Wednesday, June 19th, 2013

The Slashing of Velasquez’s “The Rokeby Venus”

Velasquez, "The Toilet of Venus" (also called "The Rokeby Venus), 1648. The National Gallery of Art, London. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Last week I met a feminist scholar who mentioned that she likes to show her students Velasquez’s “The Toilet of Venus” (commonly known as “The Rokeby Venus”) when she takes students to London on a study abroad program. This scholar teaches her students about the suffragette Mary Richardson, who slashed this canvas multiple times in 1914 in order to protest the recent arrest of suffragette leader Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst.

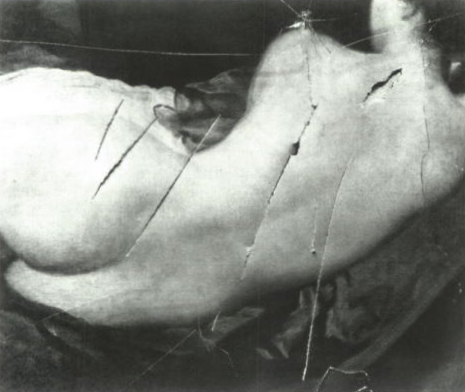

Detail of damage to "The Rokeby Venus." The attack by Mary Richardson occurred in the National Gallery 1914. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

I recently watched a BBC documentary (from “The Private Life of a Masterpiece” series) that covered more details about this attack (beginning about 32:17 in the linked video). At the time, Mary Richardson did not mention that she was bothered by the painting itself. However, Richardson mentioned in 1952 that she was bothered by the subject matter of this painting (as a female nude which attracted the attention of male viewers); this sentiment appropriately encouraged the soon-to-be feminist movement to uphold this attack a symbols of feminist attitudes toward the female nude.1

I think that the image of the slash marks are particularly interesting, because they remind the viewer that the Venus is actually an illusion which is painted on a two-dimensional surface. It’s also interesting to see how the media responded to this attack, since they cast Mary Richardson as a murderer (referring to her as “Slasher Mary,” which is a charged term given that Jack the Ripper killings took place a few decades before). Since Venus was proven to be an illusion instead of an actual body, Richardson had essentially “killed” the Venus.2

It is also interesting that Richardson concentrated her attack on the body of the Venus figure itself, as if to prevent the back and buttocks from serving as palpable, believable fetishes for the male viewer. In its original (now restored) state, this painting is well-construed for fetishization: the back and buttocks are highlighted as objects, especially since the “subjecthood” or “personhood” of the female is lessened through the obscured face (which is not only turned from the viewer, but is represented in the mirror in a very blurry, undefined manner). Richardson’s marks, however, challenge and defy this fetishization.

Do you know of any other physical attacks on works of art by feminists? Do you have any other thoughts on what new meanings were created by Richardson’s slash marks?

1 In 1952, in an interview, Mary Richardson said, “I didn’t like the way men visitors gaped at the painting all day long.” This quote is mentioned in “The Rokeby Venus” episode from “The Private Life of a Masterpiece” BBC series, but also found at “Political Vandalism: Art and Gender” found here: http://www.angryharry.com/rePoliticalVandalism.htm

2 Laura Nead discusses how the media used words that seemed to suggest that wounds were inflicted on an actual body, instead of a pictorial representation of a female. See Lynda Nead, “The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality”. (New York: Routledge, 1992), 2.