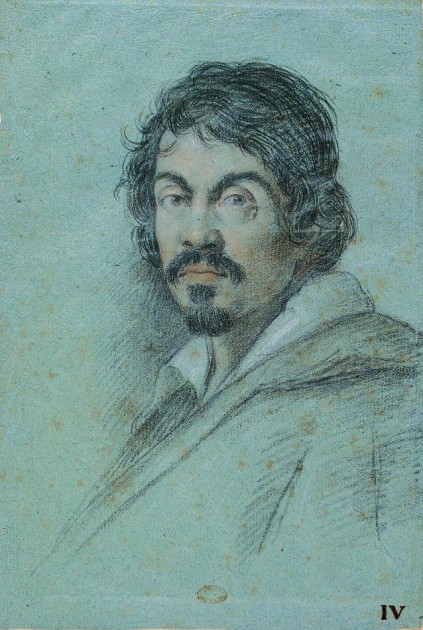

David, Death of Marat, 1793

“Murder can be an art, too.” – Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rope (1948)

________________________________________________________________

When I was a kid, I used to watch rerun episodes of “Perry Mason” on TV all the time. Maybe that series initially sparked my interest in murder mysteries. Even now, as an adult, I still like to read detective stories and watch murder mystery shows. Lately I’ve been coercing my husband to watch episodes from the fourth season of “The Mentalist” almost every night. I guess “The Mentalist” is my modern version of “Perry Mason.”

Anyhow, I thought it would be fun to write a post on art history topics that involve murder. I’m not necessarily interested in depictions of murder, though. Gruesome depictions of murder are commonplace (yawn!) in art, including David’s famous Death of Marat shown above. Instead, I thought it would be interesting to discuss when artists or art historians have been murdered, committed murder, or accused of murder. These were the three cases that came to my mind:

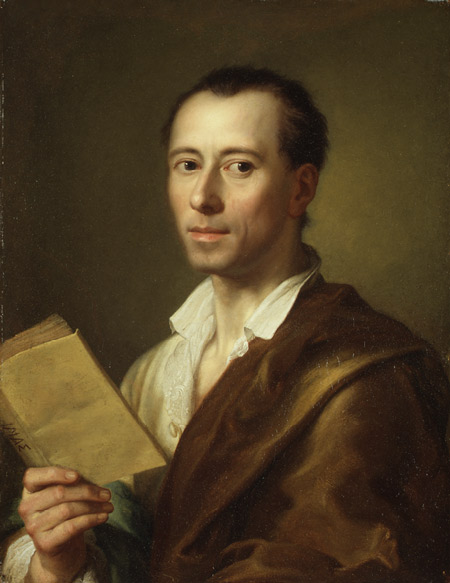

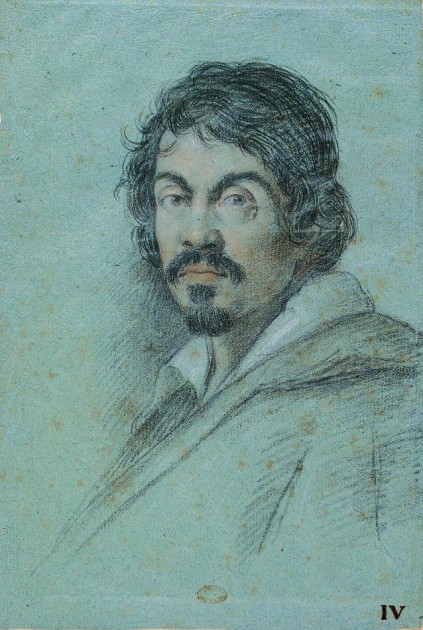

Leoni, Portrait of Caravaggio, 1621-25

1) In 1606, the volatile painter Caravaggio killed Ranuccio Tomassini. The pretext for the duel had to do with a tennis match, but art historian Andrew Graham-Dixon believes that these two men were really fighting over a prostitute. Graham-Dixon believes that Caravaggio was attempting to castrate Tomassini, since Tomassini bled to death from a femoral artery in his groin.

But Caravaggio’s associations with murder go even further. It is also thought that Caravaggio himself was murdered. While on the run from his murder conviction, Caravaggio fled to Malta and then Porto Ercole (Italy). Scholars think that Caravaggio was murdered either by relatives of Tomassoni or by the Knights of Malta (or at least one knight from Malta). The latter theory is suggested because it appears that Caravaggio was convicted of inflicting bodily harm on a noble knight in Malta. The knight (with or without his fellow knights) may have pursued Caravaggio and killed him.1

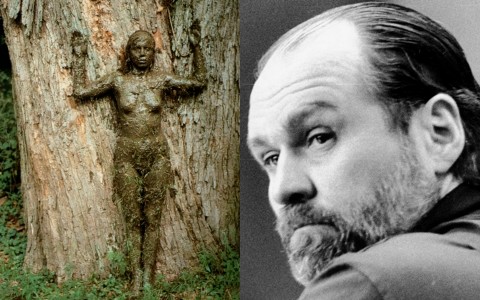

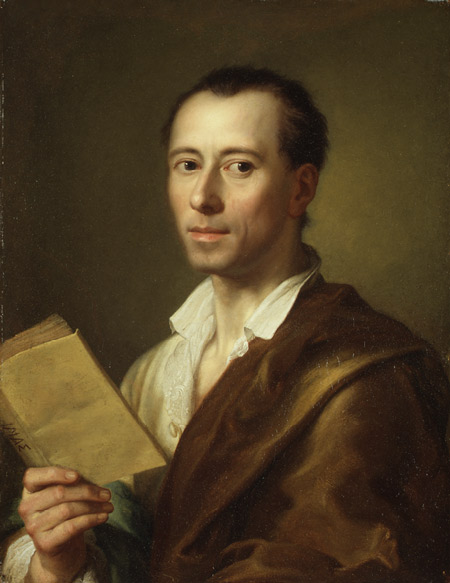

Mengs, Portrait of Winckelmann, after 1755

2) This murder story is probably one of the least expected, I think. The 18th century art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who is best known for his studies on Greek sculpture and open homosexuality, was murdered in 1768. After visiting Vienna (and being received by the Empress Maria Theresa), Winckelmann stopped at a hotel in Trieste on his way back to Rome. At that point, he was murdered at the hotel by a man named Franceso Arcangeli. Winckelmann was showing coins that had been presented to him by the Empress Maria Theresa, so it is possible that the motive for murder was monetary. However, Professor Alex Potts has mentioned other possible reasons for murder (including conspiracy or a sexual motive). Potts also explored how Winckelmann’s murder affected scholarship (both Winckelmann’s own scholarship and a later interest in the deceased art historian’s work).2

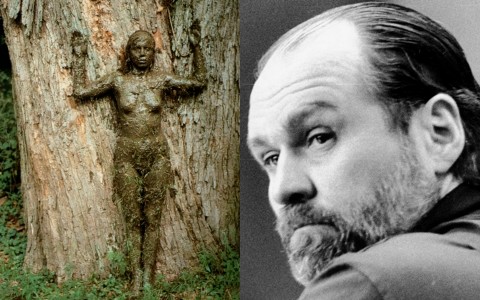

Left: Ana Mendieta, Untitled from The Tree of Life Series, 1977. Right: Photograph of Carl Andre

3) This murder story involves not one, but two, 20th century artists. In 1985 the performance artist Ana Mendieta (depicted above on the left) fell 34 stories to her death, falling from her apartment in Greenwich Village (in New York). The only other person who was with Mendieta at the time of her death was her husband of eight months: Carl Andre, the minimalist sculptor. Andre was charged with second-degree murder, but was acquitted after a three-year struggle in the court system. Art in America claims that evidence was suppressed in the trial, due to sloppy work on the part of the police and prosecutors.

The turbulent relationship between this couple has been turned into a play, “Performance Art in Front of the Audience Ought to be Entertaining.” The play is set on the night that Ana was murdered, but the curtain falls before Ana actually dies – in other words, the theatergoer is left to decide what happened right before Ana died.

Okay, now it’s your turn. Do you know of other artists or art historians who have been involved with murder cases?