Saturday, July 14th, 2012

The Farnese Hercules and Renaissance “Substitutions”

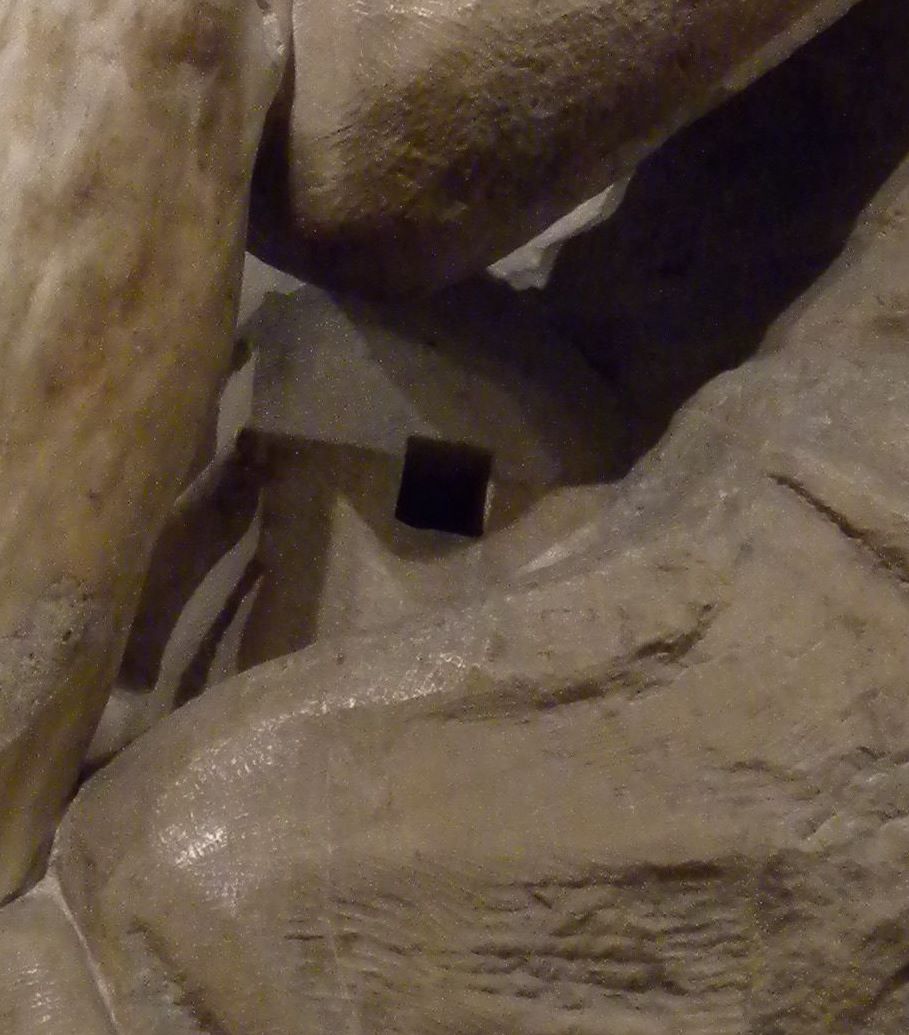

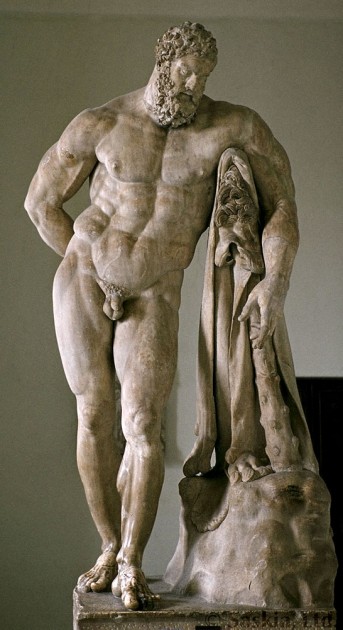

Farnese Hercules (also known as the "Weary Hercules"), 3rd century CE. Roman copy by Glykon after the 4th century BC bronze original by Lysippos. Height approximately 10.4 feet (3.17 meters).

This past week my research meandered into Roman art and the Farnese Hercules. This Roman statue was excavated in various pieces from the Baths of Caracalla during the Renaissance period, in 1546. The legs, however, weren’t found during the early excavations. Before the original legs were discovered, the Renaissance sculptor Guglielmo della Porta provided other legs for the piece. And although the original legs were found not long after, della Porta’s legs were still kept with the statue until 1787, when the originals were finally put into place!1

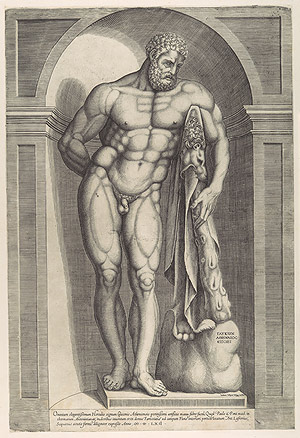

Apparently, Michelangelo advised that della Porta’s legs be retained with the original statue, in part to prove that modern sculptors could compare with those from antiquity.2 I think this is interesting, given that Michelangelo had already been involved in a longstanding debate with Bandinelli regarding the original composition of the Laocoön. Michelangelo obviously wanted to respect the original composition of classical statues, but it seems like he didn’t necessarily care if the original marble took part in the composition. Perhaps Michelangelo also wanted to promote Guglielmo della Porta, who was his protégé. Anyhow, Michelangelo obviously found that della Porta’s legs were acceptable, although some slight differences can be observed in the position of the feet (see below).

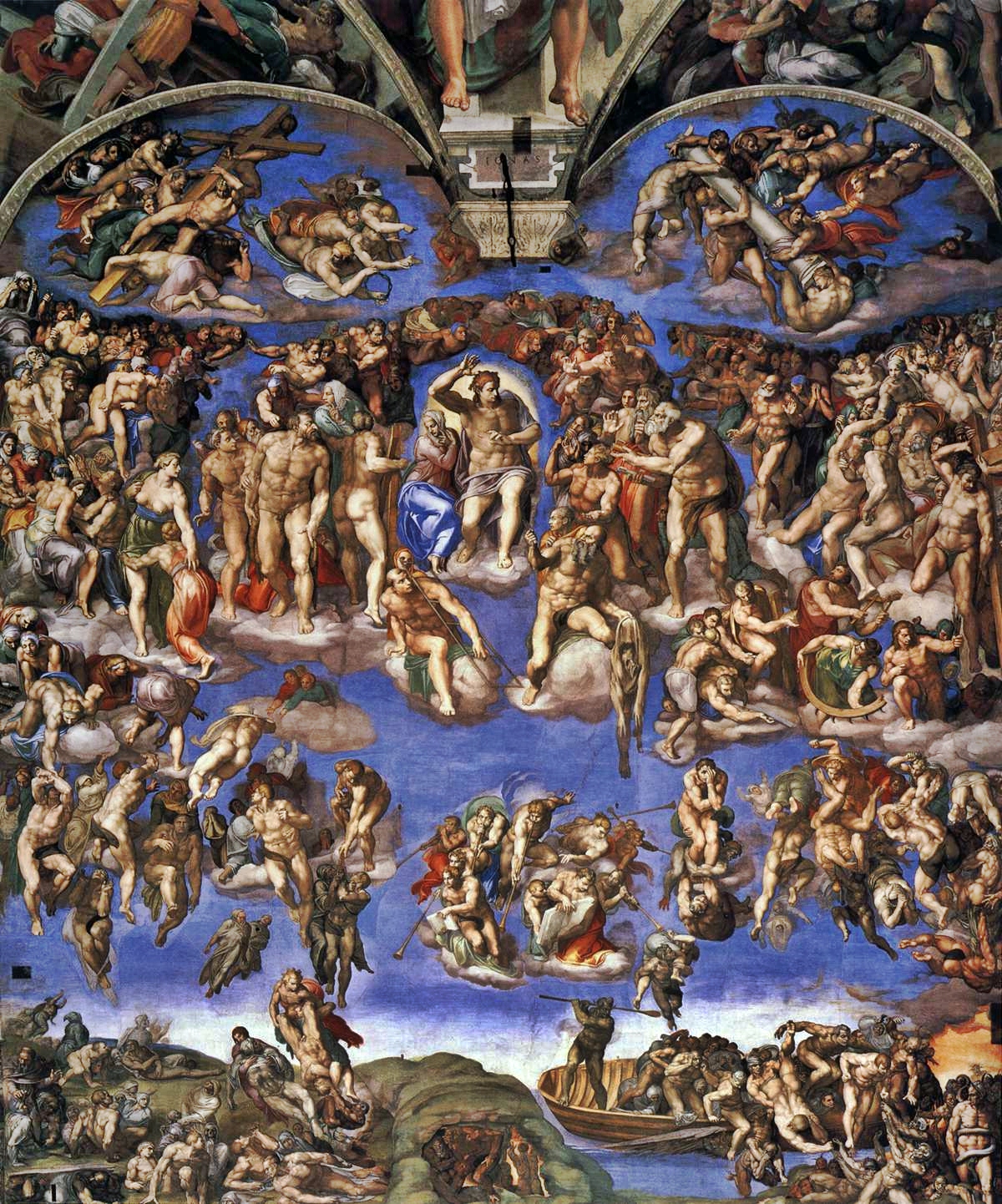

Jocob Bos, Farnese Hercules, 1562. Engraving. Michelangelo designed the niche in which the Farnese Hercules was placed.

After the original legs were finally reunited with the sculpture in 1787, Goethe recorded that he saw the Farnese Hercules in his Italian Journey (1786-1788, German: Italienische Reise). Goethe criticized della Porta’s “substitute” legs, and felt that the installation of the original legs made the sculpture “one of the most perfect works of antiquity.”3

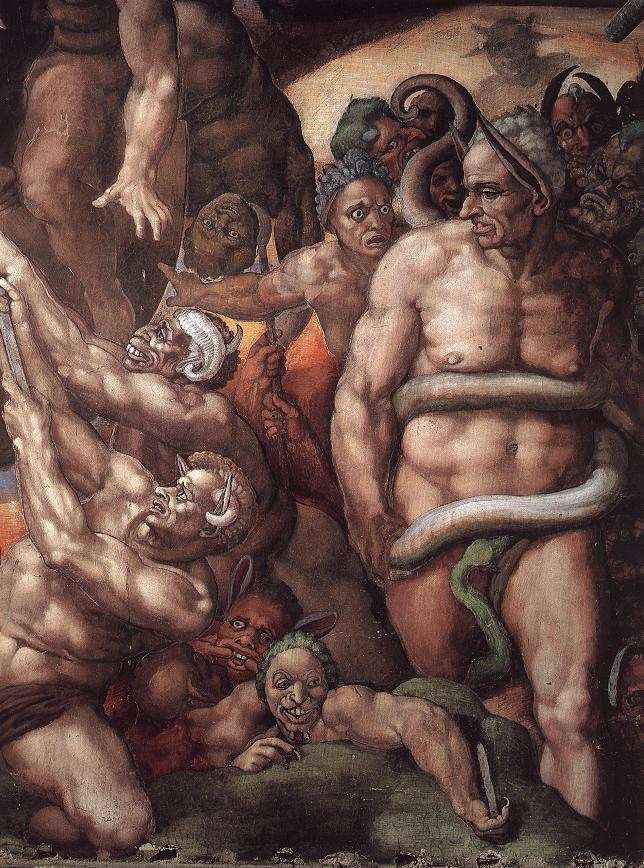

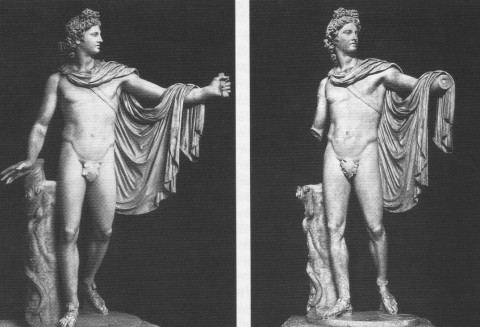

Of course, the Farnese Hercules isn’t the only piece of classical art which was “restored” during the Renaissance period. Although it seems like della Porta’s legs functioned as an adequate substitute for many, I’ll admit that there are other Renaissance “restorations” which seem a bit awkward to me. Perhaps I’m just used to the missing limbs of the “Apollo Belvedere,” but I think that the Renaissance additions on this statue aren’t completely graceful, especially Apollo’s hands and fingers.

Left: "Apollo Belvedere" (2nd century AD) as restored in the 1530s. The left hand, right forearm, and fig leaf were added at the request of Pope Paul IV. Right: "Apollo Belvedere" as restored after WWII. The Renaissance additions were removed, with the exception of the fig leaf. Today, the fig leaf has been removed, but it appears that the Vatican currently displays a restored version of the statue that is similar to the Renaissance restoration. If anyone has information on when this most recent restoration took place, I would love to know!

When considering the post-WWII restoration of the “Apollo Belvedere” (in which the Renaissance additions were removed), Jas Elsner wrote that “whether the modern concern to return such marbles to their ‘authentic’ form constitutes an improvement is, and will remain, a moot point.”4 I’m up for discussion, and I’d like to see what people think about “improvements” and “authenticity.” Do you have any thoughts on the substitutions and “restorations” of Greco-Roman sculpture that took place during the Renaissance? Is it better to only leave original material on these works of art? Should we make conclusions about later “restorations” on a sculpture-to-sculpture basis, depending on the nature and quality of the addition/substitution? (And if so, does that mean that we value aesthetics and our opinion of quality more than original history?)

I feel like these are tough questions for me; I fluctuate between both camps. I am a sucker for original context and original works of art, but I do think that sometimes a substitution can help to recreate the original context in some form. If della Porta didn’t create substitute legs for the Farnese Hercules, the monumental height and overwhelming effect of that sculpture would have been lost (until, of course, the original legs were found). On the other hand, I also think it’s important to realize that the works of art have their own history, even beyond the period in which they were created. Sometimes I like having a visual reminder that specific works of art held importance during the Renaissance.

1 Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500-1900 (New Haven:Yale University Press, 1981), 229.

2 Ibid. See also Jan Todd, “The History of Cardinal Farnese’s ‘Weary Hercules,” in Iron Game History (August 2005): 30. Todd citation can be read HERE.

3 Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey (Penguin Classics, 1970), p. 346. Citation can be read HERE.

4 Jas Elsner, Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 16.