Monday, September 24th, 2012

The Farnese Bull and Messy Art History

Although I’m not a specialist in Hellenistic or Roman sculpture, I like to feel like I am pretty savvy regarding the major works of art from these periods. Up until earlier this year, however, I was not familiar with the “Farnese Bull” (shown above). This sculpture, which was excavated in 1545, was soon placed in the Palazzo Farnese as part of the collection of Pope Paul III (formerly Cardinal Alessandro Farnese).

At almost 12 feet (3.7 m) in height, this sculpture has a dominating presence. In fact, the complex composition and large scale made me wonder why I hadn’t seen this work of art in more art history textbooks. Although I have since learned of a few sources which discuss this book (including a great entry in Haskell and Penny’s Taste of the Antique), I still think that this work is underrepresented in art history textbooks geared for college students. And, after doing some research, I think I have figured out why this book isn’t discussed in more: the subject matter, history, and historical reception of this piece are really complex and messy. Taking my cues from Haskell and Penny’s entry, I thought I would outline a few things to prove my point:

- Subject matter: It is hard to concretely say what is being represented in this piece. The Farnese inventory (of 1568) describes this piece as “the mountain with the Bull, and four statues around it.” Vasari tried to take things further and described this piece as a Labor of Hercules. Others believe that this sculpture represents the story of Dirce, the wife of Licus. Dirce hated her niece Antiope and tried to have her killed. However, Antiope’s sons intervened and tied Dirce to a wild bull as punishment.

- Ancient history: It is hard to date this piece. Scholars still debate whether this piece, which was excavated at the Baths of Caracalla, is a Roman copy or an original Hellenistic copy. Some scholars argue that this sculpture was specifically made for Caracalla’s baths (as a Roman copy). Scholars also disagree as to whether this was the work of art that was described by Pliny the Elder: the statue doesn’t quite match the descriptions of a statue which was brought to Rome during the time of Augustus.

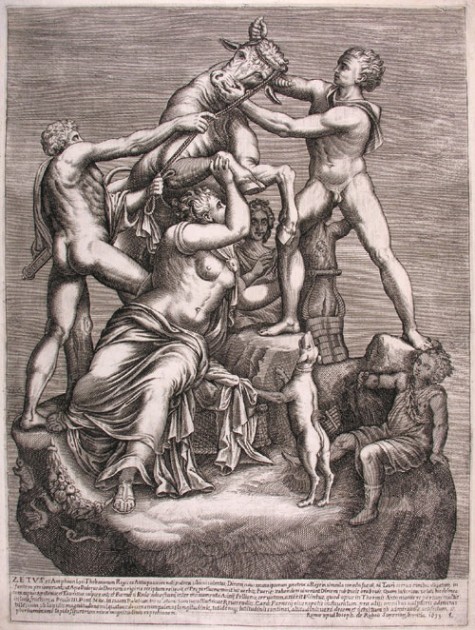

Anonymous Artist "CL", The Farnesian Bull, 1633. Etching.

- Renaissance and Baroque history: It is clear that the Farnese Bull underwent some restorations after excavation, and they may have been completed by Michelangelo and his students (similar to the restorations of the “Farnese Hercules”). The “Farnese Bull” became very well-known in the Renaissance and afterward, popularized in part by prints (see etching above). Federico Zuccaro said that this was “the most remarkable and marvelous work of the chisel of the ancients” In fact, the ostentatious Louis XIV tried to acquire the piece in 1665!

- Criticisms of the work: Despite the original praise for this piece, the “Farnese Bull” began to receive criticism in the 17th and 18th centuries for its lack of quality. Bernini noted that the sculpture was only well-known because it was carved from a single piece of stone and created on a large scale. Other criticisms were more pinpointed. The Richardsons noted, for example, that the rope was of “poor quality.” Edward Wright felt like Dirce’s face was “quite without Passion.” Although Winckelmann was also dismissive of the work, although he did note that the extensive restorations have affected the many opinions regarding the piece.1

So, despite the high praise that this work of art experienced in the Renaissance period, it doesn’t seem to have gotten a lot of attention today from art history textbooks. Is it too difficult for textbooks to introduce “messy” situations to undergraduate students? Perhaps it is tricky at times, but I also think that students are bright enough and capable enough to grasp the complexity of art history. In fact, I think it’s good for them to realize how art history is a compilation of various opinions that have built up over time. (It seems like the omission of this sculpture in art history books is an indication of what is and is not valued today in art history.) I also think that it is a good idea to introduce issues of “quality” to students, so they can think about how the concept of quality is a construct.

Has anyone seen the “Farnese Bull” or one of its copies? What was your opinion of the piece? Also, has anyone seen the “Farnese Bull” treated at length in a traditional (and relatively recent) art history textbook for college students?2 I’d be interested to see how this sculpture is treated in such a text, if it exists. Haskell and Penny’s catalog is great as a scholarly resource, but I’m not sure if it is very practical as a textbook for a college course.

1 Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500-1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982), 165-167. Citation available online HERE.

2 I did find one online academic source which discusses the Farnese Bull at length, but quotes an art history textbook by Gisela M. A. Richter which was written in 1930!

I visited the Farnese, but I don’t remember seeing this piece at all! 🙁

I’m not sure I agree that the complex and messy history is the reason for it not receiving as much attention as, say, the Farnese Hercules, though. There are lots of pieces with complex histories or mysterious depictions that receive TONS attention–the Mona Lisa for one. I think scholarly research feeds on itself like an ouroboros and the more research and print about a piece, the more that’s written about it. Maybe you can start a rebirth of scholarship in the Farnese Bull, though. 🙂

Hi M! Fascinating post once again. I love your perennial curiosity for the quirks and oddities of art history!

I am wondering if there is a more practical explanation to the lack of coverage other than its messiness. To cite a relevant example in painting, Giorgione’s “Tempest” or Titian’s “Sacred and Profane” have had liters of real and virtual ink spilled trying to figure out what they mean. There are some concrete facts in each case, but not much else to go on – and it is difficult to describe these works on their own without bringing in other more concrete examples to solidify a point.

Yet, looking at an epic hunk of sculpture like the Farnese Bull, the commentator must achieve the daunting task of being familiar with the Renaissance/Baroque context, the Roman adaptation of Hellenistic models, and then go back to the Hellenistic roots themselves (along with their antecedents) Is there such a superhuman art historian out there? There may be – but I have not met them yet?!

A slightly tangential, but relevant example is the study of perspective. For so long it has been a field for an esoteric branch of historians of science, mathematics and art to ponder (almost) purely in a late Medieval/Early Modern context. Yet there was *something* happening in regarding depictions of a type of perspective in the ancient world, evidenced by relief sculpture, extant frescoes and important works like Euclid’s optics. Yet despite this, the literature on Roman perspective is comparatively much less developed.

Hence, such questions surely come down to the logistics of study? People end up specialising in niches and interdisciplinary projects with a broad scope to tackle such inter-era overlap are not very common.

I’m interested to hear what others think – and hope some specialists on ancient sculpture may chime in too.

An interesting topic!

H

I think you’re right that it’s relatively absent from standard undergradute texts: the ones I have here seem not to mention it, with the exception of RRR Smith’s Hellenistic Sculpture: A Handbook (London : Thames and Hudson 1991), which illustrates it as plate 142 and discusses it (typically for this series) briefly on p. 108; and John Onians’ Art and Thought in The Hellenistic Age: The Greek World View 350-50 BC (London : Thames and Hudson 1979), pp. 90 and 92, illustration 93.

@heidenkind and H Niyazi: Your comments have made me think about how the complicated subject matter probably is not as much of a deterrent to art historians. Out of all of the factors that I mentioned, subject matter is the least daunting or off-putting. You’re both right: plenty of complicated or enigmatic works of art exist. I do think, though, that with all the other complicated historical factors regarding this piece, the ambiguous subject matter might not help the piece get more discussion.

H, I also think that you brought up a good point about the complicated history between this work of art, since it involves both ancient and early modern history. Although I’m sure there are some art historians who like to dabble in both of these areas, I think that it is less common.

I’m particularly intrigued by how the piece gradually changed in its “status” somewhere between the Renaissance period and the Baroque/Neoclassical periods. Public perception obviously changed dramatically if Louis XIV wanted to acquire this sculpture in the 17th century, and then later writers like Winckelmann are derisive of the work. (If Louis XIV had acquired this sculpture, would it have received more positive attention in later centuries? Perhaps?) It seems to me that all of the observations about the “poor quality” of the sculpture have affected what attention has been given to this piece in recent centuries. People seem to have dismissed the work, and others followed suit.

@Terrence Lockyer: Thanks for mentioning these two books! I’ll have to look into them, just to appease by curiosity. I wonder if anything has been published on the “Farnese Bull” more recently than 1991.

Great post! I have always loved this piece, but I think that is largely because of its monumentality and how I imagine it to have appeared in Caracalla’s baths. Bruni Ridgway does a nice rundown on the piece and its history in her Hellenistic Sculpture II as I recall.

I loved your post but I must admit I was a bit puzzled. I am not a student of art history yet the Farnese bull has always been sort of ‘given’. I know about its existence like I know about the Last Supper – I do not know how, when, where I first heard of it but it has always been part of my knowledge. Perhaps it was on the cover of our history book in high school. But I strongly feel it is fairly known in Europe even among the general public.

Maybe it is just a problem of geography; it is in Italy and those visitors who reach Naples (sadly) often miss the Museum. So if you feel that it is not part of mainstream art history, maybe it is just because of some very pragmatic issues like location and knowledge of it by the general population.

I happened to see it in Naples and I believe there are a few engravings around which feature it in its original location (I believe I saw some images in the Museo di Roma). Also, approximately a year and a half ago the Palazzo Farnese (now the bloody French Embassy) was open for visitors and I think they featured various images of the statue to emphasize the fact that it was originally in the palace.

I have no knowledge if it is part of any student books or the general curriculum for art history students. But I am in complete agreement with you that it could have its place in art history courses. I think your arguments highlight a very important point about art history in general – that the history of any object is always ‘a work in progress’; we can never know for sure what happened and history is always subject to interpretation. And today’s viewer can always add extra layers to a piece’s history. All which can highlight the complex and unknowable nature of the field.

On a very personal note; when I first saw the statue the idea to categorise my museum pictures by their original location occurred to me. Now every time after a museum visit I organise my pictures and put them in folders based on their original location. I mean the statues, mosaics and other artifacts of the grand buildings of ancient or Renaissance Rome live in ‘Diasporas’ in the great museums of the world. So when I see them, I take pictures and I put in the folders such as ‘Terme di Caracalla’, ‘Temple of Isis’ etc. This way when I actually visit a location, I can just look them all up on my iPad/iPhone – it is so much easier to visualise what the places must have felt like. Sorry, this was a very personal remark but I was first inspired to do this when I saw the Farnese Bull. 🙂

More please!!!

Nice article, thanks for the information.

Hi A.M. Christensen! Thanks for your comment. I’ll look into the book “Hellenistic Sculpture II” and see if I can find more discussion on the Farnese Bull. Thanks!

Hi Zsuzsi! Thanks for your wonderful comment. It was really interesting to hear about how this statue (and your first interaction with this statue) has influenced you.

Perhaps American (or English speaking?) art historians are less familiar with this piece than the European public. That is an interesting point. If I delve into this topic further, I would want to see if there are more publications on the Farnese Bull that exist in Italian (or another European language other than English).