Thursday, March 26th, 2009

Nefertiti and CT

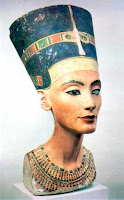

I never thought I would be interested in reading an article in my father-in-law’s Radiology magazine. However, I was intrigued that the cover of their recent issue has a picture of the famous Nefertiti statue bust (made by the artist Thutmose, Dynasty XVIII (ca. 1353-1335 BC)). Recently, some computed tomography (CT) performed on the core and surface of the statue bust has revealed new information.

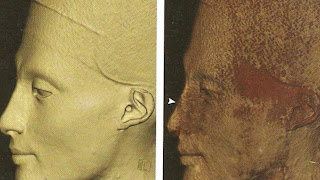

According to this article, there are slightly different physical characteristics which appear on the inner core of the statue (consequently revealing a “second hidden face”).1 On the inner core, the CT revealed that there “creases around the corners of the mouth and cheeks, a less harmonious nose ridge, and less prominent cheekbones. The nose [also] showed a slight bump.”2

The visible outer layer (left) and the inner layer (right) show a difference in the nose (the bump is indicated by an arrow)

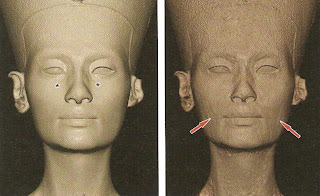

Although the outer surface of stucco refined and softened these wrinkles and bumps, it is also interesting that there is a more pronounced shaping of the eyelid corners on the outer layer (see image below). This emphasis on the outer eyes supports interpretations that this bust was supposed to be recognized as a depiction of a mature woman, not of a woman of flawless beauty.”4

The shaping of the eyelid corners on the outer (visible) surface can be seen on the right (indicated by *). On the inner core (left) creases in the corners of the mouth (arrows) were found.

The shaping of the eyelid corners on the outer (visible) surface can be seen on the right (indicated by *). On the inner core (left) creases in the corners of the mouth (arrows) were found.I think it’s fascinating to look at different facial characteristics on the inner core – perhaps the inner core is a more correct representation of how Nefertiti appeared in life. It’s great that technology can help historians and archaeologists learn more about art. In this study, CT also showed more information regarding the types of tools and materials that were used to sculpt the bust. In addition, further details were revealed about the thickness of the stucco, which will serve as useful information for conservators.

Although I didn’t understand all of the scientific terminology or system of measurement used in this article, it was still interesting to read. Perhaps I should pick up Radiology more often?

1 Alexander Huppertz et al, “Nondestructive Insights into Composition of the Sculpture of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti with CT,” Radiology 251, no. 1 (April 2009): 236.

2 Ibid. On a side note, I think that this slight bump makes Barbra Streisand’s tribute to Nefertiti seem especially appropriate! This photograph of Streisand was taken in conjunction with a 1966 episode of “Color Me Barbra,” in which Streisand performs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art next to the bust of Nefertiti.

3 Ibid., 239.

4 Ibid.