace-Lorraine to the Prussians. As a result, a statue by James Pradier that was located in Place de la Concorde, The City of Strasbourg (1836-38, shown below) came to be seen from 1871 onward as a symbol of the lost territory. The statue was draped in black on state occasions and occasionally decorated with wreaths until France regained the region in following World War I.

James Pradier, "The City of Strasbourg," 1836-38. Place de la Concorde, Paris. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Degas, however, chose to not depict The City of Strasbourg in his painting; the statue would have been draped in black to mourn the loss of the territory, therefore serving as a direct reference to the war and destruction which recently took place in France.1 Instead Degas intentionally removed this statue and reference to war with his strategic placement of the striding figure of Baron Lepic. Degas, along with other Impressionists, sought to escape from and ignore the death of the French and Parisians (and the figurative death of the territory of Alsace-Lorraine) by not referencing the recent wars in their Impressionist art.2 In contrast, with the placement of Place de la Concorde in the Hermitage Museum today, it seems as if the Russians are trying to compensate for the death of their people (1.6 to 2 million Soviets died in the Siege of Leningrad during 1941-1944) by keeping this trophy painting that once belonged to a German collector.

Although in the 19th century Degas tried to avoid a direct reference to war, this painting no longer can function in that way. The current context and placement of Place de la Concorde within the Hermitage Museum has created a new meaning for this painting which is intrinsically linked to war. The current museum label at the Hermitage proudly displays that this painting came “from the collection of Otto Gerstenberg.” This painting has changed in its function due to its current context, arguably and ironically opposite to what Degas intended in relation to its subject matter.

In 1997 the Russians created a law which claimed that this painting, along with other “displaced” trophy items that were part of the Russian post-war expedition, are inalienable property of the Russian Federation. The painting is now displayed in the Hermitage with a dark brown frame, which reminds me a little of the dark drapery which would have cloaked the statue that represented the lost territory of Alsace-Lorraine. Although Degas didn’t want to depict the draped Strasbourg statue within his painting, Place de la Concorde itself is now cloaked in a state of mourning, serving as a reminder of the past and the loss of Russian lives.

1 Paul Wood, “The Avant-Garde and the Paris Commune,” in The Challenge of the Avant-Garde (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 122.

2 Ibid. Paul Wood discusses how “The Commune and the Prussian war silently haunt Impressionist painting in small tics and changes in viewpoint,” which includes the striding figure of Baron Lepic.