Wednesday, May 8th, 2013

Museum “Shrines” and Performative Rituals

The quarter is progressing along, and now I am covering a new book with my students: New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. It’s been really fun to delve into some of the museum theory that I studied several years ago as a graduate student and graduate fellow at a small art museum.

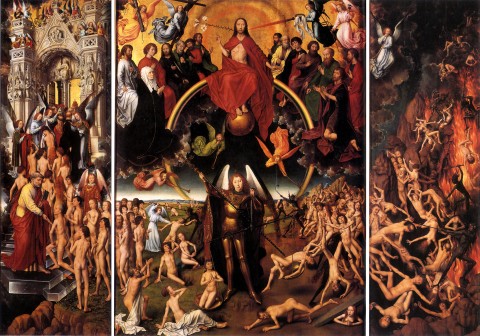

The introduction of this text explores several of the metaphors that are commonly used to describe museums. One of the most interesting metaphors for me is the “museum as shrine.” Museums have a quasi-religious environment, and I like how Janet Marstine explains this idea:

“The museum as shrine is a ritual site influenced by church, palace, and ancient temple architecture. Processional pathways, which may include monumental staircases, dramatic lighting, picturesque views, and ornamental niches, create a performative experience. Art historian Carol Duncan explains, ‘I see the totality of the museum as a stage setting that prompts visitors to enact a performance of some kind, whether or not actual visitors would describe it as such.’ Preziosi adds, ‘all museums stage their collected and preserved relics . . . Museums . . . use theatrical effects to enhance belief in the historicity of the objects they collect.”1

This description immediately made me think of the architecture in several museums which encourage performative, theatrical, and even ritualistic actions from the visitor. The first space that came to mind was the Grand Staircase at the Louvre, above which the “Nike of Samothrace” presides (see photo above). Here are some other spaces which I considered:

The Seattle Art Museum has a “processional way” staircase in the older part of their museum. Although these stairs are no longer used on a regular basis, there are escalators in the main museum area which carry the visitor to higher physical (and suggestively “spiritual”) levels. Even with an escalator (which doesn’t require much physical movement on part of the viewer), I think that this motion still contains an element of performance on the part of the viewer. Also, shrine-like picturesque views are found at the Seattle Art Museum Sculpture Garden; the structure of this building is created largely out of glass walls.

The Centre Pompidou probably has the most famous set of museum escalators. The way that the “tubes” slowly climb with alternating sections of flat and angled lines remind me of the terraces of ziggurats from the ancient Near East.

The ramp in the interior of the Guggenheim is probably one of the best examples of ritualistic art, I think because the viewer is continually aware of his or her ascent in relation to the rest of the museum space. The winding ramp reminds me of spires for religious buildings, even contemporary structures like the Independence Temple for the Community of Christ in Missouri.

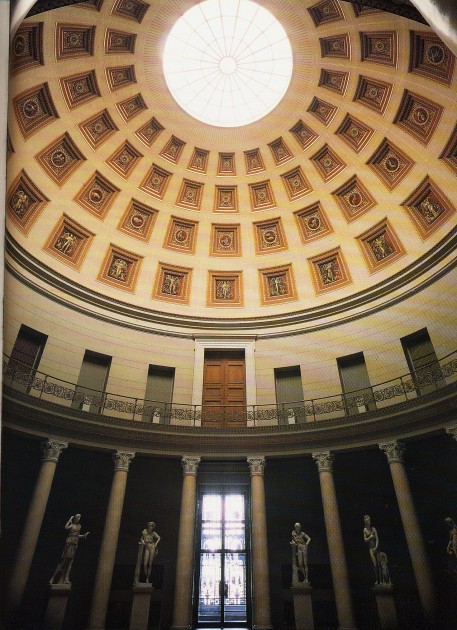

Schinkel, View of the staircase (and view overlooking the Pleasure Garden) in the Altes Museum, Berlin (19th century). Image courtesy of Wikipedia

I think that the Rotunda of the Altes Museum evokes this shrine-like setting (and performative nature) not only by evoking classical imagery (this is a small version of the Pantheon), but also creating a stage-like setting for the sculptures, separating them either with niches or columns. The sculptures on the bottom level are also elevated onto stage-like plinths.

Last week, my students and I discussed whether today’s museums should try to bring more self-awareness to their designs and displays, in order to perhaps expose or at least recognize the “shrine-ness” of the institution. We wondered what visitors might think if a museum was blatantly decorated like a shrine (with candles around works of art, offerings scattered in front of displays, etc.). Would viewers feel uncomfortable if they knew they were taking part in a ritual at a museum? What do you think?

What are some of the other shrine-like aspects of museums? Can you think of any museums which encourage some type of “performative” or ritualistic-like activity on part of the viewer? In a general sense, I think that the quiet whispers that are expected in many museums can fit with this idea.

1 Janet Marstine, “Introduction” in New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introdution by Janet Marstine, ed. (Blackwell Publishing, 2006. See also C. Duncan, Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), pp. 1-2. See also D. Preziosi and C. Farago, Grasping the World: The Idea of the Museum (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), p. 13-21.