Thursday, September 19th, 2013

History of the Halo in Art

Last year, in two different classes, I had students ask me about the history of the halo in art. It is an interesting topic to consider, especially since there isn’t a reference to Jesus having a halo in the Bible. I think that the closest reference to a halo in the Bible is a description of Moses being surrounded with a “crown of light” or “rays of light” (from when he came down off of Mt. Sinai, as recorded in Exodus 34:29). Interestingly, St. Jerome’s Vulgate had a translation of this verse as “horns of light,” and you sometimes see depictions of Moses with horns from the Middle Ages and onward. But that’s another story for another post, perhaps.

I thought I’d write down a bit about the early sources for the halo, in case I have more students ask the same question in the future. The halo may have come from several different sources, including classical culture. For example, the Greek god Helios is depicted with rays emanating from his head (see image above). There also are a few depictions of Apollo with halos. A Roman floor mosaic in Tunisia which has one such depiction. I’ve also heard discussions about how laurel wreaths (used to crown victors in classical societies) could be related to the halo.

In addition to classical sources, the sun disk found in Egyptian crowns may have been an early manifestation of a halo-like form. There also are similar forms related to the halo (like the nimbus or aureola) found in non-Western art, too. Some think that the halo form traveled from West to East, ending up in Ghandara and influencing depictions of the Buddha (see one example from the Tokyo National Museum from the 1st-2nd centuries CE).1

Detail of vault mosaic in the Mausoleum M (Mausoleum of the Julii), from the necropolis under St. Peter’s Basilica. Mid-3rd century CE. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Christians adopted the round halo from their contemporaries, using the circular shape to connote perfection, divinity, and holiness. I know of one early image, a ceiling mosaic from the necropolis underneath St. Peter’s (see above), which may depict Christ or Sol Invictus (the later sun god of the Roman empire). This image pre-dates the 4th century, and could be a very early example of the halo in a Christian context. After this point, halos were used for Christ and the Lamb of God, angels, the Virgin, and eventually saints.2

Some variants of the halo:

- The mandorla (an almond-shaped aureole) usually is used for depictions of Christ and the Virgin. However, the earliest representation of a mandorla appears around an Old Testament figure, specifically one of the three angels who visit Abraham (in a 5th century scene at Santa Maria Maggiore).3 The mandorla continues to become more abstract and angularly defined in later art.

- The cruciform halo is usually used for members the Trinity, especially Christ. This form of halo includes a cross within or extending beyond the circular area of the halo. An early example of the cruciform halo is found in the Miracles of the Loaves and Fishes mosaic of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna (c. 504). In Orthodox and Byzantine tradition, the cruciform also include the letters Ο ὤ Ν, which translate to mean “The Being” or “I Am,” serving as a testament to Christ’s divinity (see more information HERE).

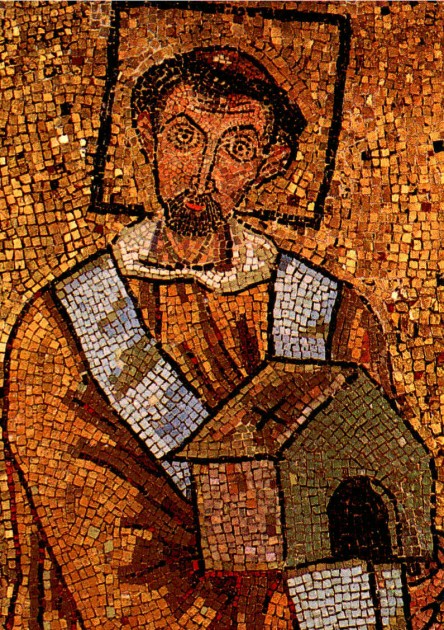

- The square halo was sometimes used to indicate that a person is still living when the work of art is created. From what I can tell, the earliest example of a square halo dates from about the early 8th century. The square, as an imperfect shape that represents the Earth, is used to draw a contrast with the perfect circle used for divine figures. (For an example, see mosaic of Pope John VII at the beginning of this post. Other examples of square halos are found at Santa Prassede in Rome, found in a mosaic of Pope Paschal I (c. 820) and a mosaic which includes a woman specified as “Theodora, Bishop”).

- The trianglular halo is sometimes used to symbolize the Trinity (example: Antoniazzo Romano, detail of God the Father, from the Altarpiece of the Confraternity of the Annunciation, c. 1489-90, Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome).

- The hexagonal halo has been used in conjunction with allegorical figures (example: Alesso di Andrea, Hope, 1347. Pistoia Cathedral, Pistoia).

- Dotted halos sometimes appear in Crusader art; they are considered one of the stylistic characteristics of this type of art (example: Saint Sergios with Female Donor icon, c. 1250s).4 The dotted halo also appears in other artistic traditions, too, including Ottonian art (example: Christ and the Apostles on the Sea of Galilee from the Hitda Codex, c. 1025-50).

- The star halo sometimes appears in depictions of the Immaculate Conception. This type of halo refers to the to the description of the Virgin being crowned with twelve stars (Revelation 12:1). Several depictions of the Immaculate Conception appear in Counter-Reformation art, including Velasquez’s The Immaculate Conception c. 1619 and Francesco Pacheco’s Immaculate Conception with Miguel Cid, c. 1621 (Seville Cathedral).

With the rise of realism in Renaissance art, the halo began to decrease (in terms of size and frequency of use). Giotto seems to have struggled with how to depict groups of figures with halos, while still giving a sense of three dimensional space, as seen in his Madonna and Child altarpiece. Masaccio tried to angle his halos to appear a little more realistic in three-dimensional space, as seen in his “Tribute Money” fresco in the Brancacci Chapel. Leonardo da Vinci only subly suggests a thin halo in many of his paintings, like Virgin of the Rocks at the National Gallery in London. In some Renaissance art, sometimes the halo was subtly incorporated into a scene, like the a firescreen (Follower of Robert Campin, Virgin and Child Before a Firescreen) or an architectural device (Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper). I like how Jan Van Eyck created thrones in the Ghent altarpiece with backs that give the suggestion of halos (see above). Beyond the Renaissance, some artists continued to suggest halos without creating a traditional halo, as seen in the drapery behind Christ in Coypel’s The Resurrection of Christ (1700).

What are your favorite depictions of halos? Why?

1 Sally Fisher, The Square Halo and Other Mysteries of Western Art: Images and the Stories that Inspired Them (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1995), 92.

2 Ibid.

3 “Mandorla,” Encyclopedia Brittanica. Available online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/361739/mandorla (accessed September 19, 2013).

4 Angeliki Lymberopoulou, “To the Holy Land and Back Again: The Art of the Crusades,” in Art and Visual Culture 1100-1600: Medieval to Renaissance, edited by Kim W. Woods (London: Tate Publishing, 2012), 134.