Tuesday, February 10th, 2015

The World Fair and Datsolalee’s Baskets

It’s always interesting to me when art historical worlds collide. Just yesterday I was writing about how Anna Alma-Tadema, the daughter of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, exhibited the watercolor The Drawing Room at the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chacago. And then today, in a tour of an exhibition of American Indian art curated by David W. Penney, I learned that the Washoe basketweaver Louisa Keyser (called “Datsolalee”) exhibited her basketwork at this same exhibition! In fact, Penney said that this exhibition helped Datsolalee to achieve more fame and renown for her basketweaving.1

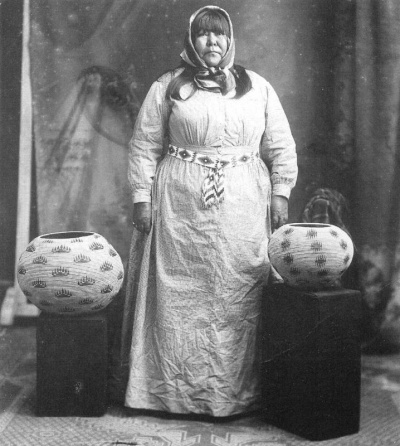

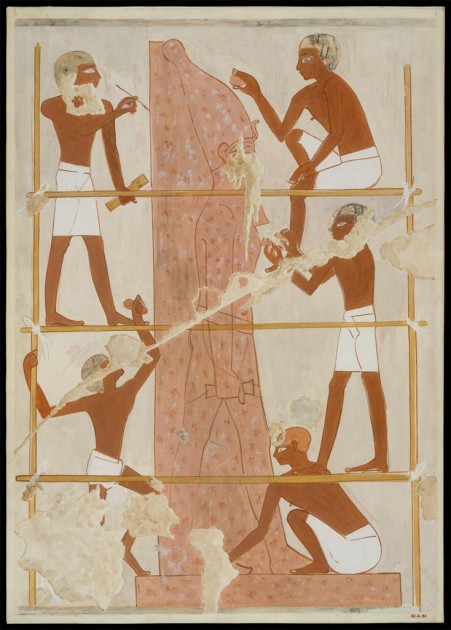

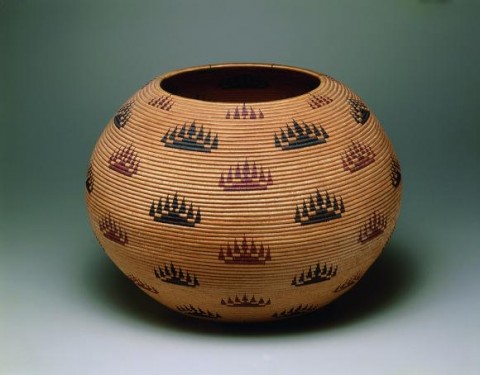

Louisa Keyser (Datsolalee), Degikups (“day-gee-coops”) basket bowl (“Harbor Lights” design, as dubbed by Keyser’s dealer), 1907. Willow shoots, redbud shoots, bracken fern root.

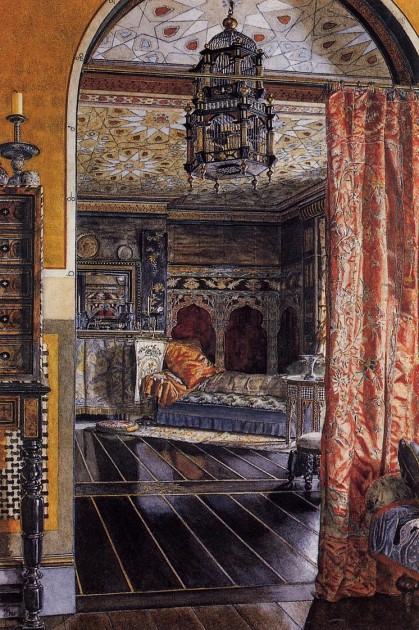

It’s striking to me how a Western taste for “the exotic” can be found in just these two examples that I have been thinking about this week, although the “exotic” looks to two different non-Western cultures. Anna Alma-Tadema’s watercolor contains textiles, tilework, and laquered furniture which are Eastern and/or Eastern-inspired in style. The inclusion of Datsolalee’s baskets in the 1893 fair is one way that Westerners were interested in American Indian cultures. This fair also was the first to include a live exhibition of American Indians (see one photo HERE).2

It seems to me that such live exhibitions and displays could help to disseminate an understanding of American Indian culture on some basic level, but the sheer spectacle and to-be-looked-at-ness of these displays suggest an “exoticization” and Other-ing on part of the Westerners to who organized and attended the fair. Although I realize that this Western interest in (and exploitation of!) the exotic can be found at many other of the World Fairs that were held during the 19th century and beyond, I think that this particular fair is somewhat-wryly appropriate, since the Columbian Exposition celebrated the 400th year that Christopher Columbus arrived in the New World in 1492. Given this context, it seems fitting that Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show performed at the exposition, just outside the main entrance to the fair!3

Datsolalee is an interesting artist to me, especially since she was able to be successful, due to and in spite of the Western culture which encroached and superimposed itself on her people. Datsolalee’s people, the Washoe, are from the area in the United States called northwest Nevada. She married a man of mixed blood, Charlie Keyser, and made her living as a camp cook and laundress, but her skills at basketweaving were soon recognized by Amy and Abram Cohn. The Cohns became Datsolalee’s art dealers (in fact, they gave her the “Datsolalee” nickname, perhaps as a marketing strategy) and promoted her work.4 She wove baskets for Cohn’s Emporium for thirty years until her death. (Read more details of her biography HERE and an article written in the Reno Evening Gazette just after her death in 1925.)

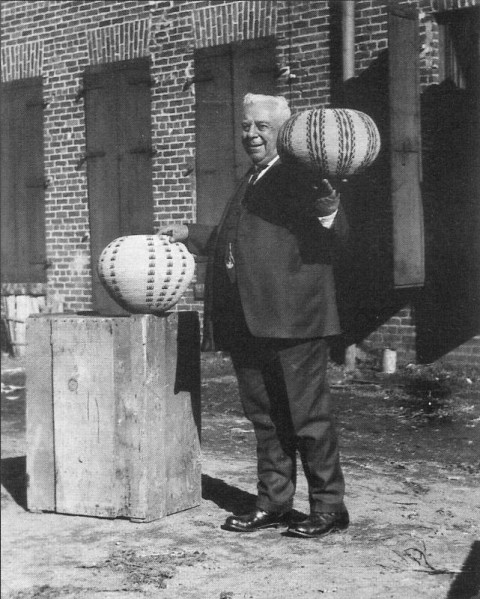

One of the reasons why Datsolalee is well-known today is not just because she achieved exposure through Cohn’s Emporium or the Columbian Exposition, nor just because of her impressive craftsmanship (her best work is recorded to be baskets that had eighty strands to an inch!), but because of the cataloging of her baskets that was done by her dealer, as well as the bill of sale that was given with her baskets. The Cohns wrote these bills of sale to include several detailed bits of information: a description of the basket, stitches to the inch, the design of the basket, the amount of time it took to create the basket, and Datsolalee’s handprint. Datsolalee used her handprint, which was copyrighted, as a signature! As a result, these baskets were easily identified and connected back to her, which wasn’t always the case with American Indian weavers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although the Cohns were known to fabricate and exaggerate elements of Datsolalee’s biography, as well as include incorrect information on the bills of sale, these bills still helped to connect the baskets to Datsolalee as a specific, unique individual.5

On one hand, the “exoticizing” of American Indian culture and craft at Western venues like the 1893 Columbian Exposition likely spread some inaccurate information or perceptions of American Indians to those who visited the fair. At the same time, though, this Western venue helped to promote Datsolalee and her basketweaving. And, thanks to the the detailed bills of sale written by Datsolalee’s art dealer, we know about Datsolalee today (although, admittedly one needs to separate the truth from myth). I think these points help illustrate that the dissemination and preservation of knowledge, especially accurate knowledge, is a tricky thing when it comes to cross-cultural interactions.

What do you know of other ways in which Westerners helped to preserve the information about American Indian craftsmen and artists? Do you know anything else about Datsolalee which interests you? I learned today that she requested to be buried with one of the last baskets she made, which I thought was fitting.

1 Tour with David W. Penney, Seattle Art Museum, February 10, 2015.

2 Elizabeth Hutchinson, The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art, 1890–1915 (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2009), p. 43. Available online HERE.

3 Marsha C. Bol, “Defining Lakota Tourist Art,” in Unpacking Culture: Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, by Ruth B. Phillips, Christopher B. Steiner, eds. (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 1999), p. 200. Available online HERE.

4 The name “Dat-so-la-lee” means “Big Hips” in Washoe. However, I also found elsewhere that the nickname was actually due to “Dr. S.L. Lee,” the first white man to admire and take an interest in Datsolalee’s baskets. See HERE.

5 For more information on the myths that were propagated by the Cohns, see Christopher Ross, “Datsolalee and the Myth Weavers” in The Historical Nevada Magazine: Outstanding Historical Features from the Pages of Nevada Magazine by Richard Moreno, ed. (Reno, Nevada; University of Nevada Press, 1999), 86-94. Available online HERE.