Sunday, January 19th, 2014

Pregnancy in Western Art

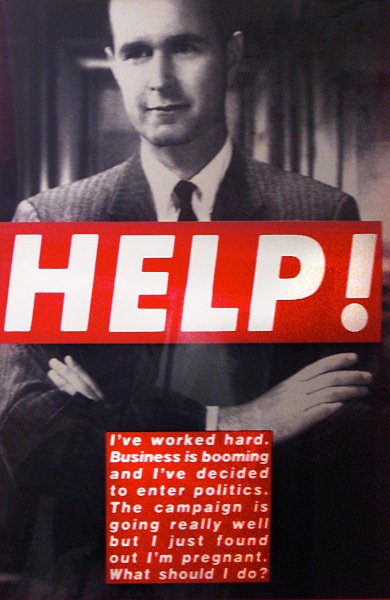

Earlier this week, I was researching something on Barbara Kruger when I happened upon some posters that she made in 1991 for bus shelters, as part of a project created through the Public Arts Fund. These posters, which had the word “HELP!” superimposed over the picture of a man, used smaller blurbs of text to draw attention to issues that people might face when they become pregnant. To me, Kruger is pointing out that any difficulties surrounding pregnancy should not be merely perceived as a “woman’s problem,” but a situation which affects both genders. These posters are discussed elsewhere in relation to social responsibility and abortion, which I think also is appropriate.

In this instance, I think Kruger’s depiction of a male, while addressing the topic of pregnancy, is entirely appropriate. However, these posters also made me pause and think about how there are comparatively few representations of pregnant women in the Western canon as a whole, especially, say, in contrast with the popularity of the idealized female nude. The topics of pregnancy and childbirth are found in the narratives and historical circumstances surrounding works of art (I’m particularly thinking of Christian scenes of the Visitation and Nativity), but many of those works of art do not highlight the pregnant or postpartum female body. I suppose on one hand, this makes sense, because the pregnant form was not part of the idealized form found in classical art (which is a primary foundation for the Western canon). I thought I would compile a few images of pregnant women in this post — either well-known objects or obscure ones made by a well-known Western artist — as a starting point to think about this topic:

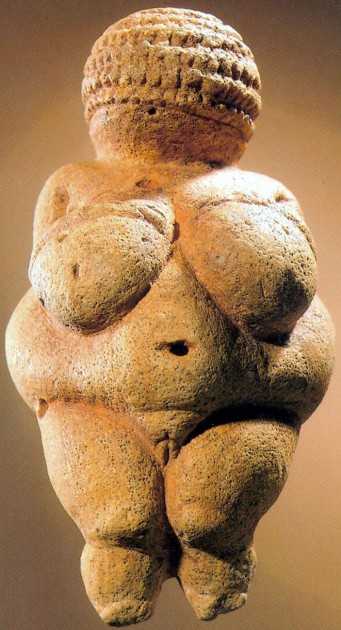

The so-called "Venus of Willendorf" (also 'Woman of Willendorf), ca. 28,000-25,000 BCE. Oolitic limestone, 4.25" inches (10.8 cm)

I thought the Venus of Willendorf would be a good place to start this compilation, particularly due to relatively recent findings by McCoid and McDermott that this statuette and other Paleolithic “Venus” figurines are representations of pregnant women. It is thought that these statues may have been made by prehistoric women who were looking down at their own bodies, which could explain for some of the extreme exaggerations of the body and the lack of feet.1

I like this Northern Renaissance example of the Visitation (see above), because Elizabeth and Mary are not only decidedly pregnant, but they are laying their hands on each other’s bellies (which visually draws attention to their pregnant forms).

Perhaps the Northern tradition of painting (with its keen interest in Aristotelian, empirical observation) caused artists like van der Weyden and Rubens to depict the pregnant form more clearly. In Rubens’s “Visitation” scene, Mary is decidedly pregnant. (It is hard to tell whether Elizabeth is pregnant, due to her placement and dark clothing, however.) I also wonder if Rubens, who had a preference for depicting the curvaceous female form, might have visually been drawn to the curves of the pregnant belly in this instance.

I haven’t come across many images of Southern (especially Italian) artists who painted the pregnant female form, but I do like “La Donna Gravida” by Raphael. I especially like how the sitter also draws attention to her pregnant belly with her hand.

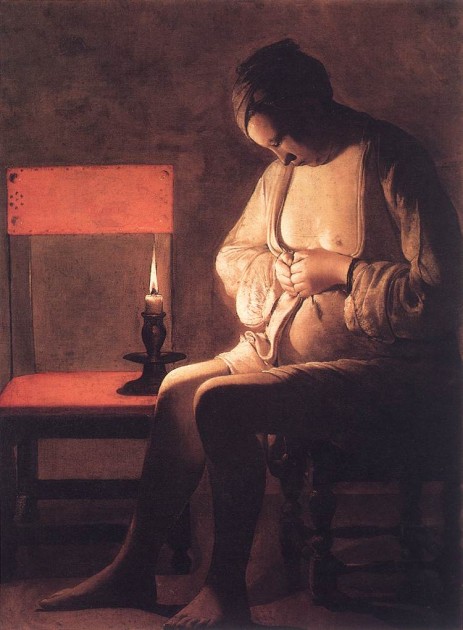

This painting by Georges de la Tour depicts a woman who is crushing a flea between her fingers. The seemingly everyday subject matter probably has deeper symbolic meaning, however. It has been suggested that this is a depiction of the Virgin (perhaps isolated after Joseph discovers she is pregnant), with the candle representing Christ as the Light of the World.

If we jump to the contemporary art scene, there are some images of pregnant women that exist. It makes sense that more pregnant forms would pop up in the postmodern era, since artists are questioning and drawing awareness to traditional Western standards. I think that Ron Mueck’s hyperrealistic Pregnant Woman is probably the best image that highlights and respects the pregnant form. Mueck studied a pregnant model, starting in the sixth month of her pregnancy until about the time that she gave birth. Mueck also studied anatomical books and drawings diligently while creating this sculpture, in order to achieve accuracy.

I really like art historian Mary Kisler’s discussion of this piece, who mentions how this sculpture, in a public environment, has parallels with how a pregnant woman’s body becomes public in actuality. To prove her point, Kisler discusses how people (even strangers!) will sometimes touch the belly of a pregnant woman, when the non-pregnant female has stricter, more private boundaries.

I have to admit, apart from Mueck’s work, I’m not entirely smitten with several of the other contemporary representations of pregnant women. For example, consider this monumental statue by Marc Quinn:

Marc Quinn, "Alison Lapper Pregnant," 2005, 12 feet (3.6 m) high. Photo courtesy of Garry Knight via Flickr under Creative Commons license.*

This sculpture by Marc Quinn was placed in Trafalgar Square in 2005. It depicts the artist Alison Lapper, who was born without arms, when she was eight months pregnant. On one hand, I like that Quinn is trying to deconstruct Western notions of beauty by depicting a figure who is different from Western ideals. So, in that sense, I think that this sculpture is empowering to women, pregnant women, and any figure type which traditionally has been excluded from canonical standards. On the other hand, though, I feel like Quinn is using the pregnant form to get his point across – almost as if the pregnancy itself is a mere device for “shock value.” In this sense, I have a hard time viewing this sculpture as a pure celebration of the pregnant female form.

I also feel the same way about Damien Hirst’s sculpture, Verity, which is a variant of earlier works of art by Hirst (like The Virgin Mother). One half of the statue shows the exterior of the pregnant woman, while the other half shows the internal organs and matter inside the woman, including the fetus.

Verity is a monumental statue which is placed on the pier of Ilfracombe, Devon. Hirst, who lives in Ilfracombe, has loaned the sculpture to the town for twenty years (beginning in 2012). Hirst views his sculpture as an allegory for truth and justice, and I think that meaning is made clear with the revealed anatomy on one side. However, like with the Quinn sculpture, I feel like this sculpture is using the pregnant form to generate “shock value,” rather than for concrete symbolism or celebration of the pregnant form itself. It seems like the reference to truth and justice are best expressed in the sword and scales; I can’t see Hirst’s immediate connection between pregnancy and truth or justice. (If anyone can make that direct connection, please share!)

Do you have a favorite representation of the pregnant form in art? Any further thoughts as to why the pregnant form is comparatively scarce in Western art as a whole, apart from what I have put forward about idealized figures?

1 McCoid and McDermott, “Toward Decolonizing Gender: Female

Vision in the Upper Paleolithic,” in American Anthropologist 98 (no. 2): 319-

326.

*See Creative Commons license for photograph by Garry Knight