Monday, February 21st, 2022

Ansel Adams, Structure, and Music

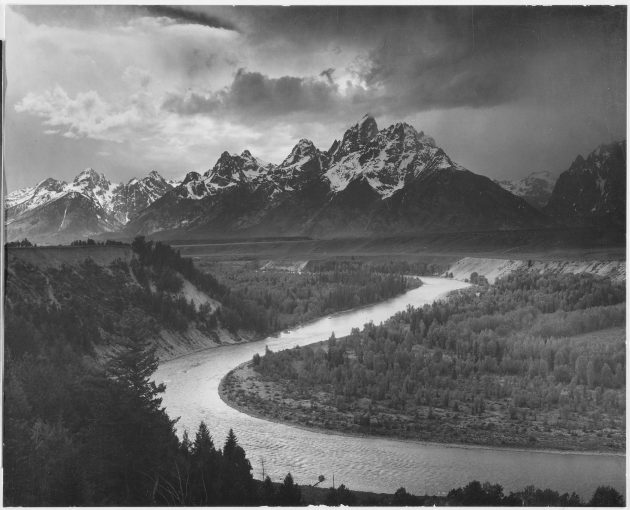

Ansel Adams. The Tetons and the Snake River, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. 1942. Image via Wikipedia, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration

Earlier last week, I taught my students about Ansel Adams’s photography. In preparation for our class discussion, I watched this documentary on Ansel Adams from the Master Photographers series (1980). I learned while watching that Adams had trained to become a concert pianist but ultimately decided to become a photographer.

It was interesting to hear him discuss photography in comparison to music. In explaining the range of light and dark contrasts in his photographs, he made an interesting comparison to the piano and its division into octaves:

“It’s like the piano, you have 88 keys, you can go from the lowest to the highest, or you usually work within a few octaves. Oh there were some magnificent things, but they were just an octave or two” (10:35-10:49).

If Adams likes the structure provided by the piano as a tool for making music, then it makes sense to me that he would like the structure provided by the technology of photography and the camera as a device. This interest in structure also extends to how he perceives his photographic shots as a type of framework that is akin to a musical score. In this same interview, he said, “I’m guilty of creating a cliché which I use very often, because in actuality the negatives are like the composer’s score. All of the information is there. And then the print is the performance, see. So you interpret the score at the varying aesthetic emotional levels, but never far enough away to violate the essential concept” (13:23-13:48).

Even Adams’s own musical tastes tend toward those which have structure. In a 1984 interview with Milton Esterow, Adams agreed with how Esterow’s observation of how Adams has a preference for composers with a large structure, such as Beethoven, Bach, Chopin and Scriabin. Adams continued and said, “Yes, there’s some evidence of precision and structure, nothing amorphous. I don’t react to Debussy.”

Learning about Adams and his relationship to music has made me think of his black-and-white photographs in a new way. I’m reminded of the black and white colors that are used for piano keys, or the the black and white used for a printed musical score. The shiny gloss his photographs makes me think if the shine of grand piano or the elegant “concert black” attire at a classical performance. Even this 1958 short film of Adams playing the piano is in black and white, which complements his work so well. So now, even though Adams’s best-known photographs are those which depict the great outdoors, I like thinking about how his photographs can also remind me of something metaphysical and intangible, like music, or the indoor spaces of a symphonic hall.