Thursday, September 3rd, 2020

Josiah McElheny’s “From an Historical Anecdote About Fashion”

I haven’t been blogging on here this summer, but that is not to say that I haven’t been busy or thinking about art. The pandemic has forced me to spend the summer prepping online material for the three classes that I will be teaching this Fall quarter. I’ve been thinking about art every day, as I record lecture videos while seated at my desk. I’ve often chuckled at my bizarre sense of fashion during this videos, which is a professional look from the waist up, but a casual look from the waist down with flip flops or exercise pants hidden from the camera’s view.

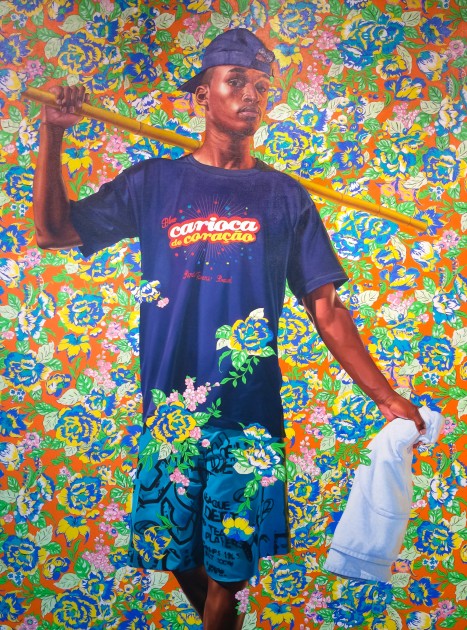

Josiah McElheny, “From An Historical Anecdote About Fashion,” 2000. Blown glass objects and display case, overall: 67 7/8 × 120 × 27 5/16in. (172.4 × 304.8 × 69.4 cm). Whitney Museum of Art

Perhaps in some ways that’s why I have been drawn to Josiah McElheny’s “From an Historical Anecdote About Fashion” during this pandemic. I miss having a reason to get dressed up in fancy clothes, and I miss having the free time to watch films from the Golden Age of Hollywood. McElheny explains in an ART:21 documentary (at 40:38 in this video) that he was looking to draw parallels with “the connection between a glass factory and the designs of Christian Dior.”

The “historical anecdote” that served as inspiration for McElheny was regarding the 1952 Venice Biennale. That year, the glass design company owned by Paolo Venini entered a display of vases that were based off of the haute couture fashions which Ginette Gagnous Venini, the owner’s wife, wore when she visited the factory.2 Ginette was very involved in the business and was said to have been seen by those in the furnace room whenever she ascended or descended the stairs to and from the office.

Josiah McElheny, detail from “From An Historical Anecdote About Fashion,” 2000. Blown glass objects and display case, overall: 67 7/8 × 120 × 27 5/16in. (172.4 × 304.8 × 69.4 cm). Whitney Museum of Art

Josiah McElheny, detail from “From An Historical Anecdote About Fashion,” 2000. Blown glass objects and display case, overall: 67 7/8 × 120 × 27 5/16in. (172.4 × 304.8 × 69.4 cm). Whitney Museum of Art

McElheny’s clothes give off a definite sense of 1950s fashion, especially with the wasp waists and several voluminous skirts. The excessive use of fabric in Dior “New Look” line drew a contrast with the restricted use of fabrics during the World War era.1 And so maybe now, in a time when I feel more restricted in my behavior, these voluminous dresses seem like an excessive and unattainable luxury.

Another thing that I love about McElheny’s pieces is that they suggest the female form that would be wearing the clothing. The glass objects give off a sense of presence and absence, since the figures’ forms are visible through the clothing but also conspicuously lack any anatomical features outside of the dresses themselves. Likewise, the translucent glass seems present and also absent. Perhaps that’s why I’m drawn to these works of art as I’m working to create an online class: I’m constructing a virtual “presence” for myself while also keenly aware of how I am absent from the physical classroom. Or perhaps I’m also drawn to the fragility of the glass medium, since the pandemic has caused me to think more about the fragility of human life and health. All depressing thoughts aside, I wish that quarantine and online teaching could be as carefree and elegant as these references to haute couture!

1 Robin Updike, “Fashion and Glass Merge With Imagination In Show At Henry,” Seattle Times (March 17, 1999). Available online: https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=19990317&slug=2949785

2 The idea of designing a bottle to look like a dress wasn’t completely new to the Vanini factory. In 1947 a design was produced for Venini which decorated bottles with lace, to suggest the body of a woman or a mannequin in 19th-century dress. See Marino Barovier and Carla Sonego, eds., Paolo Venini and His Furnace, Skira Editore (2016), pp. 83-84. Available online: http://www.showonshow.com/skira/2017/venini/pressdocs/PVenini_layout_UK.pdf