Cover image of "Irene Parenti Duclos: A Work Restored, an Artist Revealed"

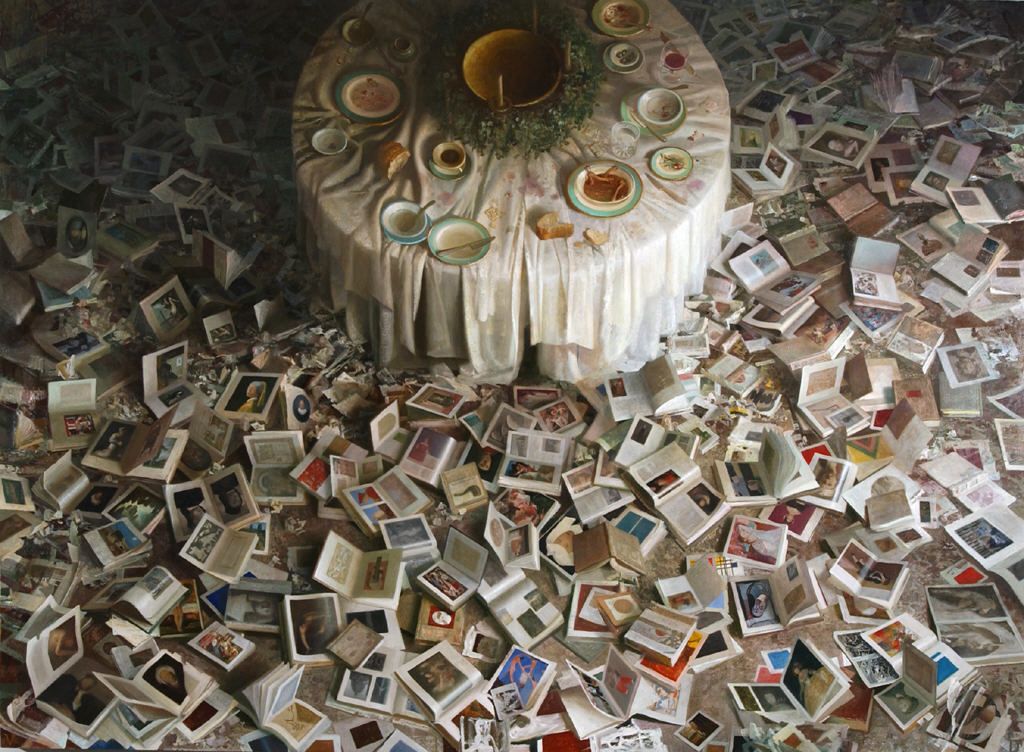

Over the past few weeks I have had the pleasure to read a new book on a female painter, Irene Parenti Duclos. This book, Irene Parenti Duclos: A Work Restored, an Artist Revealed, was published by the Florentine Press in October 2011. I wasn’t familiar with Duclos before reading this book; she was well-respected female painter in 18th century from Florence. This book was written (in part) to discuss the restoration of Duclos’ copy of Andrea del Sarto’s Madonna del Sacco (18th century, detail of Duclos’ copy appears on book cover above). Coincidentally, the restoration of the Duclos canvas occurred at the same time that Andrea del Sarto’s original fresco (1525) underwent restoration (compare del Sarto’s pre-restoration fresco to the restored version). Scholars were able to collaborate and learn more about Duclos (and the del Sarto fresco) during this restorative period. You can read a little more about the Duclos copy and restoration here.

Duclos' "Madonna del Sacco" (18th century) in the Accademia post-restoration

This book is great for a lot of different reasons. For one thing, I like that this book was written and promoted with the help of the Advancing Women Artists Foundation. (What a great cause!) I also like the book has appeal to a lot of different types of people: art historians, feminists, connoisseurs, and restorers. The book pages are divided to accommodate text in two languages (English and Italian), and therefore appeals to an international audience.

Book chapters are divided into different topics of interest. Some of the chapters are more technical than others (especially the last two chapters, which discuss the restoration of the canvas and the digital microscopy used in the process). Although these last two chapters were the most difficult for me to read (my art-historical brain isn’t used to scientific language!), I still thought the discussion was interesting.

As a feminist art historian, I was particularly interested the discussions on female artists. I liked reading a little bit more about Angelica Kauffman, Elizabeth Vigeé Le Brun, and other Italian female artists with whom I was not familiar before. Although Duclos was a painter in the 18th century, the discussion of female artists even expands to include the Renaissance artist, Suor Plautilla Nelli. I was happy to see that Nelli was discussed in detail; I learned just a little about her when I read Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, but I’ve had difficulty learning more biographical information about her. I also appreciated that this book served as a call to action. Nelli’s large-scale painting from the 16th century, Last Supper (which is the only known version of this subject matter produced by a female artist) is in dire need of restoration. Hopefully this publication will bring more exposure to the works of female artists that need preservation and attention.

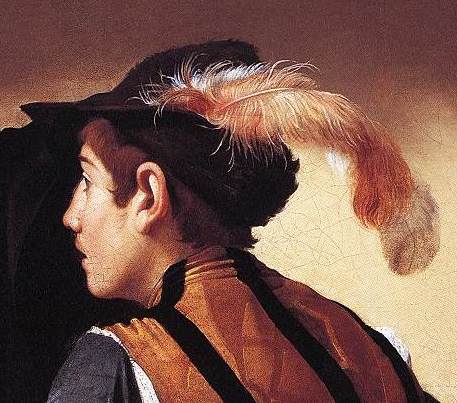

Johann Zoffany, detail of "The Tribuna of the Uffizi," 1772-78

I also enjoyed reading the chapter on the fondness for copying art during the 18th century. Today I think that artistic copies often are viewed with some disdain, implying that the copy is of lesser quality than the original work of art. In the 18th century, however, copies were seen in a much more favorable light. The collecting of copies was seen as a mark of respectability and prestige. One of the paintings which typifies the 18th century rage for Italian works (and the copying of such paintings) is Zoffany’s The Tribuna of the Uffizi (1772-78). Not only did Zoffany copy many great works of art to produce his final canvas, but he also includes an artist in the process of copying a work of art (see above)!

Along the lines of copying and prestige, though, I found it interesting that the book emphasized that 18th century female artists received acclaim as copyists and portrait artists.1 While I do think that this is true, I think it is also important to emphasize that women were still not considered capable of the highest level of achievement (i.e. history painting) as their male artistic counterparts. It seems to me that women only were acclaimed for the types of art which men found them capable of producing. A woman might be able to impressively copy or paint what she saw in front of her (as is the case with portraiture), but it seems apparent that women were also thought (by men) to lack the imagination and intellect necessary to create large-scale history paintings.

But enough of my little rant. This book is very interesting and an informative read. I highly recommend it. And now for the big news: a GIVEAWAY! I am able to offer a copy of this book free, thanks to the generosity of the Florentine Press. Local and international readers may enter this giveaway. I will be randomly selecting one winner (using this site) on December 31, 2011. So you have ten days to enter this giveaway! You can enter your name up to four times. Here are the ways you can enter:

1) Leave a comment on this post!

2) Tweet about the giveaway (be sure to include my Twitter name: @albertis_window in your tweet, so I can find it). After tweeting, leave a comment on this post to let me know too, please.

3) Write about this giveaway on your own blog, and then include the URL in a comment on this post.

4) Become a fan of The Florentine on Facebook and enter your email address here (so we can cross-check it with your other entries) in the giveaway for a book by Linda Falcone – this way you have a chance to win yet another book! Please also leave a comment on this post, to let me know that you became a fan on Facebook.

While you wait to find out if you won a free copy of the book, check out this nice video of the book presentation.