Wednesday, December 9th, 2009

My cousin just sent me this post, and I’m so excited/jealous about the news that I have to post right away. The story sounds like a dream-come-true: an Italian couple decided to remodel their apartment and found a 16th century fresco behind their plastered wall! Although Tarcisio and Teresa de Paolis found the fresco in the 1970s, they only recently decided to announce their find to the public (it appears they were worried that they would lose their home because of this discovery).

My cousin just sent me this post, and I’m so excited/jealous about the news that I have to post right away. The story sounds like a dream-come-true: an Italian couple decided to remodel their apartment and found a 16th century fresco behind their plastered wall! Although Tarcisio and Teresa de Paolis found the fresco in the 1970s, they only recently decided to announce their find to the public (it appears they were worried that they would lose their home because of this discovery).

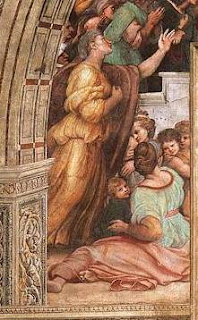

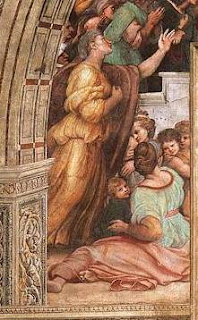

The fresco appears to be by Ugo da Scarpi – it is a miniaturized copy of frescoes from Raphael’s “

Room of Heliodorus” (1512-1514; located in the Vatican – you can take a

virtual tour of the room here). The detail on the right is from Raphael’s fresco

The Mass at Bolsena; you can compare this detail with the da Scarpi copy (located in the photograph with the de Paolis couple).

What an amazing find! I’m green with envy. I have a secret hope that one day I’ll discover a masterpiece that was hidden away in an attic or antique shop.

Do you know of any other amazing art discoveries?

Monday, December 7th, 2009

I’m in a state of shock. Vasari is best known as the biographer for the great (male) artists of the Italian Renaissance – Michelangelo, Donatello, Raphael, Leonardo, etc. But did you know that Vasari mentioned four females in his Lives of the Artists? I had no idea, until I discovered Vasari’s chapter on Properzia de’Rossi the other night. I seriously was dumbfounded – I stared at the word “sculptress” for at least ten seconds.

But don’t get too excited, my feminist art historian friends. Vasari only mentions Rossi in a few paragraphs, and then taps on a few short sentences about three other female artists: Sister Plautilla, Madonna Lucrezia, and Sofonisba Anguissola. You’ve never heard of these artists, you say? Let me show you a sampling of their work:

On the right is Properzia de’Rossi’s

Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife (1520s). Vasari mentions that the subject matter of this panel can parallel the unrequited love that Rossi experienced in her own life. I think this comparison is telling about Vasari’s views on women and feminine nature. The editor of my

Lives edition also echoed my thoughts, saying that “while male artists execute works without regard to their personal feelings throughout the

Lives, Vasari seems unable to imagine a woman creating a work of art without sentimental or romantic inspiration.”

1

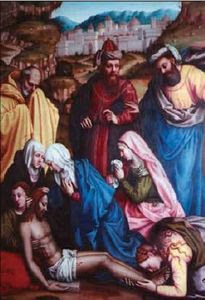

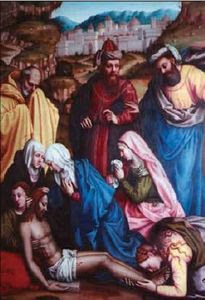

On the left is Lamentation with Saints (16th century) by Sister Plautilla (Plautilla Nelli). Vasari mentions that Plautilla was an extremely prolific painter, but surprisingly (or perhaps not-so-surprisingly), only three works are definitively attributed to her today. In an effort to bring public awareness to this artist, the Florence Committee of National Museum Women in the Arts paid to have Lamentation restored in 2006 (see news article here).

On the left is Lamentation with Saints (16th century) by Sister Plautilla (Plautilla Nelli). Vasari mentions that Plautilla was an extremely prolific painter, but surprisingly (or perhaps not-so-surprisingly), only three works are definitively attributed to her today. In an effort to bring public awareness to this artist, the Florence Committee of National Museum Women in the Arts paid to have Lamentation restored in 2006 (see news article here).

I think it’s especially interesting that Vasari doesn’t make any statements about Plautilla’s divine role as an artist or God-given talent (which he makes about the male artists in his book). Instead, he stresses that Plautilla and the other ]female artists learned and acquired artistic skill. Futhermore, Vasari wrote this about Plautilla: “But best among her works are those she imitated from others, which demonstrates that she would have created marvellous works if, like men, she had been able to study and work on design and draw natural objects from life.”2 Plautilla was alive when Vasari wrote her biography, and I wonder if she cringed to know that Vasari thought her best works were those that she copied from the divinely inspired, male artists.

Sofonisba Anguissola is the only female artist with whom I was familiar before reading Vasari. I read about Anguissola when I was doing research on Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard. Several scholars think that Caravaggio’s two versions of this subject were influenced by Anguissola’s Boy Bitten by a Crayfish (also called Boy Bitten by a Crab, c. 1554, on right). Mary Garrard has discussed Anguissola’s drawing in depth. She mentioned how Anguissola painted a picture of a laughing girls, which Michelangelo saw and commented that “the image of a crying boy would have been better.”3 Garrard finds that Michelangelo’s statement implied that boys are better artistic subjects than girls, and tragedy is better than comedy.4 Upon hearing this, Anguissola sent Michelangelo the drawing of Boy Bitten by a Crayfish. However, instead of showing the crying male in a tragic, noble position (and follow Michelangelo’s inferred suggestion), Anguissola shows the boy in an ignoble state with an amused female standing nearby. Wasn’t Anguissola a little sassy? I wonder what Michelangelo thought of the drawing.

Sofonisba Anguissola is the only female artist with whom I was familiar before reading Vasari. I read about Anguissola when I was doing research on Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard. Several scholars think that Caravaggio’s two versions of this subject were influenced by Anguissola’s Boy Bitten by a Crayfish (also called Boy Bitten by a Crab, c. 1554, on right). Mary Garrard has discussed Anguissola’s drawing in depth. She mentioned how Anguissola painted a picture of a laughing girls, which Michelangelo saw and commented that “the image of a crying boy would have been better.”3 Garrard finds that Michelangelo’s statement implied that boys are better artistic subjects than girls, and tragedy is better than comedy.4 Upon hearing this, Anguissola sent Michelangelo the drawing of Boy Bitten by a Crayfish. However, instead of showing the crying male in a tragic, noble position (and follow Michelangelo’s inferred suggestion), Anguissola shows the boy in an ignoble state with an amused female standing nearby. Wasn’t Anguissola a little sassy? I wonder what Michelangelo thought of the drawing.

Madonna Lucrezia is the other female artist mentioned by Vasari. Unfortunately, there isn’t any (known) surviving art by her. In fact, we know little about Lucrezia beyond that she was active around 1560 and her teacher was Alessandro Allori. It’s sad to think that her work and life is lost to history, most likely because she was a female. I’m glad that Vasari made the effort to mention her and these other females in his Lives, but also disappointed that most females didn’t receive artistic opportunity or art historical attention at the time. It makes me wonder what other female artists have been unappreciated and obscured by historical biases.

Is anyone else shocked that Vasari mentioned female artists in his text?

1 Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, translation by Julia Conway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (London: Oxford University Press, 1991), 565.

2 Ibid., 342.

3 Mary D. Garrard, “Here’s Looking at Me: Sofonisba Anguissola and the Problem of the Woman Artist,” Renaissance Quarterly 47, no. 3 (Autumn, 1994): 611.

4 Ibid., 612.

Monday, November 2nd, 2009

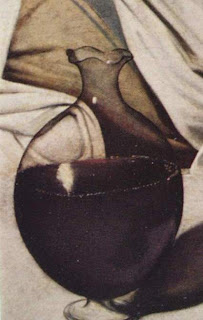

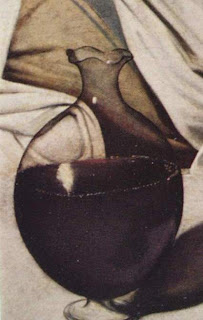

If I asked you what was in this detail of Caravaggio’s Bacchus (1597), and you answered “A carafe of wine,” you would only be given partial-credit for your answer. Sorry. This detail, my friends, has been found to contain an early self-portrait of Caravaggio at his easel, shown as a reflection in the glass carafe.

You’re aren’t seeing it, you say? To tell you the truth, me neither. In actuality, you can’t see this detail with the naked eye. It used to be visible, however, since it was mentioned by an Italian restorer in 1922. However, poor restoration efforts and the gradual darkening of this image have obscured this small portrait over time. Only recently did the portrait “resurface” through reflectography, and the image results were revealed last Friday at a conference in Florence.

You can kinda-sorta see the portrait of Caravaggio in

this Telegraph article, which posted the reflectography results and circled where the portrait is located. I’m still not seeing too much, but I’m trusting that one can actually see a young Caravaggio, paintbrush in hand, with his arm extended toward a canvas on an easel.

Pretty cool, huh? I wonder if restorative efforts can make this self-portrait visible again to the naked eye.

Tuesday, October 27th, 2009

In an ideal world, I would have time to blog about whatever strikes my fancy. (Really, in an ideal world, I would get paid to blog about whatever strikes me fancy.) There are a couple of major events that have happened recently in the art world, but I haven’t had time to write about them (mostly because I get distracted by silly things like Giovanni Arnolfini’s red turban). Here are two news items that I’ve wanted to blog about, but haven’t had the chance:

In an ideal world, I would have time to blog about whatever strikes my fancy. (Really, in an ideal world, I would get paid to blog about whatever strikes me fancy.) There are a couple of major events that have happened recently in the art world, but I haven’t had time to write about them (mostly because I get distracted by silly things like Giovanni Arnolfini’s red turban). Here are two news items that I’ve wanted to blog about, but haven’t had the chance:

– The recent attribution of a Leonardo da Vinci painting via fingerprinting (shown above). You can read about the story here and see a BBC video clip here. Heidenkind expressed some of her reservations about this new attribution, and I kind of feel the same way. I’m not sure if I’m ready to jump on the “La Bella Principessa” bandwagon yet.

– Earlier this month Egypt cut off ties with the Louvre due to an ownership dispute regarding antiquities. In order to maintain good relations, the Louvre quickly agreed to return five fresco fragments to Egypt.

I like to keep up-to-date with major/interesting art news on this blog, but I realize that it’s not feasible to write about everything (especially since I tend to get distracted and write about whatever I’m thinking about/researching). So, I’ve decided to start a Twitter account for Alberti’s Window. Please follow me. You also may have noticed that I’ve also uploaded a “tweet feed” on the left side of the blog page. I’ll tweet about interesting art news, short art history thoughts, and one-liner reviews of art exhibitions. It should be fun!

Friday, October 23rd, 2009

My friend rachsticle just got back from a trip to China. I am really, REALLY jealous that she got to see the terracotta warriors at Xi’an. These warriors are placed to protect the tomb of the emperor Qin Shi Hugandi, who proclaimed to be the first emperor of China in 221 BC.

My friend rachsticle just got back from a trip to China. I am really, REALLY jealous that she got to see the terracotta warriors at Xi’an. These warriors are placed to protect the tomb of the emperor Qin Shi Hugandi, who proclaimed to be the first emperor of China in 221 BC.

So, what’s the big deal about these warriors? Well, first off, it’s estimated that there are about TEN THOUSAND of them. These warriors were discovered in 1974, and over the past thirty-five years only about an eighth of the warriors have been excavated. Some of these underground vaults and pits are very hard to access (there are around 600 pits that cover a 22 square-mile area), but excavations are still in progress.

Huangdi arranged a mass-production project to create all of these warriors. Almost in assembly line fashion, artisans cranked out bodies and then customized them with ears, mustaches, hats, shoes, etc. Many of the figures appear strikingly individualized, but it’s not likely that they were modeled after real people. Instead, it’s more probable that the workers were instructed to represent different regional types of Chinese people.

If you don’t have plans to go to China soon, you could still see some of these statues in Washington DC. Next month, terracotta warriors will be on display in the National Geographic Society Museum, as part of an exhibition series which features the largest collection of these statues to ever leave China. You can read more about these statues and the upcoming exhibition in this Smithsonian article.

Sadly, I don’t have plans to go to China or DC in the near future. If you’re like me, then feel free to content yourself with some of rachsticle’s pictures (thanks, friend!):

It appears that the artisans had different molds for body types.

Look at how some of the bodies are skinnier than others.

My cousin just sent me this post, and I’m so excited/jealous about the news that I have to post right away. The story sounds like a dream-come-true: an Italian couple decided to remodel their apartment and found a 16th century fresco behind their plastered wall! Although Tarcisio and Teresa de Paolis found the fresco in the 1970s, they only recently decided to announce their find to the public (it appears they were worried that they would lose their home because of this discovery).

My cousin just sent me this post, and I’m so excited/jealous about the news that I have to post right away. The story sounds like a dream-come-true: an Italian couple decided to remodel their apartment and found a 16th century fresco behind their plastered wall! Although Tarcisio and Teresa de Paolis found the fresco in the 1970s, they only recently decided to announce their find to the public (it appears they were worried that they would lose their home because of this discovery). The fresco appears to be by Ugo da Scarpi – it is a miniaturized copy of frescoes from Raphael’s “Room of Heliodorus” (1512-1514; located in the Vatican – you can take a virtual tour of the room here). The detail on the right is from Raphael’s fresco The Mass at Bolsena; you can compare this detail with the da Scarpi copy (located in the photograph with the de Paolis couple).

The fresco appears to be by Ugo da Scarpi – it is a miniaturized copy of frescoes from Raphael’s “Room of Heliodorus” (1512-1514; located in the Vatican – you can take a virtual tour of the room here). The detail on the right is from Raphael’s fresco The Mass at Bolsena; you can compare this detail with the da Scarpi copy (located in the photograph with the de Paolis couple).