Friday, February 20th, 2015

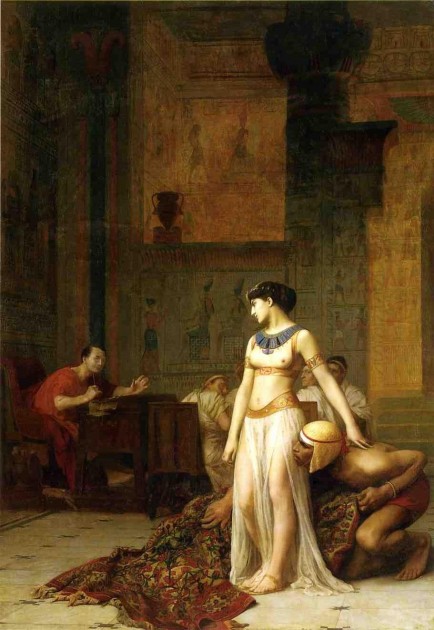

Cleopatra and the Carpet Myth

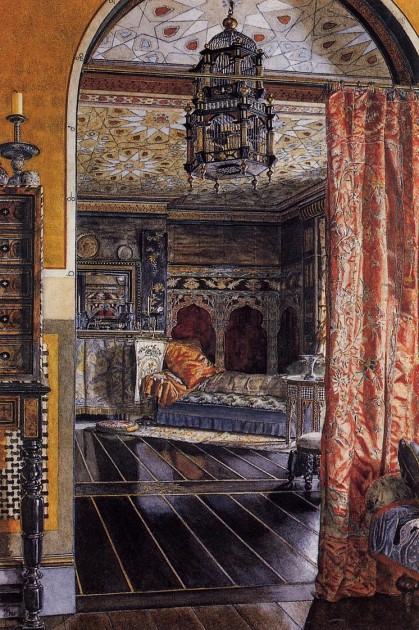

Today in class I showed my students the beginning of a short video clip by Sotheby’s about Gérôme’s Cleopatra and Caesar (shown above). The clip highlights how Cleopatra is depicted as having hidden in a rug (either a Persian or Turkish rug), which isn’t an accurate representation of what is described in Plutarch’s text. However, given the taste for exoticism in Orientalist art at the time, I can see why Gérôme’s opted to depict a carpet rug instead, despite the cultural inaccuracy and anachronism.

The video clip mentions how Gérôme’s painting has influence on Cecil B. DeMille, who directed Cleopatra (1937, starring Claudette Colbert). I can see how the inaccurate inclusion of a carpet could perhaps connect to this point, since a carpet rug was used to smuggle Cleopatra into Caesar’s presence in DeMille’s film (see image below). Similarly, a later version of Cleopatra which was directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz (1963, starring Elizabeth Taylor) has a great scene which shows the queen dramatically and unceremoniously unrolled from a rug before Caesar (who is played by Rex Harrison). I can see why these filmmakers opted to depict a lavish carpet – it is more visually striking and dramatic than a sack used to hold bedclothes (as described by Plutarch).

To be fair, though, I want to highlight something about this “carpet myth.” While I think that Gérôme’s painting may have inspired 20th century filmmakers to portray Cleopatra with a carpet, other sources should be acknowledged too. I don’t think that this painting, which was completed in 1866, should be highlighted as the ultimate source for the myth. In fact, a 1770 translation of Plutarch by Langhorne introduced the word “carpet” instead of “sack of bedclothes.”1 A few decades after Gérôme’s painting was completed, George Bernard Shaw highlighted the carpet in his 1898 novel, Cleopatra and Caesar, by writing, “It is a Persian carpet – a beauty!”2

Do you know of other examples in art or popular culture that display Cleopatra with a carpet?

1 Christopher Pelling, Plutarch Caesar: Translated with an Introduction and Commentary (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 385.

2 Ibid.