Saturday, May 17th, 2014

East and West: The Edo Period in Japan and the Baroque Period in Europe

Due to my involvement as a volunteer at a local art museum, I’ve been learning and thinking a lot about non-Western art lately. I feel really incompetent when it comes to the Asian and African art – especially in terms of building historical context – so I feel a little out of my comfort zone. I’m excited to learn more about these artistic traditions, though.

In order for me to better contextualize and understand these new historical and artistic periods, I try to mentally cross-list each non-Western period with what is happening contemporaneously in European history. It also has been helpful for me to learn about ways that the Westerners interacted with these different cultures, so I can understand each country and time better within its history at large. So far, I feel like I have been able to best remember things that happen during the Edo Period of Japan (1603-1868), because that period coincides with the Baroque period (as well as Romanticism, Neoclassicism, and Realism). It’s been fun for me to find parallels with Baroque art and the early Edo period.

One parallel that I have found between the early Edo period and the Baroque style is the interest in light. The cultural and artistic approaches to light, however, are quite different. In the Baroque period, light was used as an illusionistic painting in order to create drama through tenebrism. Artists created sculptures and architecture which utilized natural light in order to create dramatic visual contrasts of areas which were brightly lit and cast in shadow.

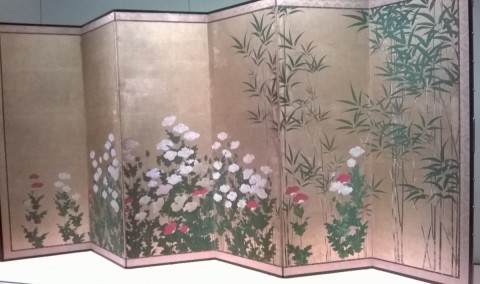

Kano Shigenobou, “Bamboo and Poppies,” early 17th century. Pair or six-panel screens; ink, color and gold on paper. Seattle Art Museum

In the Edo period, the interest in light was quite different and practical. Due to the introduction of Western of firearms in Japan in the 16th century, the Japanese began to build fortress palaces with thick walls.1 The interiors of these fortress palaces was very dark, especially in contrast to the airy, filtered light which permeated through the paper walls of their previous palaces. The Japanese favored indoor screens that were decorated with gold in order to better illuminate the interiors of their new, darkened fortresses. A few examples of such screens are the Shigenobou screen shown above, the Shigenobou screen “Wheat, Poppies, and Bamboo” at the Kimbell Art Museum, as well as the Crow Screen at the Seattle Art Museum. The reflective gold surface provided more light, but I think the gold also is visually dramatic and stunning too, which makes a nice connection with the Baroque style in Europe. In fact, even the flat gold background has some parallel with the dark or ochre monochromatic backgrounds that are found in Caravaggesque paintings.

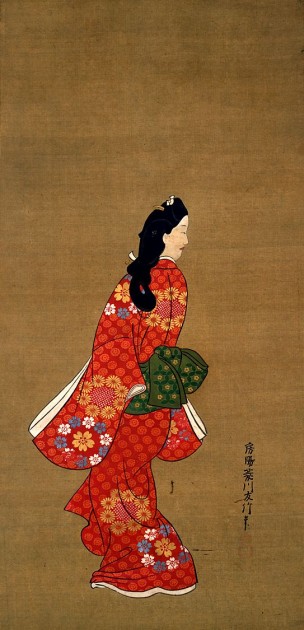

The popularity of woodblock prints during the Edo period also is easy for me to remember, due to some parallels with what happens in the West at the same time. During the Edo period, wealthy Japanese merchants could afford to have art, particularly prints. The widespread accessibility of art reminds me a bit of the wealthy middle class and rise of the open art market in Holland during the 17th century. In Japan, a wealthy merchant might decide to purchase a print of a famous geisha or actor. Such subject matter is found in Ukiyo-e prints (“pictures of the floating world”), which were popular between the 17th and the 19th centuries. The artist Hishikawa Moronobu is one of the earliest to have made these types of prints in the 17th century (see one such example above). The accessibility of woodblock prints continued to rise in the subsequent century; technological advancements enabled the printing of multiple colors on a single sheet in 1765.

Do you know of other chronological or artistic parallels between Western and non-Western artistic periods? I’m familiar with chinoiserie and japonisme from a Western perspective, for example – this time I’m trying to make parallels to help me specifically remember points about Asian or African art.

1 “SAMART: Golden Screens of the Kano School,” SAMBLOG of the Seattle Art Museum, accessed May 15, 2014, http://samblog.seattleartmuseum.org/2011/11/samart-golden-screens-of-the-kano-school/

I wrote a paper on how Japanese art influenced the art of the American West in grad school. It’s actually a lot more influential in the US than people realize.

I don’t know anything about Japanese art or its phases, but that last picture of Beauty Looking Back has some Baroque traits – a sense of movement, the contraposto posture, less formal and less static.

All I can think of was the explosion of popularity Japanese art found in Belle Époque France. The bright color, composition, and strong lines of the 17th century woodblock print you show remind me a lot of lithographs seen in France at the turn of the century.

Thanks for your comment, Val! I agree with you. There is a sense of movement in the “Beauty Looking Back” print. She also is positioned closer to the lower edge (or “foreground,” if we can even call it that) of the print. Perhaps this has parallels with the viewer interaction that is found in Baroque art, even if only to our Western eyes?

Hi Christina! Thanks for your comment. I agree with what you have said about the color and lines in the ukiyo-e print and French lithographs. The Japanese connection with late-19th- and early-20th-century France is a strong one, especially since Japan was opened up to Western trade and diplomacy in 1853. Ukiyo-e prints began to appear for sale in shops and art galleries in France, which led to the French obsession with Japan that was coined “japonisme” by the art critic Philippe Burty.

Sounds like an interesting paper, Heidenkind! Were you looking at 19th century or 20th century American art in your research? Perhaps those kinds of connections would help me remember more about Japanese art, too!

i can empathize with your approach to “eastern” art. Not too long ago I was in a similar situation., highly educated in my own country and illiterate in my present environment but hungry to discover Chinese art. Like you I looked at what was happening in the west at the same time. But in my case working from the Southern Song Dynasty I was taken into a period I’d largely neglected in my studies of western art history, but did recognize a development akin to the much later Romantic period in the desire to paint from within rather than simply copy.

Just thought I’d share that. I enjoy your blog, thanks.

Hi David! Thanks for sharing your thoughts! I like your observation about a desire to “paint from within,” and I’ll keep that in mind as I familiarize myself better with art form the Southern Song Dynasty. That perspective has helped me think about the poetic nature of these pieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ssong/hd_ssong.htm