Friday, July 6th, 2012

Intentional Damage: The “Night Watch” and Temple of Artemis

I don’t like it when works of art get damaged (not by any means!), but I’m intrigued when such catastrophes occur. I’ve blogged about this topic before, discussing instances when Michelangelo’s Pietà and Malevich’s Suprematism (White on White Cross) were damaged by mentally-unstable individuals. (I’ve even decided to start an “intentional damage” label for these kinds of posts.)

I wanted to write about two works of art/architecture that have been intentionally damaged over time. The following two works of art may seem unrelated to most, but they are connected in my mind: I learned more about the damage done to these works during my recent trip to Europe. I had an extended layover in Amsterdam and got to visit the Rijksmuseum (where I saw Rembrandt’s The Night Watch) and finished my trip in Selçuk/Ephesus, where the Temple of Artemis is located.

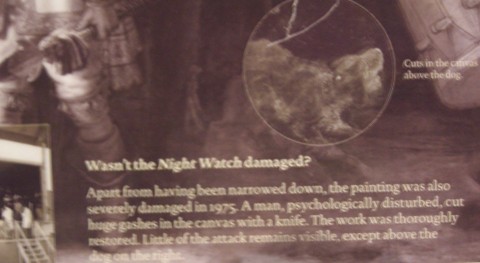

When visiting the Rijksmuseum, I was reminded that “The Night Watch” was greatly damaged in 1975, when a mentally-unstable school teacher, Wilhelmus de Rijk, slashed the painting with a bread knife. You can see some of the initial damage in the following YouTube clip. Don’t those slashes just pull at your heart strings?

Although the 1975 incident is the most famous example of damage to Rembrandt’s masterpiece, there are actually a few other times in which the “Night Watch” has been attacked. An unemployed shoemaker slashed the painting during World War I, to protest his inability to find employment. (Which is so ridiculous! Who would want to hire someone who just slashed a priceless painting?)1 In April 1990, it was reported that a jobless Dutchman sprayed an unknown chemical substance (later determined to be acid) on the painting, but luckily the damage was minimal. (Note: The Rijksmuseum’s site also mentions that the painting was sprayed with acid in 1985, but I think that this date is actually referring to the 1990 event.)

Detail of "Night Watch" text label from Rijksmuseum, showing the area where evidence of the 1975 damage is still seen on the painting

The other intentionally-damaged art that I recently learned about is the Temple of Artemis, near Ephesus. Before my trip, I already knew that this structure (which was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World) is now a ruin (see below).2 However, I didn’t realize that this structure was burned in 359 BC, by an allegedly mentally-unstable person named Herostratos (also spelled Herostratus) who hoped to make his mark on history.3 Interestingly, this fire was also said to occur on the same night that Alexander the Great was born. Although there isn’t a way to verify that the fire took place on this exact date of July 20th or 26th (beyond what is mentioned in historical writings), archaeologists have noted that the some ruins from the site bear traces of fire.4

Herostratos was executed for his crime, and the Ephesians also created a decree to ban the mention of the Herostratos’s name. Obviously, the ban was not followed, since the story has been recorded by historians like Theopompos of Chios.

Parts of the ruined temple later were used to help build the nearby Basilica of Saint John. So, I guess, in some ways you can go and see some of the Temple of Artemis when you are in Selçuk, although the materials have been reconfigured to help form a different religious structure!

Ruins of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (modern Selçuk), Turkey (begun 8th century BC)

In November 2011, plans were announced to build a $150 million reconstruction of the Temple of Artemis. I didn’t hear anything about this reconstruction while I was in Turkey, which makes me wonder if the project received funding. If the temple does get rebuilt, though, we’ll need to make sure that arsonists stay away!

Want to read about more damaged art? Artdaily has compiled a good list. Do you know of more examples of intentionally-damaged art? Does anyone have a thought as to why mentally-unstable people would be drawn to damage art (as opposed to something else)?

1 In many respects, Rembrandt’s painting is actually “priceless.” Although the members of the civic guard paid Rembrandt 1,600 guilders back in the 17th century, there is no other price attached to this piece. The museum does not insure the painting (it is in loan from the city of Amsterdam), in accordance with Culture Ministry policy.

2 Several temples were built on this site over time. A few reconstruction of the temple are found HERE and HERE.

3 Albert Borowitz, Terrorism for Self-Glorification: The Herostratos Syndrome (Kent State University Press, 2005), 4 – 19. Citation can be viewed online HERE. This citation also follows the historiography of a allegation that Herostratos burned the Temple of Artemis on the same night that Alexander the Great was born.

4 Ibid., p. 5. Citation can be viewed online HERE.

I’m curious about the term “intentional damage,” which sounds to me like a deliberate substitution for a simpler word more often used for this kind of expression: vandalism. Is there a difference between “vandalism” and “intentional damage?” Does vandalism carry unnecessarily restrictive criminal connotations? Is there a desire to avoid a pejorative link to the fifth-century East Germanic tribe? Because I can understand if that would be politically incorrect.

Hello M! Another interesting post.

In your account of both events, I see that you did pass on the descriptions of both perpetrators as in a state of relative mental distress – and this is the key to understanding why these things happen.

It is very easy to gloss over this point – but an understanding of the psychology of people who do these things would assist with training of museum staff to prevent these things from happening in the future. We should be weary of being judgemental of someone whose circumstances and state of mental health we can not understand. These objects become “soft targets” for making a statement, or even as a cry for help, or a publicity stunt (as seen in the recent defacing of a Picasso by a street artist or the theft and return of a Dali).

It is unfortunate but ultimately comes down to the great fame and attention payed to particular artists, sites or works of art. The psychology of those who perpetrate these type of crimes (and art crime in general) is very sparsely documented, and could do with further research to inform not only museum/gallery staff, but also the genera public visiting these places.

@ Jon – fear of offending a long gone East Germanic tribe with “Vandalism” is taking political correctness a bit far isn’t it! I would think the words are functionally synonymous – I do like the clarity of “intentional damage” – though it must be mentioned – are the people who do these things aware they are “damaging” the works – this may not necessarily be the case in all instances.

Kind Regards

H

H Niyazi –

I admit the part about the Germanic Vandals was a joke. Nevertheless, political correctness can be and has been carried “too far” in the past, so it wasn’t entirely out of the realm of possibility!

I still wonder however, if “intentional damage” communicates something about the deliberateness of a vandal’s actions which “vandalism” does not? Is it possible to vandalize something inadvertently?

@Jon: In this instance, I didn’t even think of the word “vandalism” when writing this post! I don’t really have issues if that word is used with more frequency (whether or not it refers to an East Germanic tribe – ha!). I think that my subconscious shies away from the word “vandalism” at times, simply because (in my own mind) I feel like that word often connotes a maliciousness that might not have been felt on the part of a mentally-unstable person. That being said, I realize that “intentional damage” is also a little tricky. As H Niyazi mentioned, some of these people might not be aware that they are “damaging” a work of art. (But I do feel like “intentional damage” is more appropriate in these instances than, say, “circumstantial damage”).

I do think, though, that “vandalism” is very appropriate to use in many other cases, like when Alexander Brener spray-painted a dollar sign on a painting by Malevich.

@H Niyazi: You have brought up some good points. I actually didn’t discuss the mental instability of the perpetrators in depth, simply because (as you mentioned) there isn’t much documentation on this topic. It seems like there could be more research on this issue, especially so we can better understand issues of mental health. When researching this post, I came across the book “Terrorism for Self-Glorification: The Herostratos Syndrome”. Although this book seems to approach vandalism and terrorism from a historical standpoint, it might delve into issues regarding mental health.

Excellent post.

Related – kind of: the first photo here is an example of intentional damage as an integral process of making contemporary art.

http://www.edwardwinkleman.com/2012/07/opening-tonight-painting-is-history.html

Thanks for the link, Ebriel! That exhibition looks very interesting. I do think that intentional damage is a key part to contemporary (and even modern) art. That exhibition reminded me of other artists who intentionally damage canvases, like Lucio Fontana. Perhaps I’ll have to explore this idea further in another post!