Last week I met a woman who told me about her trip to Rome. Before learning that I am an art historian, this woman explained to me that she loved her trip to Italy because she didn’t go to any museums. (You can imagine my surprise – I spend most of my time in museums when I travel!) Instead, this women and her husband spent the whole trip relaxing and eating delicious Italian food.

While listening to this woman, I couldn’t help but think in my head, “Why would you want to have your whole vacation revolve around something as transient as food? Once you eat the food, it’s gone.” But as I thought about our conversation afterward, I realized that experiences with art are just as transient. (And really, aren’t vacations based on the premise of transience as well?) A person’s physical interaction with a work of art, especially in a museum space, is limited by time. And as much as we “consume” either art, or food, or any experience, we are only left with the memory of that interaction afterward. Perhaps that’s why reproductions of art are so popular in museum gift shops: people want to try and recreate (or remember) their fleeting interaction with a certain work of art.

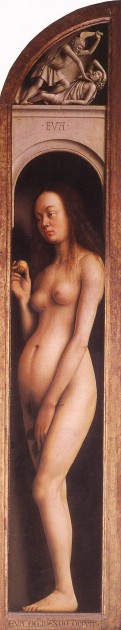

A visitor looking at gilt-framed paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

As I’ve been thinking about this idea of transience and art, I’ve realized how much art (especially historical and academic art) tries to disguise or resist this transient nature by emphasizing mass and physical bulk. Historical paintings are traditionally placed in heavy gilt frames. For centuries, paintings were prized if they were painted on a grand, monumental scale. Sculptures are often weighty too, traditionally made in heavy mediums like marble or bronze. It’s almost as if art wants to assert its physical presence as much as possible, so that the viewer won’t realize that his/her interaction with the object will later become a memory. Perhaps historical pieces also want to assert their physicality in order to make their subject matter seem less-distant to the contemporary viewer, too.

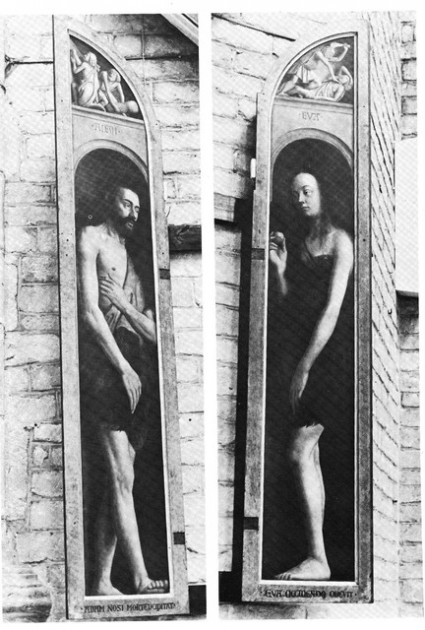

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty, first built April 1970 (as seen in March 2003)

Although all physical interactions with art are transient and finite on some level, I do think that art from the 20th and 21st century is less deceiving when it comes to transience. Many modern and contemporary artists embrace the idea of transience, and even highlight that feature within their piece. I’m particularly reminded of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty in the Great Salt Lake, which is supposed to interact and change with the environment over time. It’s easy to see the transient nature of the Spiral Jetty when comparing my photograph (shown above, which was taken in 2003) with a 1970 film still of the piece.

My college friends at the Spiral Jetty in March 2003

I remember in 2002 there was a lot of hype about the Spiral Jetty, because it was visible for the first time in several years. The spiral was above water level for almost a year, so in March 2003 some friends and I decided to make a trip and see the piece for ourselves. I remember being struck with how the earthwork appeared really “ghostly” – just a shadow of the 1,500 foot-long spiral I had seen in my art history textbooks. Despite the sheer size of the piece, the salt-encrusted rocks traced a rather whimsical outline in the water. The work of art seemed transient, just like I remember this experience at the Great Salt Lake as transient (especially when I look at this photo and think of the time that has passed since I went on this trip with my friends).

It’s interesting to contrast the once-bulky Spiral Jetty with the large, gilt-framed paintings and historical statues in an art museum. For me, the Spiral Jetty brought about more awareness of myself (as a viewer) and of the physical time that I was spending with the piece. Perhaps I also had more awareness of transience (and the passing of time) because I was able to physically touch and interact with the Spiral Jetty, too. And I think that even the setting (nature vs. a timeless museum space) can affect the viewer’s awareness of their transient experience with a work of art.

Although a work of art (and the experience with a work of art) can make a different impression on each viewer, it is a little bit depressing for me to realize that physical experiences with visual art are not made to last forever. There comes a point when any viewer of art needs to walk away, close their eyes, or simply just blink. But luckily, even though physical moments with works of art are finite in terms of time, we can have multiple experiences with the same work of art. Perhaps the multiplicity of transient experiences leads to something somewhat lasting and permanent in the human mind?