Saturday, April 11th, 2015

Tapestries and Social Metaphors

About two weeks ago, I had the opportunity to hear the contemporary artist Ann Hamilton give a public lecture. This lecture was absolutely fantastic, and I have been thinking about it ever since. Hamilton’s work is very compelling to me, since her installations and pieces often incorporate textiles or fabrics. These textiles and fabrics, which are comprised of single threads woven or knit together, serve as a beautiful social metaphor for Hamilton (as a combination of the singular “I” and plural “we”). Since listening to this lecture, I’ve been thinking of several ways that tapestries (and even the interconnectedness of the Internet as a “web”) can relate to this social metaphor.

The interconnectedness of individuals is especially apparent to me in Ann Hamilton’s installation “the event of a thread” (Park Armory, New York, 5 December 2012 – 6 January 2013). While there are several components to this installation, I’m particularly drawn to the immense white fabric and swings which were set up in part of the space. The fabric inherently serves as a reference to Hamilton’s social metaphor, because it is a textile, but this idea of the interconnectedness of people especially was emphasized through the swings that are attached to the fabric. Each swing was connected to another swing through a system of pulleys. As people swung back and forth, the white tapestry rose and fell to match the rhythm of their movements. As a result, the tapestry served more of a visual image of the connectedness of people rather than of any sort of barrier between them. You can see some videos of this installation HERE and HERE.

I love the idea of a tapestry as something which expresses the connection between people. Since this lecture by Ann Hamilton, I’ve been thinking about ways that other tapestries give visual evidence of social collaboration and interconnectedness. One example which has stuck out to me is the series of tapestries that Raphael designed for the Sistine Chapel. These ten tapestries serve as a unique example of social and geographic connectedness: they were designed as cartoons by Raphael in Italy between 1515-1516, but were woven in Brussels in the workshop of Peter van Aelst between 1516 and 1521. Given that some areas of Europe were disrupted by the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation at this time, I think that these tapestries also serve as a unique metaphor of Catholic solidarity between Belgium (which was part of the Seventeen Provinces of the Low Countries at this time) and the Vatican.

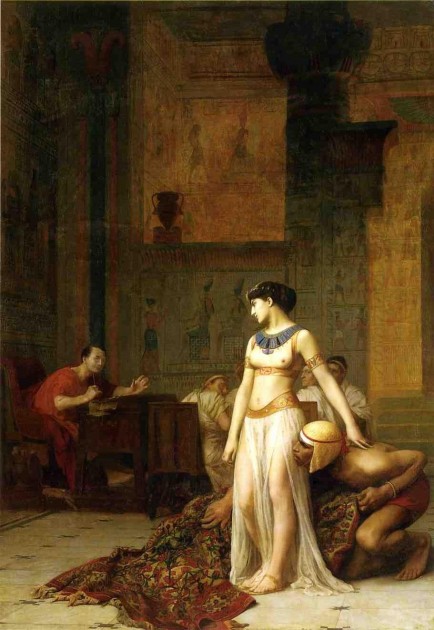

Raphael and Pieter van Alest, “The Miraculous Draught of Fishes,” from the Raphael Tapestry series, c. 1519. Tapestry in silk and wool, with silver-gilt threads, height 490 cm, width 441 cm. Musei Vaticani, Vatican. Image courtesy the Web Gallery of Art

Beyond the woven medium itself, these tapestries also suggest a longing for people to interconnect themselves with the biblical and classical past. I’m particularly intrigued by The Miraculous Draught of Fishes tapestry (shown above), which is decorated with a border that recalls the appearance of relief carvings on classical sarcophagi, but depicts two episodes from the life of Pope Leo X. Additionally, the main scene depicts a biblical event, but includes references contemporary to the Renaissance period. In the back left corner of the tapestry, for example, there is a depiction of Vatican hill with the towers along the wall of Leo XI. Saint Peter’s also is depicted as under construction (a very anachronistic inclusion when one considers how Simon Peter is only just being called as a “fisher of men” in the foreground!).

Raphael and Pieter van Alest, detail of Vatican hill within “The Miraculous Draught of Fishes,” from the Raphael Tapestry series, c. 1519.

So, the creation and appearance of the Raphael tapestries can relate to the interconnectedness of people, either across geographic boundaries or historical divides. From a reverse perspective, we can also see that the displacement of these tapestries serve as evidence of social rifts. During the Sack of Rome in 1527, troops of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V looted and pillaged the city, and thousands upon thousands of people were murdered. These tapestries tie into this event, since they were stolen and not returned until the 1550s (although only seven tapestries made their way back). The remaining tapestries were stolen again when French troops entered Rome at the end of the 18th century. It is interesting to me how one of these tapestries was reportedly burned in order for people to try and gain access to the precious material of the silver-gilt threads.1 Therefore, the material which once helped to bind this tapestry together was intentionally destroyed when people metaphorically pulled apart from each other.

All of these thoughts about tapestries and social metaphors have caused me to think also about the Internet as a tapestry which binds people together. My friend, the late Hasan Niyazi, was the best “weaver” of people via the Internet that I have met thus far. As an art history blogger with a particular passion for Raphael, Hasan sought to not only share his research and ideas regarding art, but also to connect the online art historical community together. His untimely death has caused an absence which is still keenly felt among art history bloggers. I think that we are still seeking for ways to make sure that we keep Hasan’s tapestry together. This post about social metaphors and Raphael’s tapestries is dedicated to Hasan’s memory, especially in light of Raphael’s birthday earlier this week (April 6th).

1 There are several different accounts that report when some of these missing tapestries could have been burned. Passavant suggests that one specific tapestry was burned in near the end of the 18th century (incorrectly written in the text as 1789 instead of the 1798 French invasion of Rome). See Johann David Passavant, “Raphael of Urbino and His Father Giovanni Santi,” p. 298, available online HERE).