Thursday, December 29th, 2011

Let’s Reconsider (and Republish on) the “Well of Moses”

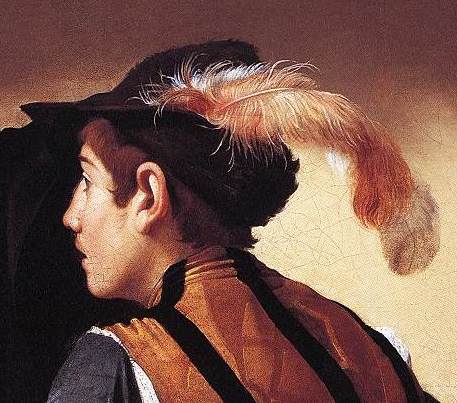

Claus Sluter, detail of David and Jeremiah from the "Well of Moses," 1395-1406. Chartreuse de Champol, Dijon. Image courtesty simonsara via Wikipedia.

I didn’t plan on spending my winter break rooting out an error in Stokstad’s Art History textbook. I promise! I just happened upon this error when looking for more information about the lost Calvary composition, which was originally part of Claus Sluter’s “Well of Moses” (1395-1406). In truth, the “Well of Moses” originally served as a base for a large sculptural composition, which included a crucifix. Today’s “Well of Moses” is just a shadow of the original work produced by Sluter. On a side note, you may find it interesting that the “Well of Moses” is a relatively recent nickname for this work of art, having first been used in the late 18th century. Instead, early sources refer to this monument as “The Cross” or “The Great Cross.”1 From what I can gather, the original crucifix composition largely was destroyed in 1791, during the French Revolution. One can get a general sense of how the “Well of Moses” appeared by looking at a 16th century copy that is located at the Hôpital Général in Dijon, although there are no figures included with the Calvary scene (see below).

Copy of the "Well of Moses" group, 1508, Hôpital Général, Dijon. The cross is a nineteenth century reconstruction. Image available on Wikipedia via Christophe.Finot

Anyhow, Marilyn Stokstad’s recent art history book points out that that the Calvary group on top of the “Well of Moses” included three figures at the base of the crucifix: the Virgin Mary, John the Evangelist, and Mary Magdalene.2 In the mid 19th century, a model of the Well of Moses was created by Joseph Moreau which showcased these three figures at the base of the crucifix. (It should be noted that sculptural fragments of Christ and Mary Magdalene both exist, but there never have been any fragments found of John the Evangelist or the Virgin Mary.)

I am disappointed that Stokstad’s Art History does not take recent research on the “Well of Moses” into account. A study published in 2005 reveals a very different (and unexpected) result of the crucifix composition. As part of a three-part series of articles on the “Well of Moses,” Susie Nash (of the Courtauld Institute) points out that the Calvary composition only depicted one figure at the base of the cross: Mary Magdalene.3 During the relatively recent restoration of the “Well of Moses” (a fifteen year project that ended in 2004), Nash was able to analyze the top of the “Well of Moses,” including the original mount for the crucifix. Nash also analyzed the remaining fragments from the Calvary composition, too, including the arms of Mary Magdalene. Nash concluded that the composition of the remaining base and extant fragments reveal that only one figure was located at the base of the cross. She also concluded, based on the fragments of the Mary Magdelene figure’s arms, that the Magdalene was originally embracing the foot of the cross. She supports her argument which archival evidence too, including an 18th century drawing of the Hôspital Général “Well of Moses” copy (see below).

Maurice Bauthélier, "La Belle Croix," c. 1760. Drawing of the 16th century copy of the "Well of Moses," located at the Hôspital Général in Dijon

Although there are some problems with this 18th century drawing (the figure depicted has short locks instead of the flowing, long hair of the Magdalene), it seems pretty obvious that the crucifix composition did not originally include figures of the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist. (Nash concludes her 2005 article by promising to discuss later how the crucifix itself also appeared differently than usually supposed. This topic ended up being the premise for the article, “Claus Sluter’s ‘Well of Moses’ for the Chartreuse de Champol Reconsidered: Part II,” published by Nash in July, 2006.)

In some ways, perhaps I shouldn’t be too hard on Stokstad for mentioning three figures at the crucifix base instead of just one. Nash herself points out, “The belief that Sluter’s Calvary had three figures is so entrenched in the scholarly literature of the last 160 years that their existence has never been questioned.”4 But, as I have said before, I do feel like such a major art history textbook should be better at keeping up with current scholarship. Is Stokstad’s Art History so confidently “entrenched” that it doesn’t feel the need to include groundbreaking ideas? Omissions like Nash’s scholarship on Sluter reinforce to me that Stokstad’s book is not “the most…inclusive art history text on the market.” Although I think there are some great things about that textbook, I don’t think that Art History should be the art historian’s bible.

P.S. Don’t forget that my giveaway on the Irene Duclos book ends tomorrow!

1 Susie Nash, “Claus Sluter’s ‘Well of Moses’ for the Chartreuse de Champol Reconsidered: Part 1,” The Burlington Magazine 147, no. 1233 (December, 2005): 798. Article available online on Nash’s faculty webpage. I have translated the contemporary sources from French, which read “la croix” or “la grant [sic] croix.”

Marilyn Stokstad and Michael Cothren, Art History, vol. 4 (Prentice Hall, 2011), p. 564.

3 Nash, 799, Susie Nash also has two other publications on the Well of Moses, which were published in The Burlington Magazine in July 2006, pp. 456-67 (Part II) and November 2008, pp. 724-741 (Part III). These two articles are also available on Nash’s faculty webpage.

4 Ibid., 799.