Wednesday, November 5th, 2014

Frank Capra, Gauguin, and Diagonal Lines

Lately, in coordination with my volunteer responsibilities at a local art museum, I have been reading What Are You Looking At? The Surprising, Shocking, and Sometimes Strange Story of 150 Years of Modern Art by Will Gompertz. Although a good portion of the things in this book are a review for me, I still am learning several new things, which is fun. I also appreciate Gompertz’s humorous and approachable writing style.

This book isn’t without a few minor flaws, however. I am only about a third of the way into the book, but so far I have noticed a few assertions which seem historically unfounded, as well as a quote about Cézanne which was interpreted slightly out of context. But even these slight errors are providing a diversion for me, since they are making me curious in wanting to know more.

One such diversion for me revolved around Gompertz’s assertion that a scene from Frank Capra’s movie It’s a Wonderful Life was influenced by Gauguin’s painting Vision After the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling the Angel). Gompertz points out that the tree in Gauguin’s painting is used to as a compositional device: the tree is set at a diagonal to divide the earthly realm in the lower left portion of the canvas from the heavenly vision in the upper right (shown below).

Paul Gauguin, “The Vision After the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling the Angel),” 1888. Image courtesy WikiArt

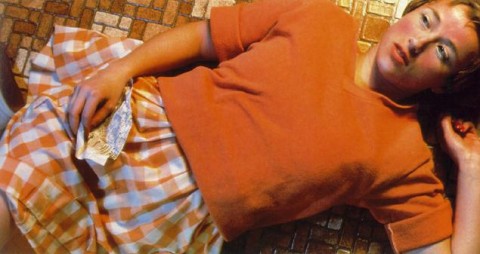

Gompertz then explains that there is a similarity with this composition and a scene from It’s a Wonderful Life. This scene comes just after a pivotal moment in the movie in which George Bailey, who was about to attempt suicide by jumping off a bridge into a river, ended up jumping in the river to rescue the angel Clarence who was drowning.The following scene shows George resting and drying off in a wooden shack with the angel Clarence. Due to the perspective of the camera, some shots of this scene are divided by the diagonal of a clothesline; this line separates the heavenly angel Clarence from the burdened, careworn mortal George Bailey (see below).

Film still from Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946)

I agree with Gompertz that there are compositional and symbolic parallels between Capra’s film and the Gauguin painting. And I appreciate that Gompertz brought this to my attention, especially since It’s a Wonderful Life is one of my favorite movies. My issue, however, is that Gompertz asserts a direct, one-to-one historical relationship between the painting and film. He explicitly states that Capra “referenced this painting” by Gauguin.1 I cannot find any source by Frank Capra or anyone else associated with It’s a Wonderful Life to verify that Capra had Gauguin’s painting in mind when he created his classic film.

Interestingly, though, my research did lead me to find that Capra was interested in Gauguin and his art. Capra’s autobiography, The Name Above the Title (1972), discusses Gauguin at one point. In this section, Capra addresses what some critics could perceive as the “gee whiz!” factor in his films – that is, characters in the films walk around wide eyed, perceiving things as larger than life. Capra defends this “gee whiz” factor by explaining that to some people, “all that meets the eye is larger than life, including life itself.”2 Capra then explains, “Gauguin was a gee whizzer. He painted the South Seas not as he found them, but as he wanted to find them. He created his own South Seas.”3

There is no doubt, then, that Capra thought highly of Gauguin, and it seems like he also liked Gauguin’s paintings, by extension. However, I’m still waiting to find a direct historical connection between It’s a Wonderful Life and Vision After the Sermon, even if a visual connection can be made. If I was writing Gompertz’s book, I would have wanted to point out this visual similarity, but also mention that Capra may have been influenced – either directly or indirectly – by other artistic factors when he considered the set up for this scene with George Bailey and Clarence. I’m particularly reminded of Japanese paintings which use diagonal lines to divide different spaces, such as the division between private and public spheres in a scene from the Tale of Genji (see below).

Gauguin’s Vision After the Sermon was definitely influenced by the Japanese aesthetic, but Gauguin wasn’t the only 19th century artist who was interested in diagonal lines (or even trees-as-diagonal-lines, for that matter – see Van Gogh’s Flowering Plum Tree, which is a copy of a Hiroshige print). So, my guess is that several factors are contributing to Frank Capra’s scene. Does anyone have other thoughts or know more about Capra’s artistic influences as a director?

Also, do you know of other places in which diagonal lines are used to create a strong symbolic distinction between two types of spaces (such as earthly and unearthly, or public and private)? This compositional device is intriguing to me.

1 Will Gompertz, What Are You Looking At? The Surprising, Shocking, and Sometimes Strange Story of 150 Years of Modern Art (New York: Plume, 2012), 66. Source available online as a Google Book: http://books.google.com/books?id=gBXxKol-XVYC&lpg=PT56&ots=fD3Hou_k0j&dq=frank%20capra%20george%20bailey%20gauguin&pg=PT56#v=onepage&q&f=false

2 Frank Capra, The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography (London: W. H. Allen, 1972), 138. Source available online as a Google Book: http://books.google.com/books?id=x_E09IWRomMC&lpg=PA138&ots=31sjkINX8o&dq=%22the%20name%20above%20the%20title%22%20gauguin&pg=PA138#v=onepage&q&f=false

3 Ibid.