Saturday, February 28th, 2009

Leonardo’s Sketches and Writing

Since Leonardo da Vinci was a perfectionist, he manages to complete only a few paintings during his career. In contrast, there are many drawings and sketches from Leonardo’s notebook that exist today. These sketches and studies of human anatomy are proof that the artist was a “Renaissance man” – not only was he interested in the arts, but he was also studied anatomy and physiognomy (among other scientific things). In truth, Leonardo felt that the scientific study of anatomy and nature was related to art. Leonardo held the “conviction that the artist must understand the deepest causes of motion and emotion if he is to create figures that can function adequately as imitations of nature.”1

Since Leonardo da Vinci was a perfectionist, he manages to complete only a few paintings during his career. In contrast, there are many drawings and sketches from Leonardo’s notebook that exist today. These sketches and studies of human anatomy are proof that the artist was a “Renaissance man” – not only was he interested in the arts, but he was also studied anatomy and physiognomy (among other scientific things). In truth, Leonardo felt that the scientific study of anatomy and nature was related to art. Leonardo held the “conviction that the artist must understand the deepest causes of motion and emotion if he is to create figures that can function adequately as imitations of nature.”1

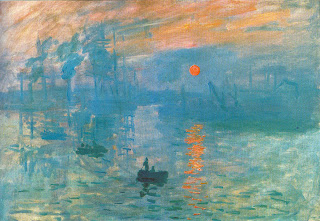

Drawings such as The Fetus and Lining of the Uterus (c. 1511-1513, shown above) are important today because they established a precendent for scientific illustration, particularly with Leonardo’s use of cutaway views.

However, the thing I find fascinating about Leonardo’s notebook is actually not the sketches themselves, but the combination of his sketches and writing. Da Vinci usually made backwards annotations in his notebook. Art historian Michael Ann Holly suggested that Leonardo’s writing allows for an interesting interplay between the words and the text. Since the Western eye moves from left to right (particularly while reading, but Holly also suggests that this can happen while looking at images), then the eye will move back across the notebook page (from right to left) when proceeding from the image to Leonardo’s handwriting. Therefore, Holly suggests that the eye to moves back and forth across the page because “Leonardo’s words and images scroll together in a vortex of unfolding mobility.”2 She also finds that since Leonardo is writing backwards, there is no competition between words and images. Words “unwrap unto pictures, only to be metamorphosed back again at the other end of the line.”3

I think this is such an interesting interpretation of Leonardo’s backwards writing. As far as I know, this is the only article that offers an art historical interpretation of these strange annotations. Does anyone know of any other articles?

What do you think of Leonardo’s sketches and backwards writing? Do you like Holly’s interpretation?

1 . “Leonardo da Vinci.” In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.erl.lib.byu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T050401, accessed February 28, 2009).

2 Michael Ann Holly, “Writing Leonardo Backwards,” New Literary History 23, no. 1 (Winter, 1992): 175. It should be noted that this article actually is not about Leonardo; Holly uses Leonardo as an allegory for discussing historical consciousness in the late 20th century.

3 Ibid.