Tuesday, May 21st, 2013

A Timeline of Early Modern Censorship

Masaccio, The Expulsion of Adam and Eve, 1424-25. Image on right shows the fresco after its restoration in the 1980s, which removed the fig leaves that were added in the 17th century. Image courtesy Wikipedia

A few weeks ago I was contacted by an art magazine, specifically requesting information on nudity and censorship in the history of art (since I had previously written on this topic). It took me a few hours to compile the necessary information for this group. Unfortunately, I never received any response after sending a detailed email to my contact, so I assume that the information I sent will not be used in the final article or timeline about censorship. Instead, I have decided to publish my research here.

Although the following timeline is not complete by any means, I think that these are some of the most significant and interesting events which surround the issues of censorship and nudity for the Early Modern period in Western art.

- c. 1504: Objections arose regarding the nudity of Michelangelo’s “David” (to the point that people threw stones at the statue). It is reported that a skirt of copper leaves was created to cover the statue at one point, although we don’t have a mention of this skirt by Vasari (see some commentary on this problematic story HERE). Art historian Paul Barolsky explains that Michelangelo’s “rival Pietro Arentino specifically called [the sculpture’s genitals] ‘the indecency of the colossus.’ In a more positive way, [biographer] Vasari points towards the statue’s erotic zone when he praise the figure’s ‘very divine flanks.’ The ‘fianchi,’ flanks or hips, enframe that region of the body which is the center of what Arentino refers to as the sculpture’s ‘impudicità” or lewdness.”

- Around 1541: Cardinal Carafa and Monsignor Sernini (Ambassador of Mantua) work to have Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” censored, due to the nudity. This undertaking is known as the beginning of the “Fig Leaf Campaign.”

- 1547: In Spain, the first edition of the Index of Prohibited Books (written in 1547, published in 1551) does not mention nudity specifically, but condemns “all pictures and figures disrespectful to religion” (my emphasis).

- 1555-1559: Pope Paul IV undertakes censorship of nude works of art, which includes the castration of ancient statues.¹

- 1563 (December 3-4): 25th session of the Council of Trent (as part of the Catholic Counter-Reformation) specifies that art should avoid lasciviousness, “in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust.”

- 1565: Daniele da Volterra (later known as “Il Braghettone” or “The Breeches Painter”) was hired to paint bits of drapery over the nude figures of Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment. These “breeches” by Volterra were the first; other bits of drapery were added to this fresco in the following centuries.

- 1592 – Clement VII undertakes a personal inspection of Rome to ensure that revealing sculptures, including semi-nude depictions of Christ on the cross, are covered with drapery.

- 1644 – 1655: Pope Innocent X had phalluses chiseled off of Roman sculptures in the Vatican. Metal fig leaves were placed on the figures instead.

- About 1680: Fig leaves were added to the bodies of Masaccio’s Adam and Eve figures in the Brancacci Chapel (see image above). These were removed in the 1980s, when the frescoes were cleaned and restored.

- 1758-1759: Pope Clement XIII covers more sculptures at the Vatican with fig leaves

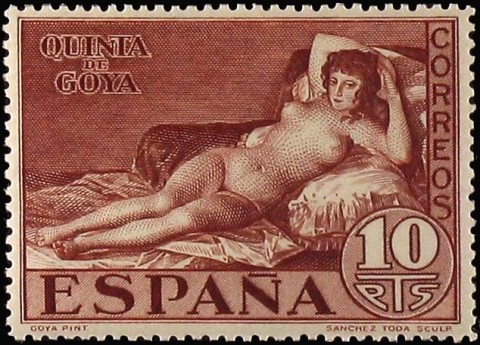

Spanish stamp from 1930, based off of Goya’s painting “La Maja Desnuda,” c. 1797-1800. Image courtesty Wikipedia

- About 1797-1800: Goya paints “La Maja Desnuda” (sometimes called “The Naked Maja”) which is among one of the first works of Western art to depict a woman with visible pubic hair. In 1815, Goya was summoned before the Spanish Inquisition to discuss this painting. “La Maja Desnuda” was turned into a stamp in the 1930s by the Spanish government, but the US Postal service would not deliver incoming letters that were marked with this stamp. One source reports that the US Postal service ruling was reversed as late as 1996!

- About 1803: Goya paints “La Maja Vestida” (“The Clothed Maja”), which is a painting of the same woman who posed for “La Maja Desnuda.” It could be that this painting was created in order to be more acceptable than the previous version.

- 1846-1878: Pope Pius IX places fig leaves on more statues at the Vatican.

- 1878-1903: Leo XIII places fig leaves on more statues at the Vatican.

- 19th century: Modifications were made to Bronzino’s “Allegory of Venus and Cupid” (discussed in detail HERE).

Large fig leaf covering the plaster cast of Michelangelo’s “David” in the Victoria and Albert Museum

- About 1857: Large fig leaf is created for the plaster cast of Michelangelo’s “David” which is located at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

- 1865 – Victor Lagye creates copies of Adam and Eve for the Ghent altarpiece by Jan van Eyck, with the figures clothed. These copies were placed in the altarpiece.

- Between 1981-1994: Some (but not all) of the “breeches” of Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” fresco are removed during restoration and cleaning of the chapel. Others are not removed because the painting could have been damaged in the process.

Censorship in regards to nudity really begins to end in the late 19th century. The early twentieth century sees a lot of nude sculptures that are also more provocative and sexual in nature.

Can you think of any other significant dates in regards to nudity and censorship? I stuck with the Early Modern period in my timeline, but we could also go back to ancient period (I’m reminded of when Early Christians destroyed nude sculptures of the Parthenon in the 5th century CE.)

If you are interested in learning more about censorship and nudity, I would recommend watching this documentary: “Fig Leaf: The Biggest Cover Up in History.”

1 Art historian Leo Steinberg explained that we don’t know a lot about the specific censorship actions taken by Pope Paul IV. He writes, “But we are not well informed about the chronology of these practices. Montaigne (Essays, III, 5) cites ‘many beautiful and antique statues’ which were being ‘castrated’ in Rome during his youth by order of ‘that good man,’ meaning Pope Paul IV (1555-1559).” See Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014) p. 186. This book is a reprint of Steinberg’s original 1983 publication. Citation online HERE.