Thursday, April 21st, 2022

Van Eyck Brothers as “Just Judges”

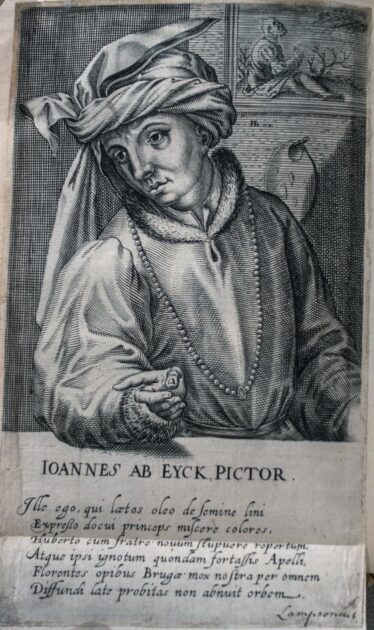

Earlier this week I discovered a new(ish) Smarthistory video about Karel Van Mander, an early 17th-century biographer of painters who is sometimes referred to as the “Northern Vasari.” The video spends some time featuring a print which depicts the painter Jan Van Eyck. This portrait appeared in Van Mander’s publication Het Schilderboeck.

Karel van Mander, Het Schilder-Boeck (Haarlem: Paschier van Wesbusch, 1604), first edition in two volumes with added illustrations, 21 x 16.7 x 5.8 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Image courtesy of Steven Zucker and Smarthistory via Fickr.

The video reports at 3:33 that this portrait is based off of Van Eyck’s painting Man with the Red Turban, but I don’t think that I agree. Karel Van Mander’s own account of Jan Van Eyck clearly describes a self-portrait of the artist that is nestled among the Just Judges panel of the Ghent altarpiece. It would make sense that the portrait in Van Mander’s publication would match Van Mander’s own description. Also, it is clear when comparing these two portraits that they are similar in composition, not just due to the angle of the heads but also the angles of the turban folds and the inclusion of rosary beads.

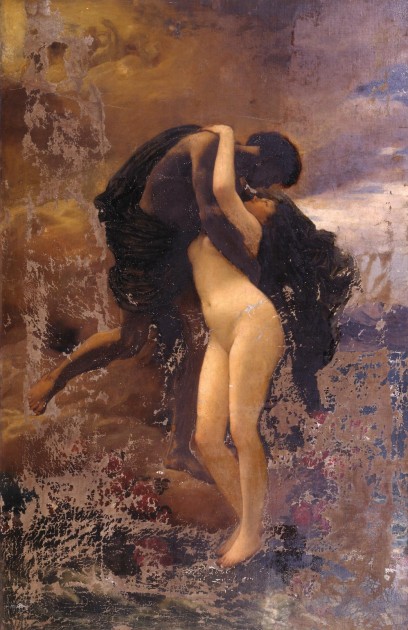

Jef Van der Veken’s modern copy after Jan Van Eyck’s “Just Judges” panel, from the Ghent altarpiece, original from 1432.

Van Mander’s description of the self-portrait is nestled among descriptions of panels of the Ghent altarpiece. Van Mander explains that the two Van Eyck brothers who worked on this altarpiece, Hubert and Jan, are both depicted in the Just Judges panel (the panel on the lower left of the open altarpiece). The description by Van Mander, translated into English, is as follows:

On the other panels are figures on horseback…the two painters, Hubert and Jan. Hubert sits on the right-hand side of his brother in accordance with his seniority; he looks, compared to his brother, quite old. On his head he wears a strange hat with a raised, turned-back brim at the front of precious fur. Jan wears a very ingenious hat, something like a turban which hangs down from behind; and over a black tabard he wears a red rosary with a medal.1

If we follow Van Mander’s description, then Hubert is likely the figure in profile view, who is at the right of Jan Van Eyck. I don’t think Hubert was pinpointed to be the figure immediately next to Jan. A photograph of the original, now-lost Just Judges panel shows that figure was partially covered up with the “precious fur” that Van Mander described. The modern copyist, Jef Van der Veken, ended up reducing the size of the fur brim, as can be seen in this comparison:

Photograph of Van Eyck’s original Just Judges panel vs Van der Veken’s copy of the Just Judges panel. Image via Catchlight blog

If Van Mander is correct, this panel is extra special because it contained depictions of not only the two Van Eyck brothers, but possibly other notable people too (Van Mander mentions a “Count of Flanders” and other speculations abound as to the identity of the figures). Perhaps it isn’t surprising, then, that this was the panel that was stolen in 1934 and never recovered. If you are interested in reading more about this stolen panel, I recommend Noah Charney’s book Stealing the Mystic Lamb (which I have discussed in a previous post).

1 Karel Van Mander, Het Schilderboeck, Haarlem, 1406. English translation Eric Fernie’s Art History and its Methods (London: Phaidon Press, 1995), p. 51.