Friday, June 19th, 2015

“A History of the World” Snippets

For the past few months, I have been listening to podcasts of A History of the World in 100 Objects while I exercise. The clips are engaging and interesting, and they provide some distraction for me while I run. I’ve learned and pondered a lot of things in the process, and I wanted to write down a few snippets of things that have stood out of me in the various episodes I have heard.

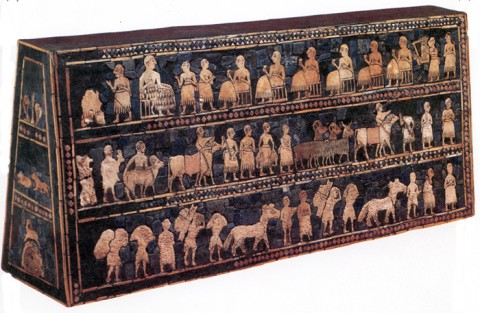

The Standard of Ur: I first learned about the Standard of Ur when I was in high school, I think. But I’ve never thought much about the size of this object. Neil MacGregor describes this as “the size of a small briefcase” which looks “almost like a giant bar of Toblerone.”1

I’ve never realized that this famous object was so small! Since it has the nickname of a “standard,” I just assumed that it was a larger size. I also was interested to learn that the inlaid stone and shell come from various locations: Afghanistan (lapis lazuli), India (red marble), and shell (the Gulf).2 These various mediums indicate that the Sumerians had an extensive trade network.

If you are interested in learning more about the Standard of Ur and theories surrounding its original function, see HERE.

Head of Augustus: I enjoyed learning about this head because it reminded me of discussions that I hold with my students about how ancient art was/is mutilated and stolen in times of war. This statue is no different. It once was part of a complete statue that was on the border of modern Egypt and Sudan. However, an army from the Sudanese kingdom of Meroë invaded this area in 25 BC (led by “the fierce one-eyed queen Candace”), and this army took the statue back to Meroë.3 The head was buried beneath a temple that was dedicated to this particular Sudanese victory, which meant that every person walking up the stairs to the temple would insult the emperor by stepping on his head.4 Even today, sand of the African desert is visible on the sculpture.

The David Vases: I begin listening to this episode without any prior knowledge of these vases, so I was surprised to learn that these were from China (I assumed when reading the episode title that the vases had some nude figure which depicted the biblical David, à la Michelangelo or Donatello.) Nope! These Chinese vases are named after their most famous owner, Sir Percival David.

The thing that is most interesting to me is that, since these vases are dated 13 May 1351, we know that this level of fine quality blue-and-white porcelain predates the Ming dynasty (the dynasty from 1358-1644, which is typically associated with fine blue and white porcelain). In fact, we also know that the blue and white tradition is not Chinese in origin, but Middle Eastern! Neil MacGregor explains how Chinese potters used Iranian blue pigment cobalt (which was known in China as huihui qing – “Muslim blue”).5 Interestingly, Chinese artists even used Iranian blue pigment for exports sent to the Middle East, to meet the Iranian demand for blue and white ware after the Mongol invasion destroyed pottery industries in the area.6 It’s interesting to me that Iranian blue traveled to China, only to travel back to its area of origin as export pottery decoration.

Sainte-Chapelle and the Crown of Thorns: This chapel was not featured in the podcast specifically, but it was discussed at length in the episode for the Holy Thorn Reliquary. Sainte-Chapelle is a church that was built basically to be a reliquary, to house the Crown of Thorns. Surprisingly, the Crown of Thorns cost more than three times the amount paid to build Sainte-Chapelle!7 Today the Crown of Thorns is housed in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris; it was moved there by Napoleon in the 19th century.

I was particularly intrigued by the discussion of the Crown of Thorns coming to Paris, and I wanted to learn more on my own. Louis IX dressed in a simple tunic (without royal robes) and walked through the streets barefoot while he carried the relic. The barefoot king is depicted in the Relics of the Passion window in Sainte-Chapelle. I also learned through my own research that the Crown of Thorns, while on its way to Paris, was housed in a cathedral in Sens overnight. This moment was honored in a window from Tours, which depicts Louis IX holding the thorns on a chalice.

The other thing I found interesting about the arrival of the Crown of Thorns is that this elevated the status of France among the Christian countries of Europe. “When the crown arrived, it was described as being on deposit with the king of France until the Day of Judgment, when Christ would return to collect it and the kingdom of France would become the kingdom of heaven.”8

Are there any episodes/chapters from A Short History of the World in 100 Objects that you particularly enjoy? Please share!

1 Neil MacGregor, A History of the World in 100 Objects (New York: Penguin Group, 2011), p. 72.

2 Ibid., 72-73.

3 Ibid., 225

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid, 413.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid., 425. Sainte-Chapelle cost 40,000 livres to build. The Crown of Thorns was bought from the Venetians for 135,000 livres (400 kilograms of gold). MacGregor writes that The Crown of Thorns was “probably the most valuable thing in Europe at the time.”

8 Ibid., 427.