I belong to a really fantastic book group. This month we have been reading The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory by Carol J. Adams. This book is really fascinating to me. It explores how meat consumption is related to patriarchal values; meat has longstanding associations with power, strength, virility, and wealth. Adams makes some interesting parallels with how the “masculine” consumption of meat is related to the sexual consumption and objectification of women, too. (You can get a sense of the parallels made between meat and women-as-meat in Adam’s slideshow.) There is a lot more to this book too, and I would highly recommend it to anyone interested in theory, literature, or the history of vegetarianism.

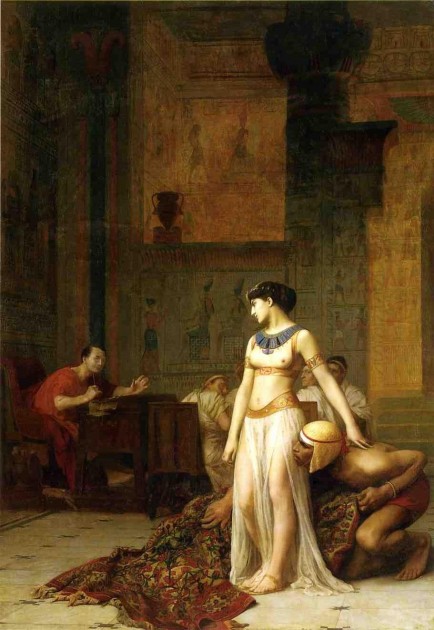

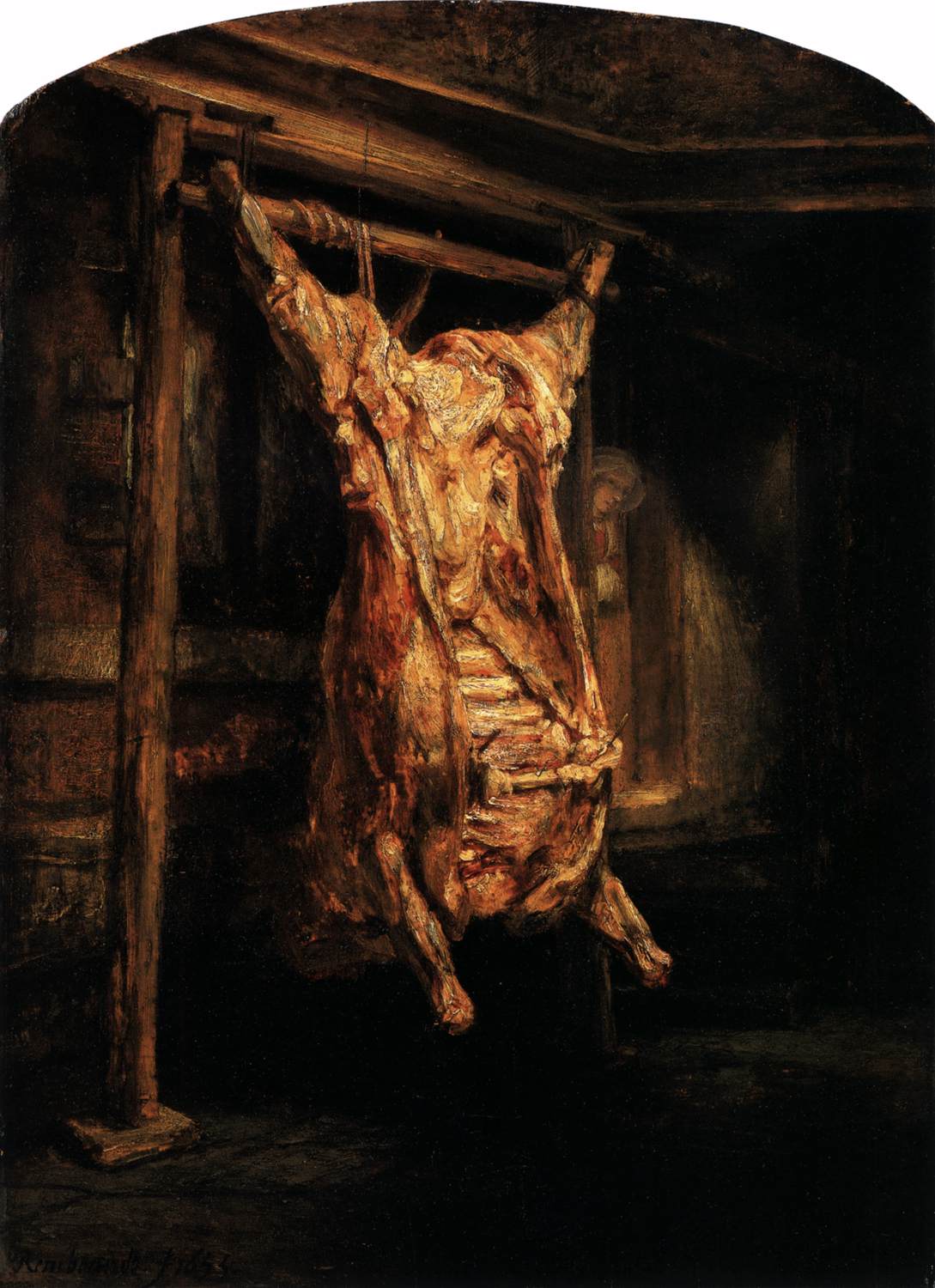

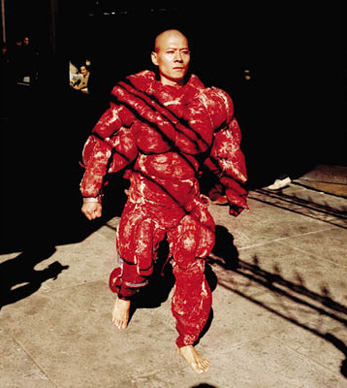

While reading this book, I continually thought of how meat is represented in art and visual culture. Although I have yet to read Adam’s other book, The Pornography of Meat, I feel like I’ve already come up with a substantial list. In many ways, the following representations of meat can also be related to patriarchy and power. I find it telling that the majority of the depictions of meat (that I have come across, at least) were created by men. And I also think it’s interesting that male artists like Rembrandt and Snyder (see below) decided to include women with the carcasses of dead animals. Are these artists merely referencing the fact that women have been delegated the responsibility to prepare meat (for male consumption)? I think we can we make deeper associations between what objects are construed for “the male gaze” in these images, especially from our modern-day perspective.

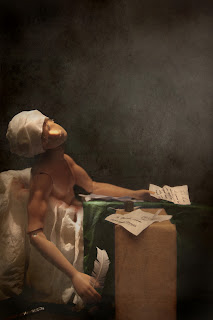

Rembrandt, "The Slaughtered Ox," 1655

Frans Snyder, "The Pantry," c. 1620

Along these lines of sexuality and male consumption, it is especially interesting to consider how Snyder depicted the maidservant with birds on a platter. The Dutch word “vogelen” (which means “to bird”) not only refers to fowl, but also to the sexual act. This painting, therefore, seems to reference worldly temptations or physical love.

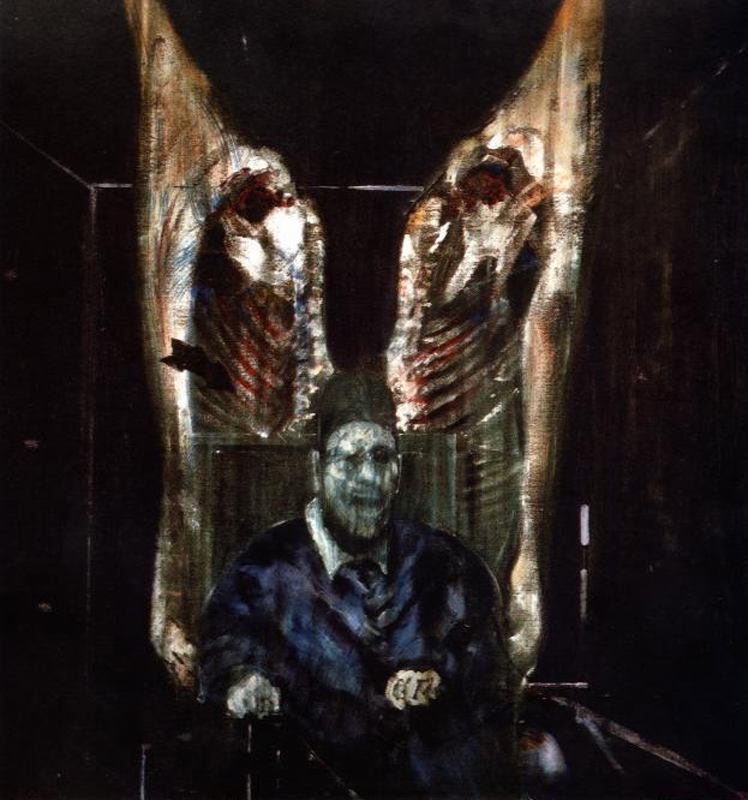

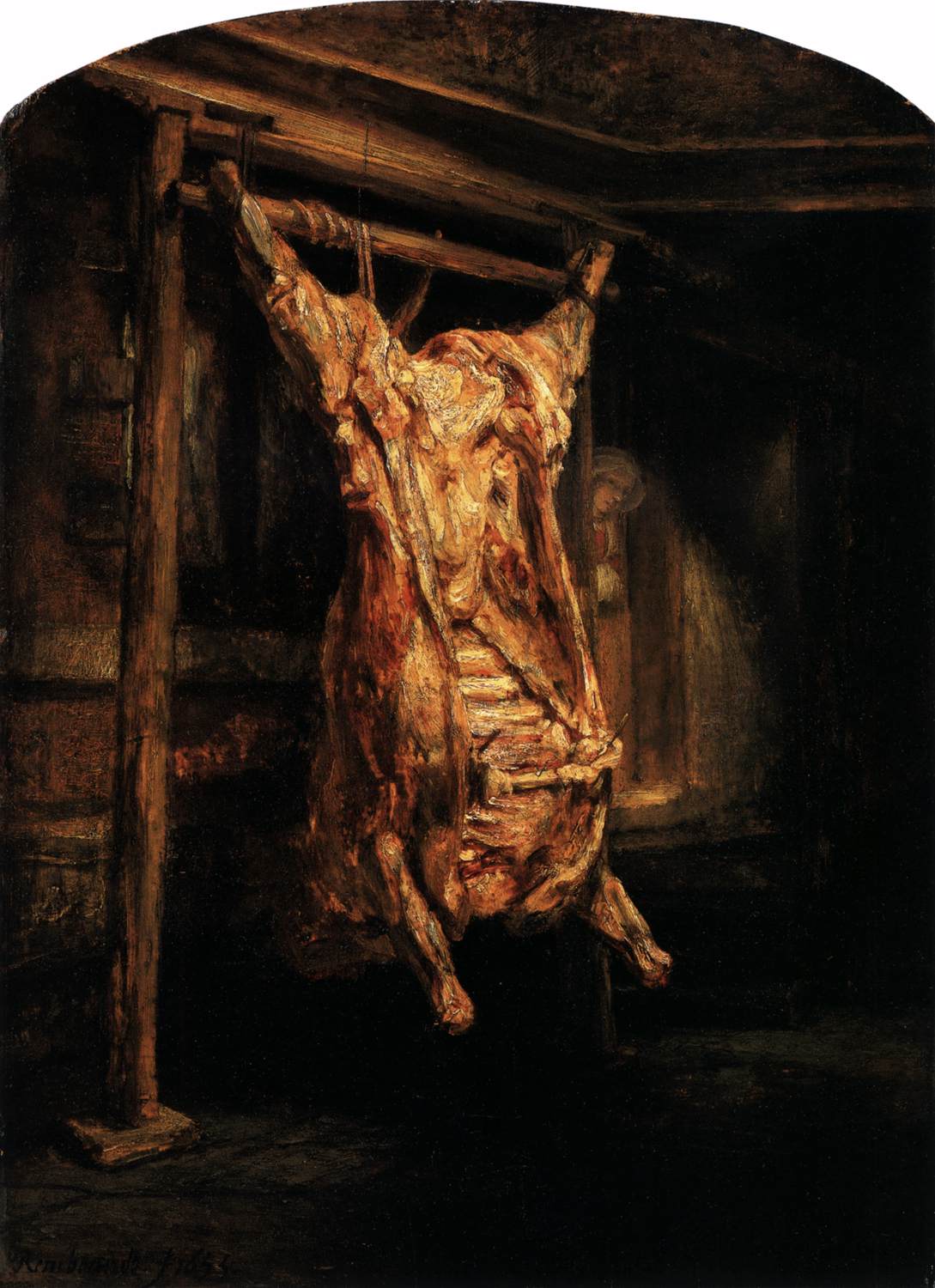

Artists in the 20th century also were interested in exploring “meaty” subject matter. One work of art that immediately comes to mind is Francis Bacon’s Head Surrounded by Sides of Beef (1954, see below). As an air raid warden in London during WWII, Bacon saw many of the horrors of war (a grisly enterprise which, I think, can be interpreted in many respects as a “masculine” endeavor). With two slabs of meat flanking the sides of a ghostly figure, Bacon explores parallels between meat and death.

Francis Bacon, "Head Surrounded by Sides of Beef," 1954

Other 20th century artists have made some interesting parallels between meat and male consumption, including the Surrealist artist Meret Oppenheim. Her work, The Governess (see below) depicts a pair of stilletto heels (objects which can signify female sexuality and arousal). The heels are tied together and decorated with paper crowns – the type of decoration sometimes found on a leg of lamb or chicken.

Meret Oppenheim, "My Governess," 1936

One of the most influential works of art involving meat is Carolee Schneemann’s performance Meat Joy (1964). This performance, which is very aggressive and controversial, involved men and women who danced, rolled on the floor, and played with a mixture of raw flesh (e.g. partially-plucked bloody chickens, raw fish, and raw sausages). The sexual connections between meat and “pleasures of the flesh” are quite clear in the performance.

I also think that it is unsurprising that audience members would squirm during Meat Joy. After all, Schneeman is including bloody and partially-plucked chickens, something that relates to what Carol Adams calls the absent-referent. When people consume animals today, the flesh is usually cooked and modified (and sometimes given a different name than the actual animal, like “veal” or “beef”) to help obscure the reality that a once-living creature has comprised the meal. So, in essence, animals are absent–referents on the dinner table. They are there, but they are also not there. Schneeman’s aggressive reference to flesh and blood in her “happenings” performance restores the absent-referent, which undoubtedly contributed to why viewers squirmed.

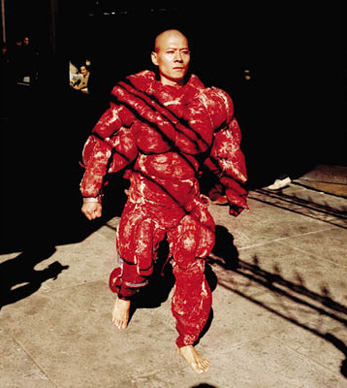

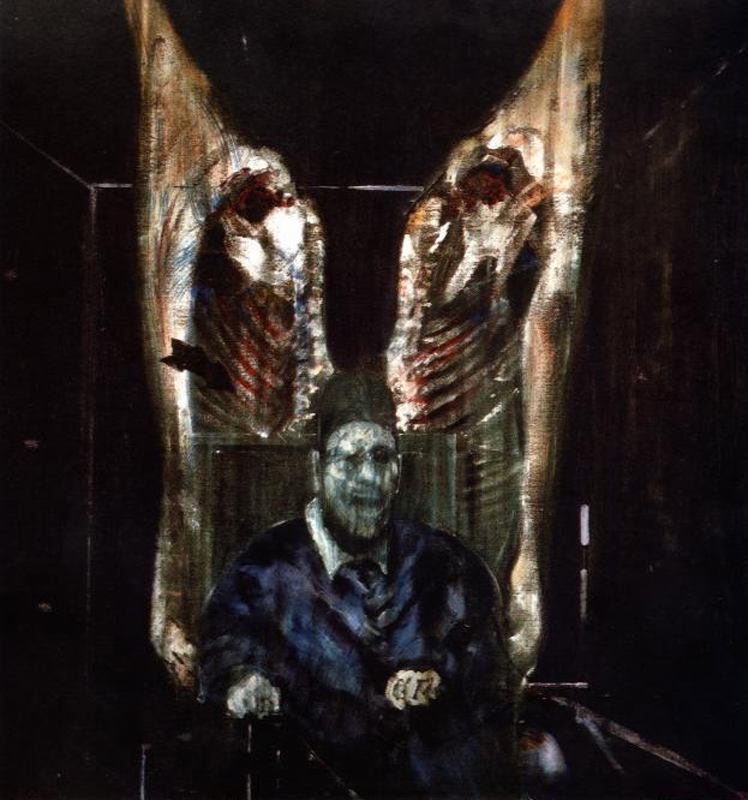

Many artists have been influenced by Carolee Schneeman. In fact, in 2008 exhibition titled Meat After Meat Joy brought together the works of various artists who have explored different meanings between meat and flesh. (You can read one blogger’s take on the exhibition here.) One of the videos on display in this exhibition was Zhang Huan’s performance, My New York (2002, see below).

Zhang Huan, "My New York," 2002. Video still from performance.

Many of Huan’s performance works involve endurance and masochism. In this particular performance, Huan walked through New York wearing a heavy suit with actual pieces of raw beef. Looking like a “beefed-up” body-builder (which alludes to masculinity and virility!), Huan would occasionally release doves during the performance. It was interesting to interpret this performance in a political light, given the recent 9/11 attacks. The small figure of the artist (within the powerful, beefy costume) was a reflection on how America (and New York itself) were vulnerable – as a nation and as a city.

And finally – I can’t finish this post without a pop culture reference. Lady Gaga has clad herself in “meaty clothes” a few times, once in a meat bikini on the cover of Vogue Hommes Japan. Soon after, Lady Gaga also appeared in a “meat dress” at the 2010 Video Music Awards, complete with a steak on her head (see below).

Lady Gaga's "meat dress" at the VMA music awards, 2010

Although Lady Gaga said in an interview that her dress was a statement about fighting for rights (and asserted “I am not a piece of meat”), I can’t help but see how her dress just reinforces the associations with the masculine consumption of women (which other feminists, including Carol J. Adams, have observed). In this outfit, I think Lady Gaga is suggesting that she is available for consumption on two levels: to satiate sexual and physical hunger. And because of the associations with animals and meat, Lady Gaga seems to reinforce her sexuality by suggesting that she, too, is animalistic.

Any thoughts? Have I spoiled your appetite? (Sorry!) I’m curious to see what other depictions of meat are out there. Do you know of any more? I’m also reminded of Pieter Aertsen’s two works The Butcher’s Stall (1551) and Cook in Front of a Stove (1559). Another example is Van Gogh’s Still Life with Apples, Meat, and a Roll (1886).