Tuesday, July 10th, 2018

Book Review: “The Museum of Lost Art”

I recently finished reading Noah Charney’s new book The Museum of Lost Art. I have an academic crush on Charney’s work – he always manages to write about fascinating topics that I wish I had thought to write about myself. I’m glad that he is one step ahead of me, though, because he writes in a very engaging and approachable way. I wish that more art history texts were written like his.

The book is divided into sections, and within each section Charney considers different ways for how a work of art can be “lost.” For example, some works of art are destroyed intentionally or destroyed accidentally, while others are altered from their original conception. Each section is tied unified by beginning and ending with an anecdote that relates to the topic. I found this to be a bit confusing when I read the first section, but then I perceived what Charney was doing and the remaining sections made more sense.

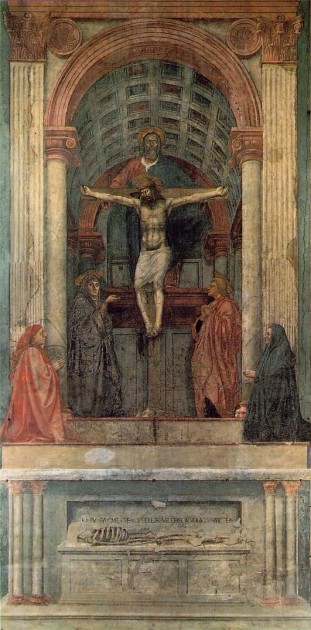

The thing that I liked most about The Museum of Lost Art was that I learned new things about famous works of art that I thought I already knew well. For example, I didn’t know that Masaccio’s Holy Trinity painting was covered up with a false wall in the latter part of the 16th century when Vasari was hired to alter the space.1 This canonical painting, which appears in most introductory art history textbooks as an example of mathematical (linear) perspective, was only rediscovered in 1860 when the church was remodeled.2

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533. Oil on panel, 207 x 209.5 cm (81.5 x 82.5 in), National Gallery, London

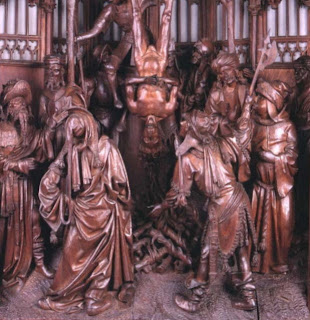

I also was also intrigued to learn that part of Holbein’s painting The Ambassadors was “lost” at some point after it first was painted in 1533. The crucifix in the upper left corner originally was created to be partially obscured by the green curtain (which has been connected to the political tension of the day), but at one point the crucifix was completely painted out. Only in recent times, when conservators at the National Gallery cleaned this painting in 1891, was the crucifix discovered.3 This clear alteration before 1891 suggests that this political message (which references Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church through the formation of the Church of England) was offensive or problematic.

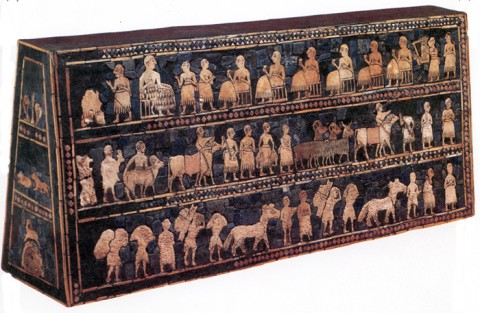

The only section that I wish had a little more attention in this book is that of the “Looting in the Ancient World.” I think that the ancient Near East could have gotten more coverage here in the book, since many works of art were altered or lost due to the different warring groups who lived in this area. Probably my favorite article which discusses this topic is Marian Feldman’s “Knowledge as Cultural Biography: Lives of the Mesopotamian Monuments,” which includes a discussion of the Akkadian King portrait head. I realize that Charney was giving a brief overview of this topic in his book, but I do wish that the ancient Near East could have received a bit more discussion.

Otherwise, I really did enjoy this book and I heartily recommend it to anyone who is interested in the biographies of works of art, art crime, looting, conservation, and restoration.

1 Noah Charney, The Museum of Lost Art (Phaidon: New York, 2018), 215.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid., 235.