Friday, January 30th, 2015

Winking in Art

This afternoon my students and I were discussing some of the proverbs that are referenced in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s complex painting Netherlandish Proverbs (1559). One student pointed out one particular detail on the wall of the house that I had never noticed before: a pair of open scissors with an eye placed above. I wasn’t familiar with a proverb or a reference to this detail in the painting, so I looked it up afterward.

It turns out that these two symbols are a reference to winking! This image is a play off of the words “Een knip oog,” which means “snip-eye,” or a wink.1 Scholar Alan Dundes, who wrote about the appearance of this symbol in Pieter Bruegel the Younger’s copy of his father’s painting, explained that through this symbol “Bruegel the artist is winking at his audience and he expects the viewer to understand that what he has painted in a huge put-on.”2

Learning about this fun detail made me wonder about the history of winking and whether other winks (either literal or symbolic) appear in art. I haven’t been able to find any scholarly information on the cultural history of winking (if anyone does find something, please let me know!), but I have noticed that obvious references to or depictions of winking appear in examples of art from the Renaissance and onward. (I also realized that it is futile to determine if ancient figures in the composite pose are winking: if the head is in profile view, then only one eye is visible to the viewer, which makes it impossible to ascertain whether a second eye would be open or closed! Ha! I like the thought that Egyptians are actually winking in all of their art, but we just can’t tell.)

I was also interested to see that references to winking appear in both Western and non-Western art. Here are a few examples I came across:

Giuseppe Maria Crespi, “The Courted Singer,” 1700s. Oil on canvas, 58 x 46 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Image courtesy the Web Gallery of Art.

In this painting by Crespi, The Courted Singer (shown above), the winking figure of on the left reminds the viewer that the scene, which depicts a singer being courted, is not inherently gallant or noble. Instead, this singer and her affections are essentially being “bought” with the jewelry and riches offered to her.

Simon Vouet, “The Fortune Teller,” c. 1618. Oil on canvas, 120 x 170 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Image courtesy the Web Gallery of Art.

Winking was also used between characters within works of art, so that the viewer could understand when a figure was sly or involved in trickery. In this painting by Vouet, a man on the right of the canvas steals the purse from a gypsy woman (who is reading the palm of the woman on the far left). This thief winks to a male accomplice, who looks to me like he might be winking in return.

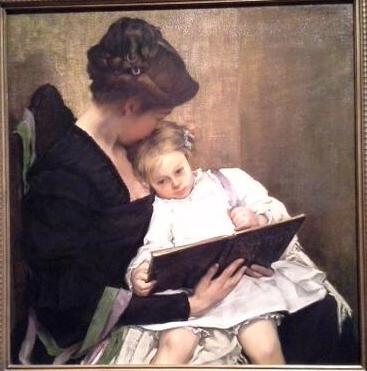

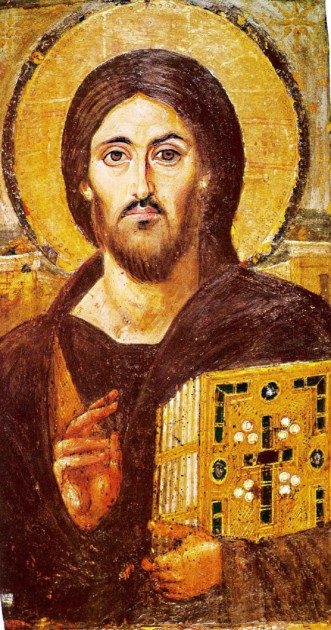

Master of the Winking Eyes, “Madonna and Child,” ca. 1450. National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington DC.

Although the winking in this picture may be an aesthetic effect rather than an actual part of the subject matter, I still wanted to include this painting by the so-called “Master of the Winking Eyes.” This piece is included in a current exhibition dedicated to representations of the Virgin Mary in art, which includes a section on representations of her as a wife and mother. This painting, among another in the show, prompted one writer to publish this article: “Did the Virgin Mary Tickle the Baby Jesus?”

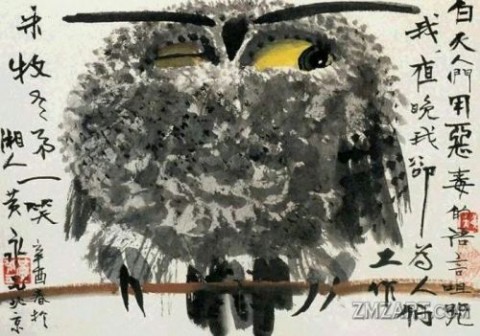

Huang Yongu’s Owl is an interesting depiction which caused a lot of controversy. Some interpreted Yongyu’s painting as a self-portrait of the artist who expressing a critique of socialism, and the painting was officially condemned as blasphemous by the Ministry of Culture in March 1974.3 The winking eye in this instance was thought by some to imply, on a basic level, a critique of the socialist system (e.g. officials were turning a blind eye to incorrect behavior). Others did not agree with this interpretation. Even Chairman Mao, who was frustrated with the extent of censorship happening at the time, said with exasperation, “An owl habitually keeps one eye open and one eye closed. The artist does possess the common knowledge, doesn’t he?”4 Yongu created other versions of the winking owl after this 1973 fiasco, such as this 1977 version and 1978 version.

Of course, to end this list, I have to include a .gif of the Nefertiti bust winking. (Since she has an unfinished eye, she does look a little like she could be winking today.) Do you know of other representations of winking in art? I’m sure there are lots of .gifs with winking works of art too, and feel free to also share those in the comments below!

1 Eric Nicholson, “Et in Arcadia the Dirty Brides,” in Transnational Mobilities in Early Modern Theater, by Professor Robert Henke and Dr. Eric Nicolson, eds (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2014, p. 99.

2 Alan Dundes, “‘How Far Does the Apple Fall from the Tree?’: Pieter Bruegel the Younger’s Netherlandish Proverbs” in The Netherlandish Proverbs: An International Symposium on the Pieter Brueg(h)els, ed., Wolfgang Mieder (Burlington: University of Vermont Press, 2004): 20. Citation also found online HERE.

3 The painting was subsequently put on display in a Black Paintings Exhibition, in order for its subversive content to be publicly shamed. Eugene W. Wang, “The Winking Owl: Visual Effect and Its Art Historical Thick Description,” in Critical Inquiry 26, no. 3 (Spring 2000): 435. Article available online HERE.

4 Ibid., 436.