Monday, August 10th, 2015

Book Review and Giveaway: “The Art of the Con” by Anthony M. Amore

This is certainly the summer for new publications on art crime – and the summer isn’t even over yet! When I learned that Anthony M. Amore wrote a new book called The Art of the Con, I was in the middle of reading another recently-published book on art forgery by Noah Charney. I was curious to see if Amore’s book would be similar in content to Charney’s fantastic book.

For the most part, there wasn’t too much overlap between the content of Charney and Amore’s books. Both authors do discuss the forger Wolfgang Beltracci, but Amore goes into more detail in his book. (Amore dedicates essentially a whole chapter to Beltracci, whereas Charney dedicates a few pages to Beltracci within his broader discussion how forgery relates to different types of crime schemes.) Amore also elaborated on a lot of art cons and schemes that were unfamiliar to me, so I found a lot of the subject matter to be new and riveting.

Before reading this book, I was already familiar with Amore’s previous publication, Stealing Rembrandts (see my review HERE). Like Stealing Rembrandts, this new book The Art of the Con is an engaging read. I quickly read this book within a matter of days, not only because the subject matter was interesting to me, but because Amore’s writing style is accessible and entertaining. My critiques of this book are very minor: there were a handful of sentences in which pronouns were used in a confusing way, and I also disagreed with Amore mentioning that Cezanne was a Cubist (although the artist influenced Cubism, I would say that most art historians typically refer to Cezanne as a Post-Impressionist).1

All in all, I recommend this book to anyone who is interested in art crime, particularly in connection with scams relating to the buying and selling of art. I want to highlight a few things from this book which were of interest to me:

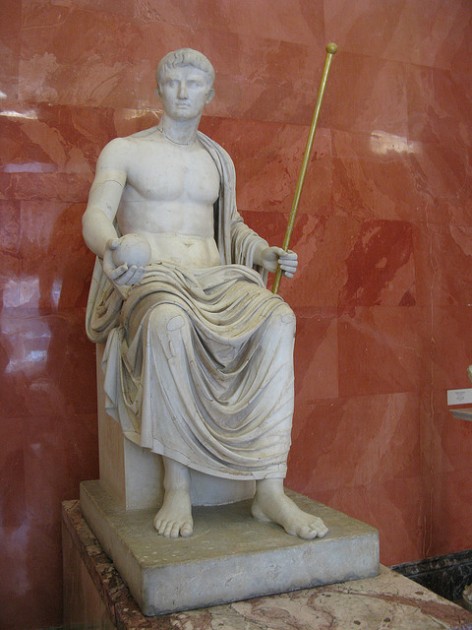

Caravaggio (?) or Circle of Caravaggio, “Apollo the Lute Player,” c. 1597. Private Collection, USA (Ex-Badminton copy). Image courtesy Wikipedia

Since I own a copy of Clovis Whitfield’s book Caravaggio’s Eye, I was interested to learn in Amore’s book about how Whitfield worked to curate a show, Caravaggio, with another art dealer named Larry Salander. The centerpiece of the show was a painting called Apollo the Lute Player (shown above), which Whitfield and Salander believed to be an autograph version by Caravaggio.2 In fact, Salander appraised the painting at $100 million, which was about one thousand times its previous sale price of $110,000!3 However, due to Salander’s unethical and criminal behavior in the art market scene, which Amore explores in detail, Whitfield ended up pulling this star component of the exhibition on the afternoon of the show’s opening! Despite Whitfield’s apparent lack of involvement in Salander’s misdoings, the show never mounted as originally planned (although some pictures were shown elsewhere), which led the Telegraph to call the exhibition, “The Star Show that Never Was.”

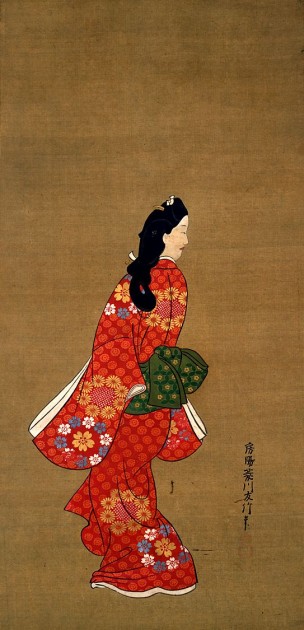

Amore mentions in his book about how the Seattle Art Museum was involved in a law suit in 1998, in which the museum which sued the Knoedler Gallery in New York. The museum, in turn, was being sued by the heirs of the Jewish art dealer Paul Rosenberg. The Seattle Art Museum had received Matisse’s Oriental Woman Seated on Floor (Odalisque) (shown above) as a gift from Prentice and Virginia Bloedel. The Bloedels had bought the painting from the Knoedler Gallery about forty years before donating the painting to the SAM. However, the Knoedler gallery gave false information to the Bloedels about the provenance of the painting, failing to admit that the painting had been looted from Paul Rosenberg during the Nazi era.4 After returning the painting to the Rosenberg family, I know that the SAM and Knoedler Gallery settled out of court: I’m inclined to think that the gallery gave cash to the museum, since the other option from the agreement was to give the SAM one or more works from the Knoedler inventory, and I currently can’t find any mention of the Knoedler Gallery in the online collection.5

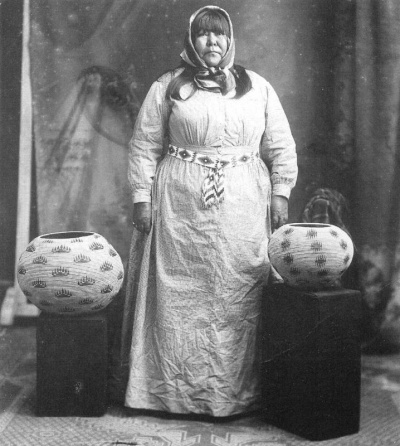

Glass art falsely purported to be by Dale Chihuly, as sold by Michael Little. Image via U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement.

Amore dedicates a chapter of his book to dealing with the art con and fraud which takes place online. I was intrigued by the story of Michael Little, a man from Renton, Washington, who purported to sell works by Dale Chihuly on eBay (one example of such fraudulent glassware is shown above). Even after eBay pulled Little’s listings after being alerted to the fraud, Little continued to sell the fraudulent glassware online, in person, and through a Renton auction house! One collector was swindled out of thousands of dollars, after he bought pieces that he intended to donate to Gonzaga University’s Jundt Art Museum.6 Little was sentenced to only five months in prison. I later found out, after finishing Amore’s book, that the judge sentencing Little commented that he wished he could also order Little to attend basic training in the Army!

I’ve learned a lot from reading The Art of the Con. I’m very glad that I read this book, and I’ll be sure to continue to use it as a resource in the future. I’m happy to announce that I can share this book with someone else, too! One lucky reader can win a free copy of this book! Local and international readers are equally encouraged to enter. I will be randomly selecting one winner (using this site) on August 17, 2015. So you have seven days to enter this giveaway! You can enter your name up to three times. Here are the ways you can enter:

1) Leave a comment on this post!

2) Tweet about the giveaway (be sure to include my Twitter name: @albertis_window in your tweet, so I can find it).

3) Write about this giveaway on your own blog or website, and then include the URL in a comment on this post.

Thanks to St. Martin’s Press for generously providing a review copy and giveaway copy of The Art of the Con.

1 For Cezanne reference, see Anthony M. Amore, The Art of the Con (New York: Palgrave MacMillan Trade, 2015), 114.

2 Ibid., 64-65. Other scholars contest Whitfield’s findings that the painting is autograph. For one example, see footnote 3 in Florian Thalmann, Irony, Ambiguity, and Musical Experience in Caravaggio’s Musical Paintings (University of Minnesota, 2013), p. 4.

3 Ibid., 64, 66.

4 Ibid., 54.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid., 214.