Saturday, October 10th, 2009

Artist as Thief: Filarete

If I was taught anything about Filarete in school, I don’t remember it. I’ve been reading up on this artist in preparation for an upcoming lecture on self-portraiture. I like that Filarete included portraits of himself and his assistants on one of his best-known works, the bronze doors for St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome (see door on the right of the facade here). This portrait is located on the lowest part of the right valve of the doors, on the back. Filarete identifies himself and his assistants with Latin inscriptions, includes the date of completion (July 30., 1445) and then the statement: “To other artists satisfaction from payment or from pride, but for me – joyfulness.”1

If I was taught anything about Filarete in school, I don’t remember it. I’ve been reading up on this artist in preparation for an upcoming lecture on self-portraiture. I like that Filarete included portraits of himself and his assistants on one of his best-known works, the bronze doors for St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome (see door on the right of the facade here). This portrait is located on the lowest part of the right valve of the doors, on the back. Filarete identifies himself and his assistants with Latin inscriptions, includes the date of completion (July 30., 1445) and then the statement: “To other artists satisfaction from payment or from pride, but for me – joyfulness.”1

Aww, isn’t that cute? Really, Filarete seems like an interesting character. He changed his real name, Antonio di Pietro Averlino, to “Filarete”, which can be translated from Greek as “lover of virtue.”

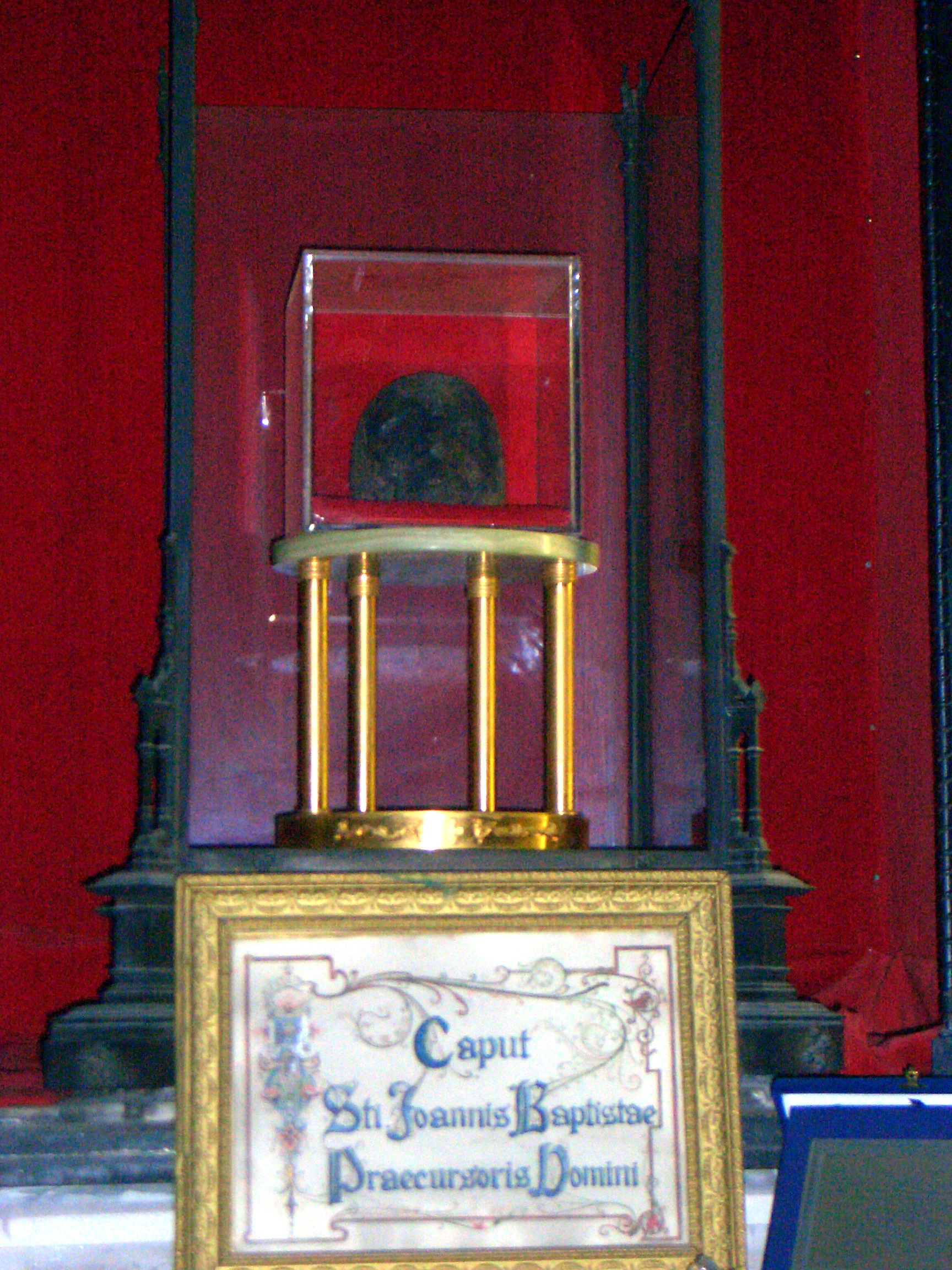

But I have to say, the more I read about Filarete, the more I question how much he loved virtue. The artist was expelled from Rome in 1448, after being accused of stealing some relics.2 And it appears that these weren’t just any relics that Filarete wanted to steal – he tried to steal the head of John the Baptist that used to be located in San Giovanni in Laterano.3 I assume this is the same head that is still in Rome, but is now located in San Silvestro in Capite (shown on the right).

Why anyone want to steal the head of John the Baptist is completely outside my realm of comprehension.

And, by the way, did you know that there are several sites which claim to have the relic of John the Baptist’s head? It’s interesting that John the Baptist was important to multiple religions and groups. Amiens Cathedral (Amiens, France) and the Umayyad Mosque (Damascus, Syria) both claim to have the head, and you can read about a few more places/groups here. There is even a palace/museum, the Munich Residenz, which currently displays the (decorated) heads of John the Baptist and his mother (click here to see a picture of the Baptist display). I don’t know if anyone is counting, but that makes a lot of heads. And I’m pretty sure that John the Baptist only had one head. Maybe the Roman officials should have given Filarete a break; if it is supposed that one of the heads is legitimate, then there is a only a one-in-six chance that Filarete actually stole something valuable.4

1 Emma Barker, Nick Webb, and Kim Woods, eds., The Changing Status of the Artist, (London: Yale University Press, 1999), 63.

2 Evelyn S. Welch, “Art and Authority in Milan,” no. 8846 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 152 (page can be accessed online here).

3 John Pope-Hennessey, Italian Renaissance Sculpture (London: Phaidon, 1958), 332.

4 It’s interesting to add that Mormons would find that none of the heads could be legitimate. They would say that the Baptist’s head is back on the resurrected man’s shoulders (see here).