Friday, February 10th, 2012

To Hack Off a Leg: Michelangelo’s Florence “Pietà”

Several months ago I wrote a post on Michelangelo’s Florence Pietà (also called the “Bandini Pietà” or “Duomo Pietà”). Back then, I promised to explore in a future post some of the reasons why Michelangelo might have mutilated this sculpture (which originally was intended for the artist’s own tomb). When I promised to write this post, I didn’t realize that I would be opening a big can of worms! I’ve spent several hours combing through a lot of research and ideas – and to tell the truth, I still haven’t completely formed an opinion about what I find the most compelling.

Although I wrote down a lot of information in a lengthier draft of this post, I’ve decided to condense a few thoughts here. (If you want to see more research or a semi-detailed historiography of mutilation research, contact me!)

Our good ol’ friend Vasari gives several contradictory suggestions for why the sculpture was mutilated: 1) the marble contained flaws; 2) the marble was too hard, and sparks would fly from the chisel; and 3) Michelangelo’s standards for the piece were too high, and he was never content with what he had completed. (This last suggestion seems like a musing on Vasari’s part.) Vasari also explains that Michelangelo was pressured to work on the piece: “It was because of the importunity of his servant Urbino who nagged at him daily that he should finish [the Pietá]; and that among other things a piece of the Virgin’s elbow got broken off, and that even before that he had come to hate it, and he had had many mishaps because of a vein in the stone; so that losing patience he broke it, and would have smashed it completely had not his servant Antonio asked that he give it to him just as it was.”1 In the end, Michelangelo lets his pupil, Tiberio Calcagni, restore the group. As we will see, the left leg may or may not have needed restoration before Calcagni got his hands on the sculpture.

Many scholars in the 20th century have interpreted this mutilation to include the removal of Christ’s left leg, which appears to have been created to hang across the thigh of the Virgin. (An eighteenth-century wax model of the sculpture gives in indication for how it may have originally appeared.) Some scholars, such as Henry Thode (1908), feel that the mutilation may have been done for compositional purposes; the sculpture might have appeared to unattractive and cluttered with the left leg.2

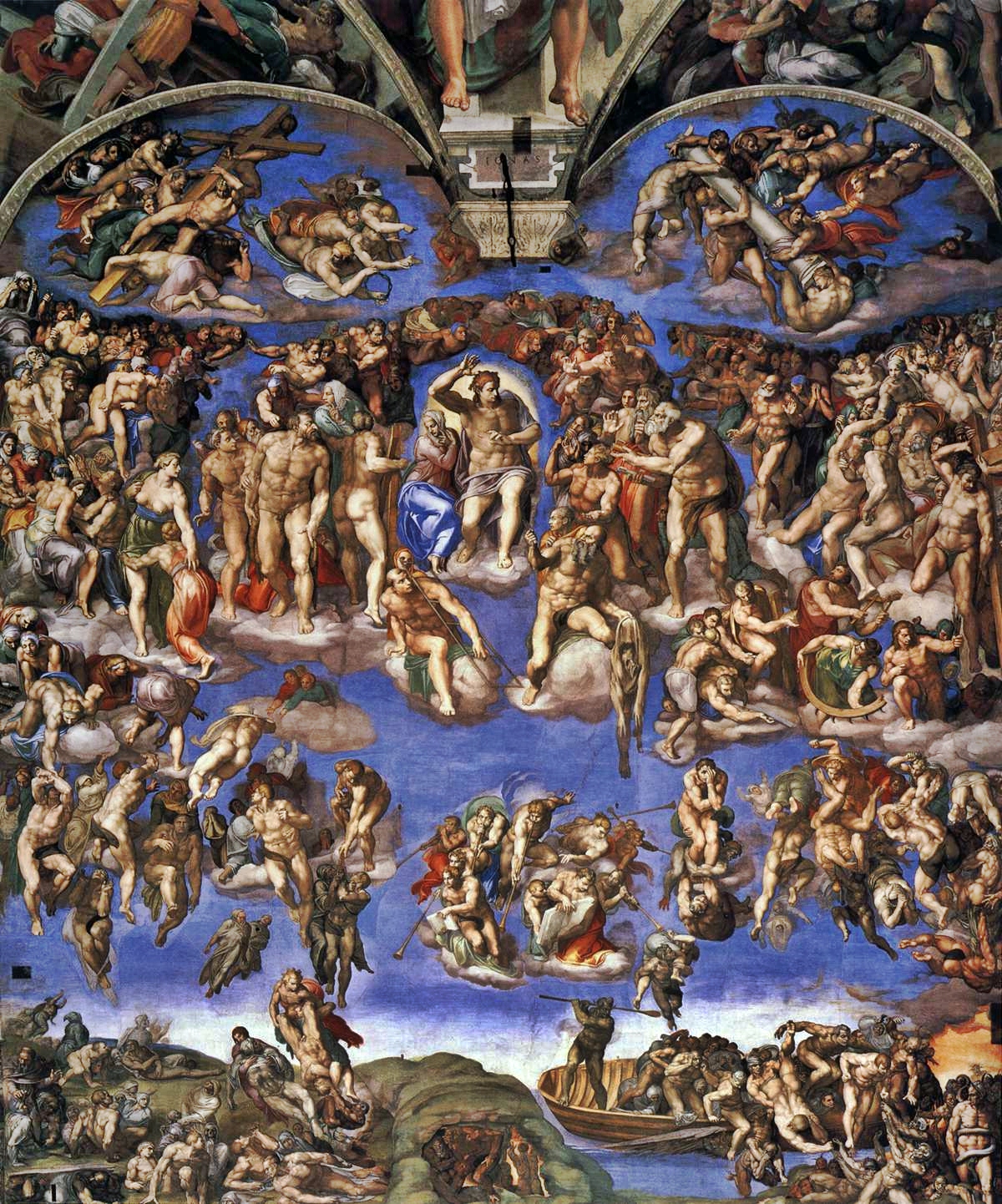

In 1968, Leo Steinberg wrote an interesting (and controversial) article about “the missing leg” of the Florence Pietà. Steinberg argues that the left leg originally existed and was slung over the Virgin’s thigh, as a solemn symbol of a sexual union (a motif that is found in later sixteenth- and seventeenth-century art). Such a composition would have emphasized the symbolic and mystic marriage between the Virgin and Christ. However, it could be that the vulgarization of this motif (during the very years of Michelangelo’s work on this piece) and metaphor might have threatened the symbolic significance that Michelangelo sought.3 For that reason, Michelangelo may have become frustrated and attacked that specific part of the statue. Steinberg got much criticism and was misinterpreted on some accounts, which he explores in twenty years later in another essay (see third footnote).

The most recent and seminal writing on the Florence Pietà was published in English in 2003 by Jack Wasserman. This book unfortunately is out-of-print, but I was able to snag a lonely (yet very deserving!) copy at my university library. Wasserman has issues with Steinberg’s argument on a few levels, but basically argues that the placement of Christ sitting or reclining on the Virgin’s lap does not constitute an “aggressive” action.4 Wasserman gives the example of Caroto’s Pietà (c. 1545) as another example of an “unadulterated Pietà, without, that is, the carnal and symbolic accretions Steinberg imposes on it.”

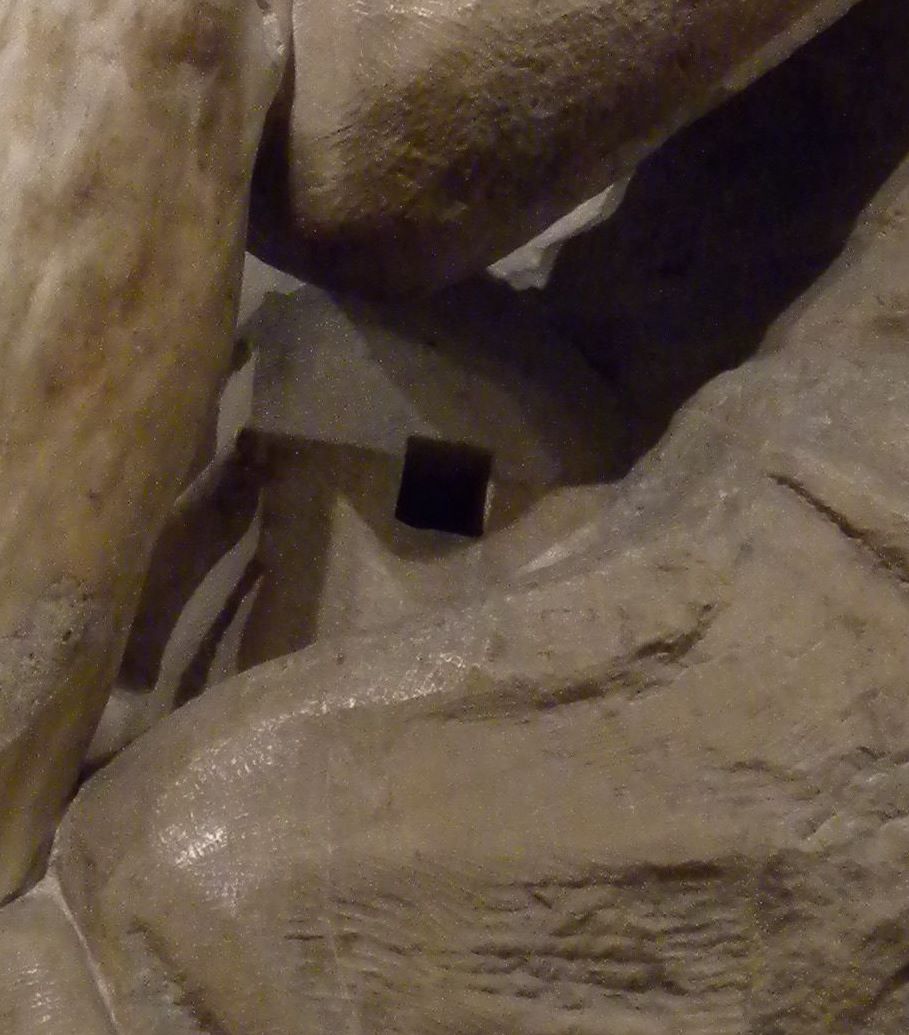

Wasserman also cautiously suggests that Tiberio Calcagni might have actually been the one to remove the left leg of Christ (foot, thigh and calf) as he went about restoring the rest of the statue. Wasserman then finds, in turn, that Calcagni did not succeed in his attempt (or perhaps never attempted) to replace the limb. Calcagni may have created the stump (and the visible drilling hole, see above) with the intention of adding/reattaching a limb, but no traces of binding stucco have been found in the dowel hole. Wasserman even posits that Calcagni might have contrived the story that Michelangelo intended to destroy the Pietà (as reported by Vasari). Instead, “Calvagni desired to benefit from the fact that Michelangelo had broken away several other parts of the Pietà to disguise his own guilt for having demolished Christ’s leg without replacing it, thereby irrevocably disfiguring the great work of art.”5

The other interesting thing about Wasserman’s book is that he discusses how the several limbs of the sculpture were intentionally severed. Wasserman finds that the outlying limbs were removed in an effort to recarve the marble, not destroy the statue. Wasserman believes that Michelangelo used a point chisel to first remove Christ’s and the Virgin’s left arms, and then the right arm of the Magdalene. Then Michelangelo removed Christ’s right forearm, but left the Mary Magdalene’s head without damage.

With this new, practically limb-less marble, Michelangelo gained access to the reserve marble just left of the Virgin’s leg, in order to “excavate” a new left leg for Christ that would parallel the angle of Christ’s right leg.6 Perhaps, considering this new design, the Florentine Pietà might have more closely resembled Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pietà (1564).

1 Vasari, Lives of the Artists (1568 edition), as translated in Leo Steinberg, “Michelangelo’s Florentine Pietà: The Missing Leg,” Art Bulletin 50, no. 4 (1968): 347.

2 Steinberg, 347.

3 Henry Thor, Michelangelo und das Ende der Renaissance, as translated in Leo Steinberg, “Michelangelo’s Florentine Pietà: The Missing Leg Twenty Years After,” in Art Bulletin 71, no. 3 (Sept, 1989): 503.

4 Jack Wasserman, Michelangelo’s Florence Pietà (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 84.

5 Ibid., 84.

6 Ibid., 70.