Thursday, June 23rd, 2016

Barnett Newman’s Slashed Paintings

I’ve been reading this afternoon about three specific instances in which Barnett Newman paintings were slashed. The first instance of damage occurred in 1982, when a veterinary medical student attacked Barnett Newman’s painting Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue IV (1969-70, oil on canvas; 274 x 603 cm). The painting, which was on display at the Nationalgalerie Museum in Berlin, offended and frightened the student, who claimed that the painting was a “perversion of the German flag.”

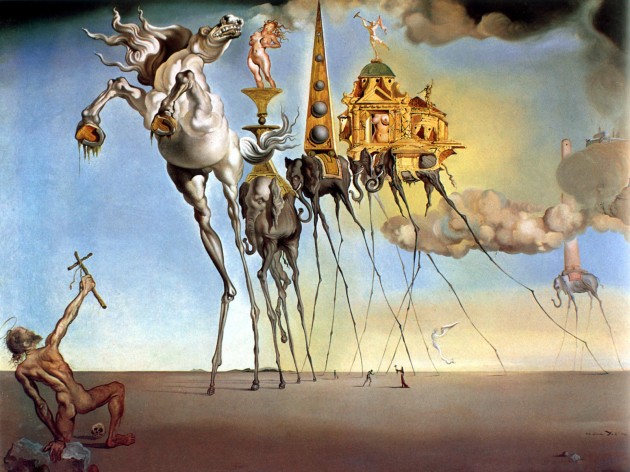

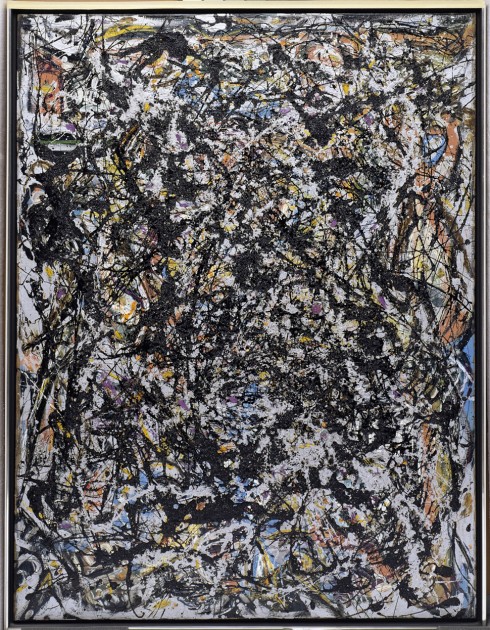

The second and third incidents in which a Newman painting was damaged were performed by the same person, at the same museum! In March of 1986, Gerard Jan Van Bladeren walked into the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and used a box cutter to slash eight incisions into Newman’s painting Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III (shown above). Van Bladeren, a mentally-disturbed realist painter who rejected modern art (and wanted to make Newman’s painting serve as an example of his rejection), was arrested and served five months in jail.

However, Van Bladeren should have been watched more carefully: over ten years later, in 1997, he walked into the Stedelijk Museum again. Upset over the restoration of Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III, Van Bladeren decided to attack another painting by Newman, Cathedra (shown below). Van Bladeren used a small Stanley-brand knife to slash this painting seven times. Afterward, Van Bladeren calmly leaned against a wall and waited for the police to arrive!

Such marks on Newman’s monochromatic surfaces are hard to hide, and pose a problem for conservators. In fact, when Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III was not put public display until 2001, it was met a lot of criticism. The Stedelijk Museum was upset with the restoration of Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III, and some said that the painting lost its appeal due to the mishandling and misapplication of paint. When the Stedelijk Museum opened in a new location, the Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III was put on display in the new building in 2014. The museum celebrated (and also justified) the return of this restored painting with this video:

The Stedelijk Museum decided to use their own in-house conservators to restore Cathedra, which arguably would have been an even more difficult project because of the varied layers of paint. This variation contributes to the ethereal nature of the painting, since the painting seems tangible and intangible at the same time. It seems like the museum is happy with their conservation efforts for Cathedra, since the painting is highlighted in the video above (and in fact, seems to get even more praise for its visual properties than Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III).

I think something very bold, powerful, and even ineffable is expressed by paintings by Newman, especially because they often appear on a large scale. The paintings overwhelm and fill the visual field of the viewer, and perhaps these factors contributed to how these vandals felt unsettled (and subsequently reacted to) Newman’s works of art. (It is interesting to me that the two Stedelijk paintings are the same size!) Perhaps Barnett Newman might even have been able to understand these attacks, since he wrote in 1943, “The painter is concerned . . . with the presentation into the world mystery. His imagination is therefore attempting to dig into metaphysical secrets. To that extent, his art is concerned with the sublime. It is a religious art which through symbols will catch the basic truth of life.” Perhaps these sublime “metaphysical secrets” are too unsettling for some people to have revealed, and they react in a violent way?