If you were/are an artist, what would induce you to destroy some of your completed art?

If you were/are an artist, what would induce you to destroy some of your completed art?

A change in taste?

Embarrassment?

Anger?

I am continually surprised and saddened when I think of the Early Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli and his decision to burn some of his paintings.

Sandro Botticelli is arguably the most famous painter of the Early Renaissance. Today, he is probably best known for his mythological paintings The Birth of Venus (c. 1485, shown to the right) and Primavera (c. 1478). These paintings were influenced by International Style, as shown by the ornamental patterns (e.g. Flora’s dress on the right) and unrealistic stylization (e.g. the flat sea waves). Both paintings were completed during the beginning of Botticelli’s career, when he was highly successful and enjoyed the patronage of important families such as the Medici and Vespucci.

However, it appears that Botticelli’s career took an interesting turn with the rise of Girolamo Savonarola, an Italian friar and preacher. Savonarola’s fundamentalist ideas regarding politics and religious art had considerable influence on Florence. In fact, many people in Florence considered Savonarola to be a prophet and type of savior for the city.1 In regards to art, Savonarola condemned the worldly character of religious paintings and criticized artists for using identifiable people as models for holy figures. Savonarola “complained that the images in the churches of the Virgin, St Elizabeth and the Magdalene were painted like nymphs in the likenesses of the young women of Florence, thundering: ‘You have made the Virgin appear dressed as a whore’. In his sermons he upbraided the young women of Florence for wearing such dress and castigated painters for representing them in sacred guise, urging everyone to burn their copies of the Decameron and all lascivious images.”2 There is no doubt that Botticelli’s mythological paintings would have been viewed as “lascivious” by Savonarola, particularly The Birth of Venus, which was the first painting of a Classical female nude since antiquity.

Savonarola convinced many people to burn their worldly items. He is particularly associated with two public burnings took place on 7 February 1497 and and 27 February 1498. These fires are known as the bruciamenti delle vanità (bonfires of the vanities). At these public bonfires, cosmetics, false hair, playing cards, profane books and paintings were destroyed. It’s shocking to think of what precious works of art were destroyed at this time – especially works by the talented Botticelli. According to the biographer Vasari, Botticelli was affected by the teachings of Savonarola and reportedly threw some of his own paintings on pagan themes into the flames. How tragic! I have often wondered what those paintings were like and what type of contribution they might have made to the field of art history.

Of course, Savonarola did not condemn all types of art. He felt that art could be utilized as a type of moral instruction and encouraged his illiterate followers to ponder the life of Christ by looking at paintings (no doubt, paintings which met his level of standard). At this same time, and probably not coincidentally, Botticelli’s artistic style began to change. He began to reject the courtly, ornamental style of his earlier paintings and turned to a more somber, simplistic style which mimicked the sentiment and style of earlier religious paintings. One such somber painting is Botticelli’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ with St. Jerome, St. Paul and St. Peter (c. 1490). Not only is the extense grief and mourning observed in the faces of the figures, but the sweeping lines of the dead corpse and kneeling figures suggest to me an added level of heaviness, weight, and grief.3 I cannot help but conclude that this shift in style was influenced by Savonarola’s apocalyptic preaching.4

Of course, Savonarola did not condemn all types of art. He felt that art could be utilized as a type of moral instruction and encouraged his illiterate followers to ponder the life of Christ by looking at paintings (no doubt, paintings which met his level of standard). At this same time, and probably not coincidentally, Botticelli’s artistic style began to change. He began to reject the courtly, ornamental style of his earlier paintings and turned to a more somber, simplistic style which mimicked the sentiment and style of earlier religious paintings. One such somber painting is Botticelli’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ with St. Jerome, St. Paul and St. Peter (c. 1490). Not only is the extense grief and mourning observed in the faces of the figures, but the sweeping lines of the dead corpse and kneeling figures suggest to me an added level of heaviness, weight, and grief.3 I cannot help but conclude that this shift in style was influenced by Savonarola’s apocalyptic preaching.4

Unfortunately, Botticelli’s career faltered near the end of his life, which is especially disappointing since the artist was originally one of the influential painters in developing the new Renaissance style. I find the demise of Botticelli’s career partially linked to Savonarola and the artist’s subsequent change in style.

I wonder if Botticelli held any regrets about burning his paintings or his change in artistic taste. Savonarola’s followers were often referred to as piagnoni (“snivellers” or “weepers”) because “they were given to loud and weepy repentence for their sins.”5 It is known that Botticelli’s brother was a piagnone and there is other evidence that Botticelli was also associated with this mournful group.6 If I were Botticelli and had burned some of my beautiful art, it seems like I’d have an additional reason to weep.

1“Savonarola, Girolamo.” In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.erl.lib.byu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T076215 (accessed February 5, 2009).

2 Charles Dempsey. “Botticelli, Sandro.” In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com.erl.lib.byu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/art/T010385 (accessed February 5, 2009).

3 For more analysis of this painting and Savonarola’s influence on Botticelli, see Barbara Deimling, Botticelli, (New York: Taschen, 2000), 69-72. These pages can also be read online here.

4 Not all historians agree on Savonarola’s influence on Botticelli. For some discussion on the art historical debate between Savonarola’s influence on Botticelli, see Ingrid Drake Rowland, From Heaten to Arcadia: The Sacred and the Profane in the Renaissance, (New York: New York Review of Books, 2005), 80-81.

5 Ibid, 80.

6 Vasari records that Botticelli was “extremely partisan to [Savonarola’s] sect.” See Dempsey, “Botticelli, Sandro.”

St. Fredianus Diverts the River Serchio, c. 1438

St. Fredianus Diverts the River Serchio, c. 1438 Madonna of Humility (Trivulzio Madonna), c. 1430

Madonna of Humility (Trivulzio Madonna), c. 1430 Detail of Disputation in the Synagogue, 1452-65

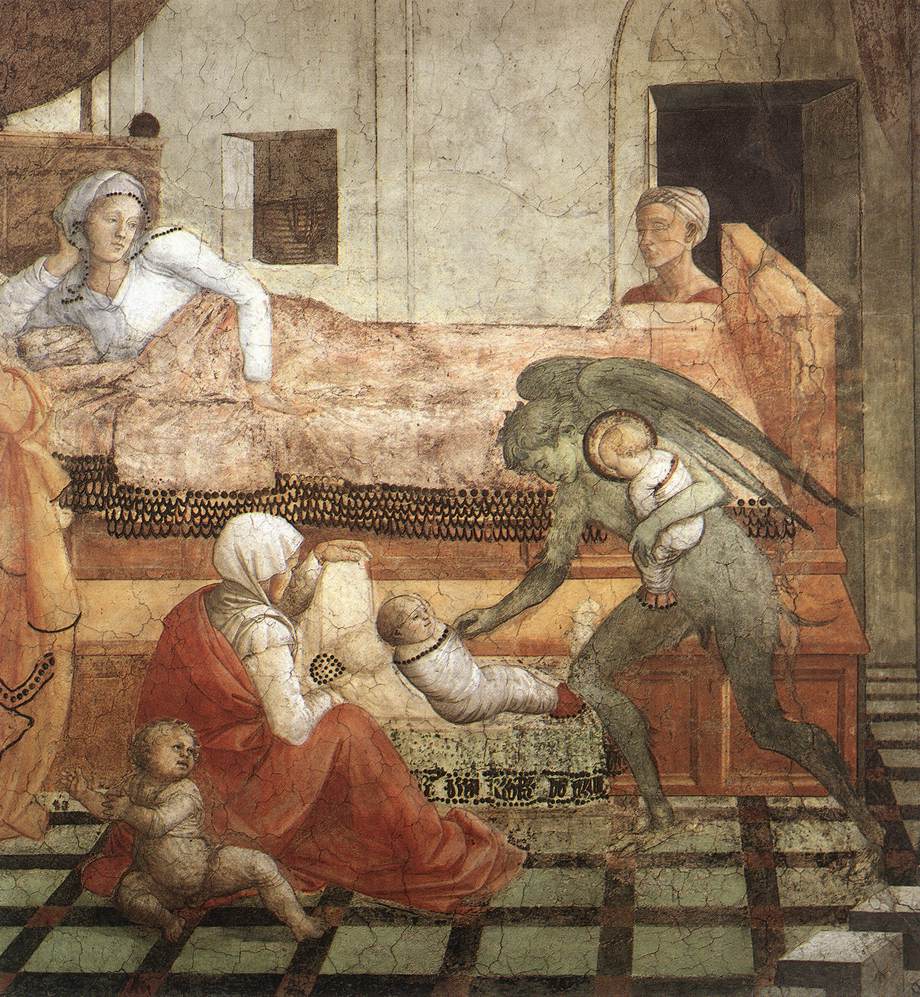

Detail of Disputation in the Synagogue, 1452-65 Detail of St. Stephen is Born and Replaced with Another Child, 1452-65

Detail of St. Stephen is Born and Replaced with Another Child, 1452-65