Saturday, July 28th, 2012

Mount Rushmore and the Statue of Liberty

Fréderic-Auguste Bartholdi, "Liberty Enlightening the World" (known as the "Statue of LIberty"), 1870-86. Hammered copper over wrought-iron pylon designed by Gustave Eiffel. Height from base to top of torch 112' (33.5 m). Image courtesy Wikipedia.

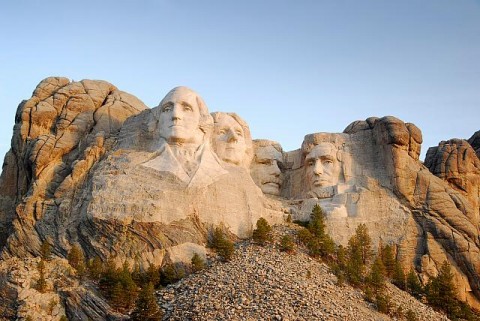

I have a quite a hoard of art history books in my possession. Out of all of my books, I only have one survey textbook which mentions the Statue of Liberty.1 None of my textbooks mention Mount Rushmore. Since these monuments have iconic status in American culture, I was surprised to realize yesterday that these monuments don’t really factor into the realm of art history (especially in the United States). Likewise, the sculptors Bartholdi and Borglum are hardly household names among Americans.

My husband and I discussed this topic yesterday, after seeing an image of Mount Rushmore on a television screen. We came up with a couple of theories as to why these monuments are not discussed in art history very much. I thought I’d jot them down here, and see what others think:

- These sculptures are not studied in art history because they aren’t influential. (My husband put forward this idea. I have some issues with this theory, because the word “influence” can be defined in different ways. Perhaps nineteenth-century artists did not copy Bartholdi’s sculpture, but the Statue of Liberty factors into Pop art, as can be seen in the work of Andy Warhol and others.)

- These sculptures are not the best representatives of the art which was popular in the late 19th and early 20th century. As a result, textbooks and instructors opt to discuss other works of art.

- These sculptures didn’t have international influence, which could account for their omission in broader, internationally-focused textbooks.

- These works are relatively ignored by art historians because they are recognized (either consciously or subconsciously) as monuments instead of sculptures. Along these lines, perhaps the iconic status of these sculptures precludes these pieces as being examined as works of art.

- Perhaps the location of these sculptures (i.e. in a harbor and on a mountainside) do not encourage the pieces to be appreciated for aesthetic reasons. Although I think that these sculptures are just as iconic as Michelangelo’s “David” (at least among Americans), these two sculptures are not displayed in an art museum.

- Since the creation for each of these monuments is connected to socio-political history, these sculptures have been overlooked in the art historical discipline. (Could this perhaps be indicative of how the disciplines of history and art history do not always intersect?)

What do others think? Did you ever learn about the Statue of Liberty or Mount Rushmore in an art history class? If so, what did you discuss? If you’re curious to learn more about these two American monuments, I have a few sites and images to recommend:

- The History of the Statue of Liberty (National Park Service)

- Statue of Liberty Pictures: Rare Views, Inside and Out (National Geographic)

- Sabotoge in New York Harbor (Smithsonian). This article is about the Black Tom explosion on July 30, 1916. The explosion caused over $100,000 of damage to the Statue of Liberty. Ever since this event, the interior of the torch has been closed to visitors.

- Sculptor Gutzon Borglum (.PDF file, National Park Service)

- The Making of Mount Rushmore (Smithsonian)

- Gutzon Borglum’s Model of Mount Rushmore (The original design was never realized, due to lack of funding.)

- Construction of Mount Rushmore (short video clip, Human Films Studies Archives, Smithsonian). Notice how the head of Thomas Jefferson was originally placed on the left of George Washington. Jefferson’s unfinished head had to be blasted off, however, due to poor rock quality. Borglum then placed Jefferson’s portrait on the other side of Washington’s portrait.

1 David G. Wilkins, Art Past Art Present 6th ed., (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson, Prentice Hall, 2009). 432.

Hm, I don’t know, but to me the most likely explanation for the neglect of these monuments in art history would be the simple fact that from an aesthetic point of view both the Statue of Liberty and Mount Rushmore are (to put it mildly) a tad on the conservative side, while art history textbooks tend to focus on works and movements that were new and innovative in their time.

As far as I know, monumental sculpture is not treated any differently from other kinds of sculpture in the ancient world. Why should it be different for these pieces?

One explanation might be their political implications. In today’s academic world, where post-colonialism is bread and butter, the settings for each work are suspect. “Give me your tired, your poor,” is not longer a beacon of hope, but rather rings hollow against issues of income inequality and (alleged) anti-immigrant policy. And little explanation is needed for Mount Rushmore, a defacement of Indian tribal land.

Still, it puzzles me why these kinds of ‘imperialist’ enterprises should be ignored, while Augustan propaganda pieces like the Ara Pacis get attention. Is it the profound distance between us and the early Roman Empire which eases intellectual’s frustrations?

I remember reading several articles on The Statue of Liberty, which were really interesting, but nothing on Mt. Rushmore.

That being said, there is a lot of literature about monuments out there, and I think it’s an emerging part of art history. I just published an article about a labor monument near to where I grew up. I think it’s tough for traditional art historians to write about monuments because they don’t fit comfortably into a lot of theoretical frameworks; but most Americans these days experience public art through monuments. So it’s an important segment of art to look into, imo.

Interesting topic, and I’m also inclined to think that social histories of art might be more inclined to include the monuments than ones based on notions of aesthetic innovation. (Compare with the Vietnam War Memorial, which can easily be related to both types of account.)

And then, to add to your comment about their status as icons, there’s the issue of the place the monuments occupy in American patriotism / nationalism… Perhaps academic types–like myself!–aren’t entirely comfortable with this?

Bit off topic, but here’s a random association: both monuments appear in the climaxes of Hitchcock films (Mt Rushmore in North by Northwest, and the Statue of Liberty in Saboteur).

Thanks for the comments, everyone! I think that everyone has brought up some great points. I really like Jon’s point about how political monuments have had a longstanding place in art history, so these monuments should not be any different. However, Ben brings up a good point about patriotism. Perhaps academics aren’t comfortable with patriotism, since it could imply a bias or privileged attitude toward a work of art (especially if an American is writing about the Statue of Liberty or Mount Rushmore).

It is interesting that more conservative monuments (artistically speaking) are not discussed in art history textbooks. I guess this is just another manifestation of how art historical textbooks are not necessarily an accurate or comprehensive discussion of the the past. We write today about what we privilege. In this case, it seems apparent that the innovative, avant-garde mindset is still valued in art history, to the exclusion of other works of art. And like heidenkind implied, art historians today also value theoretical frameworks. Perhaps these monuments are too difficult to discuss within theoretical frameworks (although a postcolonial or postmodern analysis may be in order?).

In thinking about this topic over the past few days, I’ve thought about how these monuments can factor into the greater spectrum of art history. Don’t you think some interesting comparisons and contrasts could be made between Mount Rushmore and, say, the Great Sphinx?

Oh and Ben, I’m glad that you brought up the Hitchcock connections! I thought about the “North by Northwest” scene when writing this post. I haven’t seen “Saboteur” yet, but I watched a clip with the Statue of Liberty scene on YouTube.

What a great, rich topic! I’ve honestly never thought of these two monuments as art, but of course they are. We learn about them in school as national monuments, as part of American history, not as works of art, but of course they’re both. I’m going to Mt. Rushmore next week, and I’m sure that I’ll see it quite differently now. Thanks for the links — and the reminder about North by Northwest!

Hi Karen! Thanks for your comment. I wonder if you will view Mt. Rushmore in a different light, given the conversation on this post. I’ve never seen the monument myself. If you have any art-related observations when you are at Mt. Rushmore, feel free to share them here.

Got to Mt Rushmore at about 8:15am, so crowds were light, though the Sturgis motorcycle rally was going on nearby, so there were some bikers, and some families. Even without a huge number of tourists, I still had a hard time seeing it as anything but a national monument. I was glad to have read a little bit about it before going, but even so, it didn’t really make me think of anything else art-related. I did think about the fact that it was largely made with well-timed, precise dynamite blasts, which is pretty amazing. For me, though, it was more about history, less about art.

Hi Karen! Thanks for sharing your experience. It’s interesting to hear about how you were compelled to view the monument as a piece of history instead of a work of art. I wonder if the physical distance between the tourists and the actual sculpture hinders people from appreciating Mount Rushmore as a work of art? From what I gather, the viewing platform is still quite far away from the mountainside, right?

Anyhow, thanks for sharing! One day I’ll hope to go and visit Mount Rushmore myself.

Personally, I view the president’s faces as sort of overdone and carving them in stone, albeit a monumental task at this scale/in a mountain, is very institutional .

Their faces are everywhere. Growing up they are on posters in elementary schools for students to memorize. They are on the coins and bills we keep in out pockets and never take two seconds to look at. And you can go to Washington DC or history book and see more sculptures/images.

I saw Mt. Rushmore when I was 14 and I was wayyy more interested in the mountain goats that were hopping around than the faces. I think the whole monumentalizing part of this work takes away from the fact that it is a piece of art. If they just left it carved and sans the amphitheater and state pillars it would be more museum like and more like mountain carving “graffiti”. (Which would be a very cool concept.)

But it is pretty straight forward and unimaginative. Faces, carved in stone just at a large scale. Now I do think talent does play a role in the execution of the piece but I don’t know how far it goes when there is no telling you did it. If Picasso did it you would know because it was done by Picasso or if François Pompon you could tell by the style who did it. Not saying that you have to have a certain style to be known.

There is something to be said for realism but you run the risk of being, especially with these common images of getting lost in the masses and these images left unaltered by style or medium are just kind of ehhh.

Hi Kelsey! Thanks for your comment! You’ve brought up some good points. I think that the ubiquitous nature of Mount Rushmore images (along with other iconic works, like the Statue of Liberty of even the “Mona Lisa”) causes people to forget that these objects are works of art.

I also think that you have an interesting idea about removing the amphitheater and pillars. I’ve never been to the monument, but it seems like the removal of those features might encourage one to have a different interpretation of the work of art. Perhaps the amphitheater and pillars also make the site seem more “touristy” than “artsy.”

I think that Borglum has a very conservative style, which I think ties into what you are saying about the distinct style of individual artists (like Picasso or Pompon). Perhaps if there were more identifiable (or radical) stylistic characteristics, then viewers would be encouraged to look at this piece differently. The art world seems to privilege artists who have distinct and radical styles.