Saturday, July 9th, 2011

Strawberries as an "Earthly Delight"

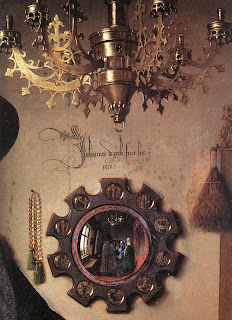

I’ve been thinking about Hieronymous Bosch and The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1510-1515) quite a bit this week. In fact, this afternoon I sat down to write a post about how Bosch’s “tree-man” (located in the center of the panel which depicts Hell) is believed by some to be a self-portrait of the artist.1 But, I’m not going to write on that. At least not right now.

Instead, I’ve become pleasantly distracted by Walter S. Gibson’s article, “The Strawberries of Hieronymous Bosch.” These strawberries appear all over the central panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights altarpiece (see details on right and below). Gibson notes that Bosch’s strawberries garnered attention from viewers very early on. In fact, in 1593 an inventory for some of Philip II’s pictures mentions that the altarpiece had earned the nickname the Madroño (or “the Strawberry”).2 Twelve years later a librarian at El Escorial, Philip’s monastery-palace, explained that the panel is “of the vanity and glory and the passing taste of strawberries or the strawberry plant and its pleasant odor that is hardly remembered once it has passed.”3 This librarian, named Fray José de Sigüenza, felt that the strawberry was the most important feature of Bosch’s garden, and was the fruit was a symbol of the ephemeral, transient nature of earthly pleasures.

Instead, I’ve become pleasantly distracted by Walter S. Gibson’s article, “The Strawberries of Hieronymous Bosch.” These strawberries appear all over the central panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights altarpiece (see details on right and below). Gibson notes that Bosch’s strawberries garnered attention from viewers very early on. In fact, in 1593 an inventory for some of Philip II’s pictures mentions that the altarpiece had earned the nickname the Madroño (or “the Strawberry”).2 Twelve years later a librarian at El Escorial, Philip’s monastery-palace, explained that the panel is “of the vanity and glory and the passing taste of strawberries or the strawberry plant and its pleasant odor that is hardly remembered once it has passed.”3 This librarian, named Fray José de Sigüenza, felt that the strawberry was the most important feature of Bosch’s garden, and was the fruit was a symbol of the ephemeral, transient nature of earthly pleasures.

Many symbolic interpretations for the strawberries have been put forward, and most of them have negative connotations.4 For example, strawberries have multiple seeds, which could hint at promiscuity.5 The other fruit included in the central panel (such as the big raspberries) could also be associated with promiscuity for this same reason.

Many symbolic interpretations for the strawberries have been put forward, and most of them have negative connotations.4 For example, strawberries have multiple seeds, which could hint at promiscuity.5 The other fruit included in the central panel (such as the big raspberries) could also be associated with promiscuity for this same reason.

Gibson suggests that the strawberry imagery might connected to a text by Virgil (which probably would have been familiar to Bosch and Hendrik III because Virgil’s passage is referenced in Roman de la Rose, a popular poem in the Burgundian court). In this text, Virgil warns children to not gather strawberries, because “the cold, evil serpent” is hiding the grass nearby. It seems to me that Bosch’s strawberries could serve as an indirect reference to a serpent (and, by extension, the Fall and sin). Such associations fit well with the imagery for The Garden of Earthly Delights, don’t you think? That being said, I also think that there isn’t just one specific symbolic meaning for these strawberries. Since this altarpiece undoubtedly served as a focus for intellectual discussion, it is appropriate that Bosch used imagery that was replete with symbolic associations.

Do you know of any other interpretations for the strawberries in this altarpiece? Do you know of any works of art which also include strawberries for symbolic reasons? On a fun side note, I found an amusing comparison between Katy Perry and Bosch’s fruit here. No doubt that Perry would view Bosch’s strawberries as a symbol of sexuality!

Do you know of any other interpretations for the strawberries in this altarpiece? Do you know of any works of art which also include strawberries for symbolic reasons? On a fun side note, I found an amusing comparison between Katy Perry and Bosch’s fruit here. No doubt that Perry would view Bosch’s strawberries as a symbol of sexuality!

1 David G. Wilkins, Bernard Schultz, Katheryn M. Linduff, Art Past Art Present, 6th edition, (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2009), 327.

2 Walter S. Gibson, “The Strawberries of Hieronymous Bosch,” in Cleveland Studies in the History of Art 8 (2003): 25.

3 Ibid.

4 There are some positive interpretations of the strawberry which exist. In fact, Gibson points out that the strawberry was seen a medieval symbol of the Virgin. Such exalted associations with the fruit have led a handful of individuals to interpret Bosch’s central panel as a scene of transcendent bliss and spiritual love. For a brief synopsis of these interpretations, see Gibson, 26-27.

5 Wilkins, 326.