Monday, June 1st, 2015

Carpet Pages and Islamic Prayer Rugs

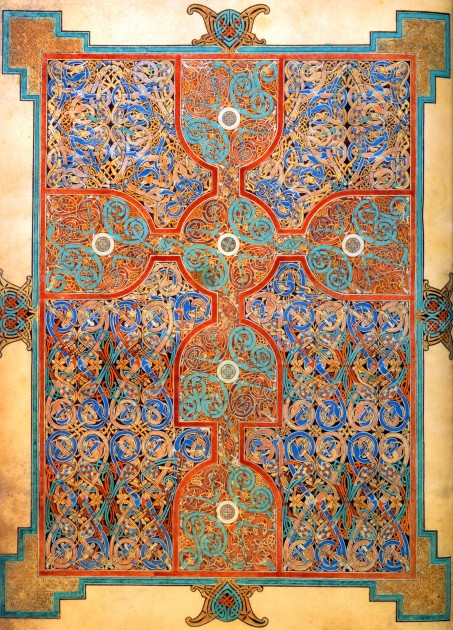

Carpet Page from the Book of Kells, folio 33r, c. 800. Painted illumination on vellum. Image courtesy Wikipedia

This morning, in preparation for class, I was looking at a digital copy of the Book of Kells. I previously have written about how I think it is important to consider the exuberant decoration of the Chi-Rho-Iota page (known as the “Incarnation” page, folio 34r) in relation to the accompanying joyful text, which announces the birth of Christ. As I was looking at the digital copy of the book further, it struck me how this design is significant in relation to the context of the Book of Kells itself, since the Chi-Rho-Iota page is directly preceded by a carpet page (see above).

Carpet pages (sometimes called “cross-carpet pages”) are illuminated manuscripts which have a design that is generally in the shape of a rectangle (filling the outline of the page itself), with interlace and decorative geometric forms woven within the general rectangular form. Such pages appear in Christian, Islamic, and Jewish illuminated manuscripts. Usually, there is hardly any text on these pages, or no text at all. The designs of these manuscripts usually are quite symmetrical and typically have a strong vertical axis (and sometimes horizontal axes as well, which often forms the shape of a cross). There are several possible origins for this type of carpet design, but I am drawn to the idea that these “carpets” are reminiscent of Islamic prayer rugs, for I think they may have also had a similar function: these carpets can serve as an aid to meditation in the sense that they alert the reader that the subsequent Gospel text is important, and the reader should mentally prepare before looking at the following pages within the book or codex.1

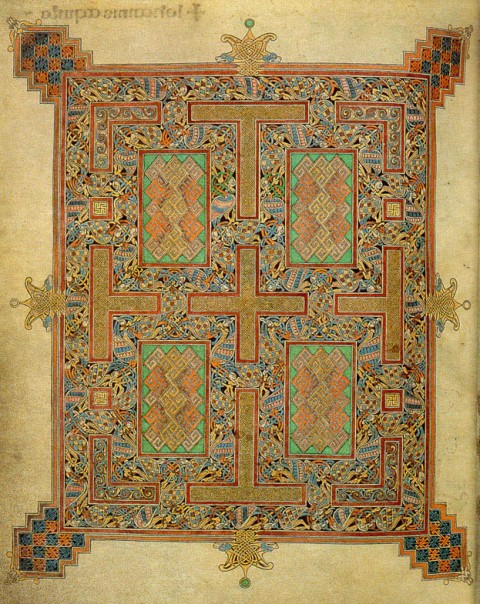

To see the relationship between carpet pages and other pages in the text, consider how the carpet page from the Book of Matthew in the Lindisfarne Gospels precedes the incipit page (see image of these two pages HERE). This is a really complex and gorgeous carpet page (see below), which includes snake-like creatures whose mouths clamp down on their own writhing bodies (see this image detail).

Here are some of my other favorite carpet pages:

Do you have any favorite carpet pages? If you know of any other connections between carpet pages and Islamic prayer rugs, please share! I did find an abstract for a lecture that explored the possibility of how illuminated Islamic manuscripts may have factored into the production of physical carpets themselves, although these historical connections are still unclear.

1 Other origins for carpet pages include contemporary metalwork, Coptic manuscripts, and Roman floor mosaics in post-Roman Britain. See Robert G. Calkins, Illuminated Manuscripts of the Middle Ages (Cornell University Press, 1983), p. 53.

This may be a bit of a stretch, but the carpet pages also remind me of buddhist mandalas. A kind of representation of the macrocosm, with the four corners of the earth. I also wonder about any numerical significance of the decorations, but that may also just be my affinity for numerical symbolism.

ps. you are awesome.

I’d say there are definitely connections between Muslim prayer rugs and Christian carpet pages. I wonder if you could link the artists of these pages to people who went to the Middle East during the Crusades?

Michelle Brown has done a lot of work recently on the connection between carpet pages and prayer rugs, in her 2003 and 2011 books on the Lindisfarne Gospels (the latter drawing heavily on the former), and a bit in her book on manuscript illumination. Hourihane touches on the discussion in his entry on Carpet Pages in The Grove Encyclopedia of Med. Art and Architecture.

The British Isles had extensive connections with the east through trade and missionary work–this shows up in manuscript decoration and other material objects, like coins. Irish and Anglo-Saxon monks also used prayer rugs that were a lot like Islamic prayer rugs; I presume that the influence could have flowed both directions.

Perfect! Thanks for pointing out Michelle Brown’s work, Zillah. I also didn’t know that monks had actual prayer rugs which looked like Islamic prayer rugs. Fascinating! I haven’t found any pictures of such actual rugs yet, but I’ll look into Michelle Brown’s writings to discover more.

I love that you are reminded of mandalas, Phin. I don’t know if there is a connection, but I do think there are some similarities with geometric abstraction and a general interest in symmetry.

It would be interesting if we could connect specific artists to the Middle East. The examples I show in this post pre-date the Crusades, but trade and missionary work are viable possibilities for cross-cultural influence. I know that Eadfrith of Lindisfarne was the artist and scribe responsible for the Lindisfarne Gospels, and perhaps scholar Michelle Brown has made some connections between Eadfrith and the Middle East.

The link to 7th century Armenian carpet weaving is lavishly illustrated in The Christian Oriental Carpet by Volkmar Gantzhorn, published by Taschen. Reissued under title Oriental Carpets.

He explains the influence of hand woven pile woven within the matrix of the wrap and weft strings on a hand loom. The geometric patterns passing into the hand painted carpet pages of Celtic manuscripts.

Early Anglo-Saxon Christian scholarship was influenced by two men that might be relevant to this issue: Theodore of Tarsus (who had studied in Syria and is said to have also shown evidence of interactions with Persia), and Hadrian (aka Adrian) who was a Berber originally from North Africa.

Theodore and Hadrian established a school in Canterbury, providing instruction in both Greek and Latin, resulting in a “golden age” of Anglo-Saxon scholarship.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_of_Tarsus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adrian_of_Canterbury

I am wondering if they may have brought a style or taste in manuscript decoration to England that was melded with the Celtic style.