Monday, February 27th, 2012

“Invisible Women: Forgotten Artists of Florence” by Jane Fortune

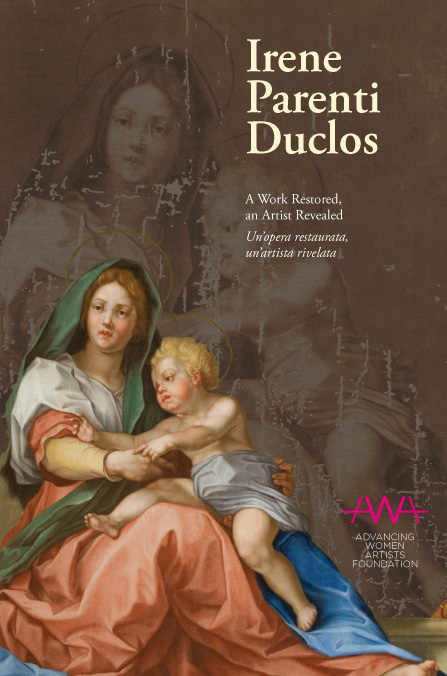

I recently have had the pleasure of reading Jane Fortune’s book, Invisible Women: Forgotten Artists of Florence. The next time I visit Florence, I want to take this book with me! Jane Fortune explores some of the lesser-known female artists, whose works are located in some of the great galleries and institutions (and their storage vaults, unfortunately) in Florence. In addition to discussing the lives of these artists, the book aims to introduce the reader to the restoration and rediscovery of unknown or famous works by women artists.

Invisible Women is divided into very short chapters that are dedicated to a particular artist, or a short theme (like the restoration for a work of art). However, even though the chapters are short, they provide a wealth of information about female artists who lived between the 15th and 20th centuries. I was continually surprised at learning new facts and information about these female artists, even though some have long been familiar to me. I also was pleased to see how the book included a range of artistic techniques and traditions, including those of Dutch and French artists.

To give somewhat of a sense of the book, I thought that I would write down some short facts that I learned while reading the book (loosely similar to how Fortune presents different artists in short chapters):

- Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Le Brun (self-portrait shown above) painted no less than 600 portraits (and her oeuvre is about 800 works). Her rise to become the court painter for France is very impressive, considering that Vigée-Le Brun was primarily self-taught by copying the masters (p. 73). It has been remarked that the woman depicted on the left side of Vigée-Le Brun self-portrait resembles Marie Antoinette, Vigée-Le Brun most famous subject.

- Angelica Kauffmann was conned into marrying a man who fraudulently posed as a count from Sweden. Given her friendship and connection with the painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, Kauffmann was able to avoid the social stigma of separation. Years later, after her charlatan-cum-husband passed away, was Kauffmann free to marry again. She married the Venetian painter Antonio Zucchi (p. 77).

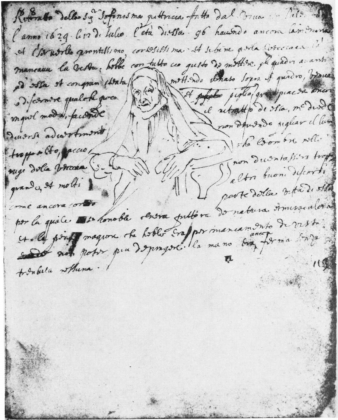

- Maria Van Oosterwyck (shown above) weaseled out of a marriage proposal to fellow floral painter Wilhelm Van Aelst. Maria originally accepted the proposal with a few conditions. The marriage could take place after the following: 1) Van Aelst needed to work for one year, working 10 hours days at his studio and 2) Van Aelst could not display his affections for Maria at any time. At the end of the year, Maria “cunningly refused his proposal, showing him her ticks for the times he had failed to maintain his part of their pact” (p. 93).

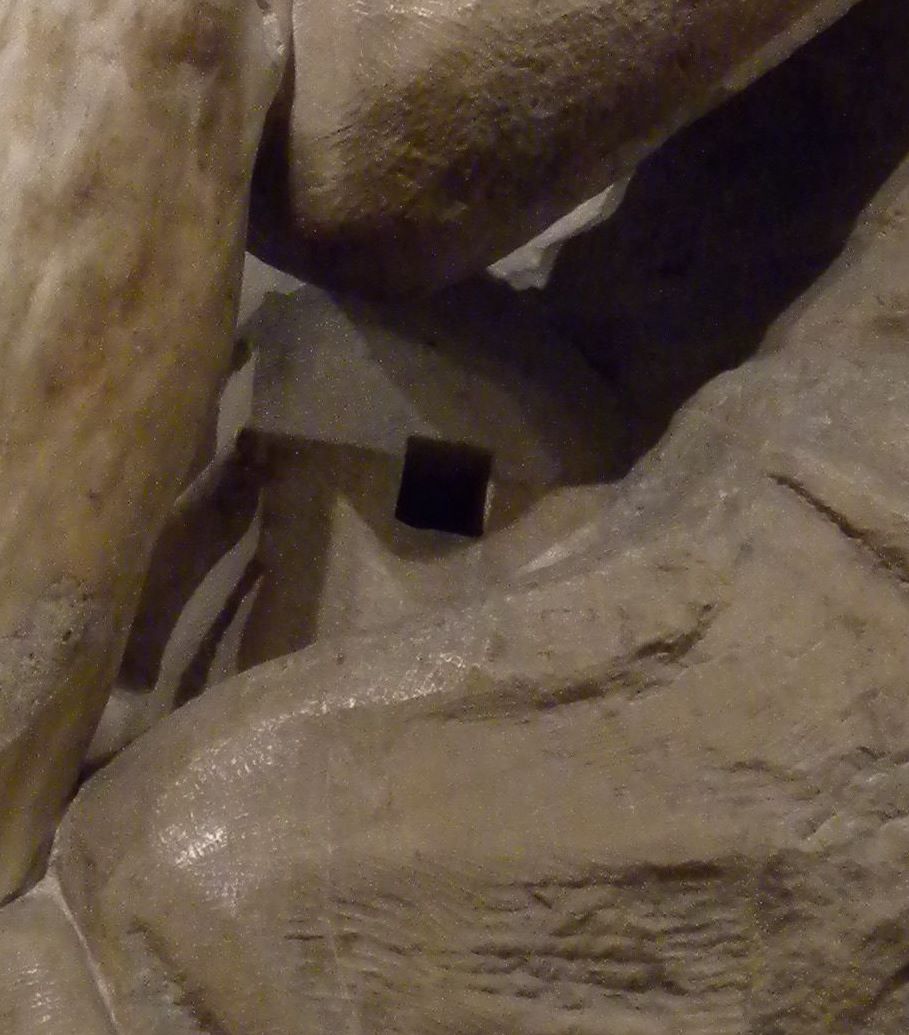

- Near the end of her life, Sofonisba Anguissola was the tutor to the 24-year old Flemish painter, Anthony Van Dyck. Anguissola was losing her eyesight (possibly due to cataracts), but still continued to advise Van Dyck on his painting technique. Later, Van Dyck remarked “that he had learned more from a sightless old woman than from all the master painters in Italy” (p. 146).

- Artemisia Gentileschi didn’t learn to read or write until she was an adult (p. 157).

- Artemisia Gentileschi was commissioned to make a painting (one of the first in the cycle of 15) to commemorate the life of Michelangelo. The Allegory of the Inclination (c. 1615-1616) is part of the Casa Buonarroti collection.

I noticed that Jane Fortune focused her book on artists who made two-dimensional art (like paintings or pastels). This made me wonder about female sculptresses who worked in Italy (such as Properzia de’ Rossi) between the 16th and 20th centuries. Would there be enough information to write another book on sculptresses (whose works are in Florence or elsewhere in Italy)? Painting and drawing seem to have been a more popular and accessible activities for women during that time, but perhaps I only make that assumption because there isn’t much written information about sculptresses.

Anyhow, this book was very interesting and fun. The chapters are written in a warm, approachable tone which compliments the beautiful color reproductions. The book is written in both English and Italian, so it has appeal to a broader audience. The other great thing about this book is that is provides “The Women Artists’ Trail Map” at the end of the chapters, so that a visitor to Florence can easily locate paintings by female artists that are currently on public view. Isn’t that neat?

I would highly recommend this book to anyone who is interested in art or women artists. The proceeds from Invisible Women goes to support projects funded by the Advancing Women Artists Foundation and the Florence Committee of National Museum of Women in the Arts. What great causes!

Thank you to Linda Falcone and The Florentine Press for the review copy of this book.