Saturday, March 26th, 2011

Mrs. Arnolfini Might Be Dead!

Yes, the title of my post is a bit facetious. Of course Mrs. Arnolfini is dead – Jan van Eyck’s famous Arnolfini Portrait (shown left, 1434) was made several centuries ago. But I’m actually referring to a relatively new argument: in 2003 Margaret L. Koster argued that this double-portrait includes a depiction of Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini’s deceased wife.1 (Koster recognizes though, that this painting might not be of Giovanni Arnolfini at all – there were no less that five Arnolfinis in Bruges at the time who could have commissioned the painting. In 1998 Lorne Campbell picked Giovanni di Nicolao as the probable commissioner for this painting, since Giovanni di Nicolao would have been in Bruges for some time and would have had ample opportunity to meet Jan van Eyck.2)

Anyhow, I think Koster’s argument is fascinating for several reasons. First of all, Koster reveals an archival discovery that Giovanni di Nicolao’s wife, Costanza Trenta, was dead by 1433 (a year before the Arnolfini Portrait was dated!). And from what we know, Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini never remarried.

So, what does this mean? Koster convincingly argues that this portrait is a posthumous representation of Costanza, a way to remember and commemorate Giovanni’s wife. The oath gesture by Arnolfini could reference an wedding oath already taken, perhaps suggesting a renewal of Arnolfini’s wedding vows and devotion to his deceased wife.

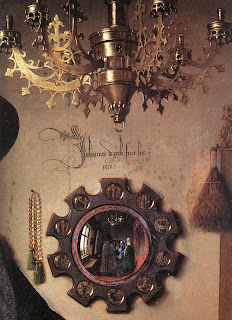

First of all, the idealized depiction of Costanza stands in stark contrast to the very naturalistic and individualized depiction of Giovanni, which could indicate that these two individuals are separated by life and death. Furthermore, there are other aspects in the painting which allude to death. The roundels circulating the mirror frame (see right) are scenes from the Passion of Christ. All of the scenes which show Christ alive are on the left side of the mirror (near Giovanni), whereas all of the scenes alluding to Christ’s death or resurrection are closest to Costanza. Additionally, the lit candle is placed near Giovanni, whereas the snuffed-out candle is placed over Costanza.

The colors of Costanza and Giovanni’s garments could also symbolically allude to their present situation. Costanza is wearing a dress of blue and green: blue was a symbol of faithfulness and green was a symbol of love. Giovanni’s darker clothing can be interpreted as a symbol of mourning or suffering (and Koster further points out that this work was painted before black clothing became fashionable for the Burgundian court).

If you’d like to see Koster explain aspects of her argument, check out the beginning of the “Part 5” section for this documentary. (This documentary on Northern Renaissance art is hosted by Joseph Koerner, another art historian who happens to be Margaret L. Koster’s husband!).

What do people think of this argument by Koster? On a side note, I have to say that I’m always surprised when practicing scholars still refer to this painting as a wedding portrait. That Panofskian approach has been questioned by Northern Renaissance scholars for several decades, and even the National Gallery (which houses this painting) shies away from the wedding interpretation. In fact, I thought the wedding debate was settled in 1993 by Margaret D. Carroll, who pointed out that Mrs. Arnolfini is wearing a headdress traditionally reserved for married women.3 Argh. Despite all of the respect that Panofsky deserves, I really feel like we need to stop interpreting this piece as a wedding portrait. Let’s get on with our lives, folks.

1 Margaret L. Koster, “The Arnolfini Double Portrait: A Simple Solution,” in Apollo (Sept. 2003): 3-14. Text available online here.

2 Lorne Campbell, “Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife,” The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Schools (London, 1998), 174-204 (see especially p. 195).

3 Margaret D. Carroll, “In the Name of God and Profit: Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait,” Representations 44 (Autumn 1993): 100-101.